Flirting With IDA and APT28

This document shares a methodology used to develop Hex-Rays' Interactive Disassembler (IDA) signatures created as part of pre-analysis for a recently published APT28 sample. The internal functions, features and behavior of the published sample are not discussed. Access to IDA Flair, used to generate signatures for the IDA disassembler, requires a current hex-rays subscription.

On May 17, the U.S. CyberCom Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF) tweeted a VirusTotal link to a new APT28 malware sample. No information about the circumstances surrounding the sample or its discovery was included.

The SHA256 hash of the published sample is:

b40909ac0b70b7bd82465dfc7761a6b4e0df55b894dd42290e3f72cb4280fa44

Consensus amongst researchers suggests the sample is x-tunnel (aka XAPS), a tool used by APT28 to make a compromised host inside the firewall act as a traffic proxy. This allows attacker-controlled traffic originating from external hosts to be relayed to other internal targets that might otherwise be inaccessible owing to perimeter traffic policy.

X-tunnel was first seen in the wild in May 2013, and is understood to have been used in previous compromises including the 2016 DNC hack.

Analysis of other in-the-wild (ITW) builds of x-tunnel shows its capabilities include remote command execution, UDP tunnelling, TLS encryption, proxy support, and persistent HTTP via the HTTP keep-alive header.

Prior versions have weighed in around 1-2MB in size. Versions with obfuscated code, found in 2015, tended towards the larger end of the scale. The sample uploaded by CNMF stands at 3.2MB.

A file this size hints at code obfuscation/virtualisation, static linking and/or embedded resources. Static linking affords self-sufficiency - a high priority for a threat actor operating inside a victim network. Code obfuscation hampers analysis efforts but can make a sample more suspicious in the eyes of antivirus (AV) software.

Evidence within the sample indicates it was produced using Microsoft Visual C++. When

formulating an execution plan for a target computer, the author has two options: assume the corresponding (and necessary) Visual C++ Redistributable package is installed, or bundle (link) every piece of executable code needed within the file itself. This latter approach of static linking increases the size of the file but also increases the odds of successful execution.

A few hints that our x-tunnel binary was built with Microsoft Visual C++:

1. The presence of a .pdata section containing the exception data directory. It’s here that the compiler stores exception handling metadata for PE32+/64-bit binaries. This section is present even for the simplest C/C++ ”Hello World” applications, provided it links against Microsoft Visual C++ Runtime.

2. For C++ specifically, the presence of mangled function names and references to Standard Template Library namespaces/containers/classes (“std”, “vector”, “ios”) within the strings output.

3. Output from parsing the PE Rich header.

For the alternative of dynamic linking a Visual C++ PE, you would typically see an import for mscvpXXX.dll, where XXX maps to the Visual Studio release number – 120 for Visual Studio 2013, 140 for Visual Studio 2015 etc.

Disassembly of the sample using IDA shows a vast sea of executable code. What approach can we use to tackle the analysis of such an unwieldy file, allowing us to quickly zero in on its design and capabilities?

IDA’s Navigator toolbar offers a visual decomposition of a sample’s executable code and data. If, during sample loading, the automatic use of Flirt Signatures is disabled (see “Kernel Options 2”), measuring the number of functions can be achieved using a simple Python one-liner:

|

Figure 1: Function count via IDAPython

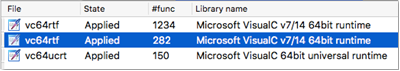

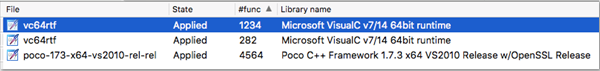

Since we’re dealing with a 64-bit Microsoft Visual C++ binary, we can apply the relevant default signatures provided with IDA (first re-select Use flirt signatures under General -> Kernel Options 2): vc64rtf, vc64ucrt.

The Signatures sub-view tells us ~1600 functions have been identified as library (benign) code:

Figure 2: First round of default signatures provided by IDA

The majority of published x-tunnel samples link against the same version of the OpenSSL TLS/SSL library. Strings output for this sample shows it is also following suit: 1.0.1e 11 Feb 2013.

Analysts following along at home will also have noticed another recurring identifier present in the strings output: “poco”. Google results show this to be a C++ framework. In the ongoing effort to stay ahead of endpoint security, the author(s) have evidently re-tooled x-tunnel using a framework.

Leveraging custom IDA Flirt signatures to fill in as many of the blanks as possible (by identifying benign library code) reduces the time required to derive meaningful analysis of the sample. Focusing our efforts on understanding the important (interesting) parts means we can expedite delivery of actionable threat intelligence.

Strings output tell us version 1.7.3 of the Poco framework was used. We can use this information to build a static library (.lib) and from that, derive custom IDA signatures.

Note: The Flair tools pcf (COFF parser) and sigmake (Signature File Maker) are available from the Hex Rays website as a zip download (active subscription required). Both Mac and Windows binaries are included; substitute paths in examples below reflect the location of your zip extract (and operating system, if using Windows).

The first question we need to answer is which version of Visual Studio should we use to build our libs, and for the sake of curiosity, does it matter? (Spoiler: yes it does, at least for the small number of default installs of Visual Studio that were tested).

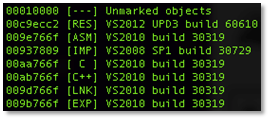

The Rich header in the PE holds metadata about the compiler/linker used to produce a binary. Parsing it using one of the widely available tools we are shown:

Figure 3: Rich header embedded within the sample

Assuming this isn’t a forgery, our first build attempt should be with Visual Studio 2010 RTM.

Note: Building the OpenSSL and Poco static libraries was performed using the author’s standard Windows 7 SP1 x86 analysis environment. Building under a native x64 environment should only involve minor changes to the steps described below.

The Poco framework’s 1.7.3 source code is readily available for download from Github. The build instructions are easy to follow (see README, “Building on Windows”). The only minor caveat is a dependency on OpenSSL, which needs to exist first. We will adjust the build process slightly to remove the MySQL dependency. This can be done by editing the Poco components file.

Building the OpenSSL .lib files is also straightforward. As stated by the documentation, some prerequisites need to be installed such as ActiveState ActivePerl; make sure perl.exe is in your %PATH% (handled by the installer when using defaults).

Since our sample is 64-bit, we use the Visual Studio x64 Cross Tools Command Prompt (see Windows Start menu under Visual Studio Tools).

As per the OpenSSL build documentation, running the following commands in the extracted source code directory should produce the necessary libeay32.lib and ssleay32.lib static libraries. This, in turn, will allow us to build Poco and finally produce our IDA signatures:

| perl Configure VC-WIN64A ms\do_win64 anmake -f ms\nt.mak |

Figure 4: Building OpenSSL static libs

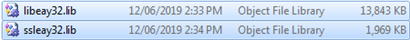

Assuming the build process completes without error, static libraries should be in the out32 folder:

Figure 5: OpenSSL x64 1.0.1e static libraries

With these available, we can now build the Poco C++ framework libs. We need to modify the Poco buildwin.cmd file to indicate the location of our freshly built OpenSSL libraries and provide the whereabouts of OpenSSL header files. Here’s the edited buildwin.cmd:

| rem Change OPENSSL_DIR to match your setup set OPENSSL_DIR=E:\Code\openssl-1.0.1e.tar\openssl-1.0.1e set OPENSSL_INCLUDE=%OPENSSL_DIR%\inc32 set OPENSSL_LIB=%OPENSSL_DIR%\out32dll;%OPENSSL_DIR%\lib\VC set INCLUDE=%INCLUDE%;%OPENSSL_INCLUDE% set LIB=%LIB%;%OPENSSL_LIB% |

Figure 6: Poco framework buildwin.cmd environment variables

Note the use of inc32 for the OPENSSL_INCLUDE variable. The 1.0.1e tarball contains symlinks from include to inc32 that fail to extract properly on a Windows host, resulting in 0 byte .h files in the include folder.

We can now build the Poco framework static libs using the Visual Studio 2010 x64 command prompt:

|

Figure 7: Command to build Poco static libs

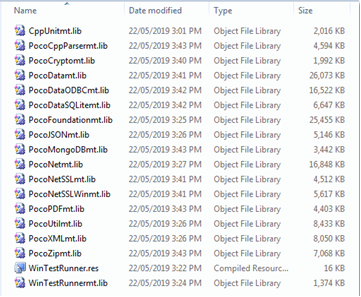

The emitted libs can be found in the lib64 folder:

Figure 8: Poco framework static libraries

Armed with our Poco and OpenSSL library files, we can now generate the IDA signatures.

The syntax for pcf and sigmake is straightforward. First, derive a pattern file for each of our .libs using pcf, found inside the Flair .zip download, available from Hex-Rays.

An example execution of pcf for the OpenSSL libs on Mac OS (the .libs were copied locally from the build VM):

| ./flair72/bin/mac/pcf libeay32.lib libeay32.lib: skipped 98, total 5646 |

Figure 9: Generating the IDA pattern file on MAC

For Windows, an equivalent command would be:

|

Figure 10: Generating the IDA pattern file on Windows

Now generate signature files and resolve any resulting collisions. Collisions occur when the generalized opcodes taken from object files within the .lib are the same for more than one sub routine. The Flair signature generator won’t arbitrate, it’s up to the user to hand-curate (or ignore) any collisions.

Depending on how many collisions are identified and how much time is available, you can opt to leave all colliding subroutines un-named or manually resolve/assign names by inspecting the .exc file.

It’s helpful to add a name field to the signature file. This will be displayed in the FLAIR selection dialog, making your custom sigs easier to identify – particularly if you’re building lots of different versions with distinct compiler flags:

| ./flair72/bin/mac/sigmake -n"OpenSSL 1.0.1e x64 VS2010 LIBEAY32 Od" libeay32.pat openssl-101e-x64-vs2010-libeay32.sig openssl-101e-x64-vs2010-libeay32-Od.sig: modules/leaves: 2971/5438, COLLISIONS: 114 |

Figure 11: FLAIR signature creation command-line

For this example, we opt to take the path of least resistance and ignore all collisions - delete the four comment lines at the top of the generated .exc file. Re-execute sigmake to indicate the contents of the .exc file should be incorporated. No output means success. Repeat for ssleay32.lib.

As a final step, our signatures need to be copied into the IDA install. On Mac OS for PE/COFF files:

|

Figure 12: IDA signature files location on MAC

For Windows installs, the default location would be:

|

Figure 13: IDA signature files location on Windows

With the signatures in place, let’s apply them to the sample (File -> Load File -> FLIRT Signature File). No IDA restart is required.

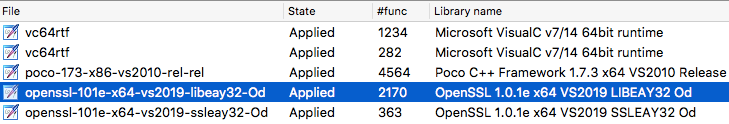

The Signatures sub-view tells us how well our signatures are faring:

Figure 14: Poco framework signatures applied

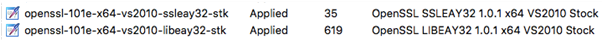

Complementing this with our OpenSSL signatures:

Figure 15: OpenSSL signatures applied

Progress, but many OpenSSL functions have been missed. Skimming through the disassembly for code still flagged as Regular function, the string annotations (comments) for OpenSSL code are readily apparent. Something in our signature generation has run wide of the mark.

By cross-referencing disassembly strings in IDA (e.g., “retcode=” present in sub_180097950), with the OpenSSL source code (hint: grep), we can identify a routine to serve as a starting point for improving our custom signatures.

For the sake of brevity, sub_180097950 in IDA is the OpenSSL function module_run, found in ./crypto/conf/conf_mod.c. The string constants to the ERR_add_error_data function map (uniquely) to the IDA-generated cross-reference comments.

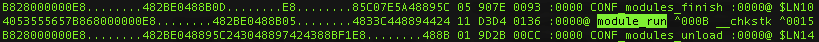

Inspecting libeay32.pat gives us the current pattern is for the module_run function:

Figure 16: FLAIR pattern for module_run

Which disassembles to:

Figure 17: OpenSSL’s module_run as compiled using “Ox” in Visual Studio 2010

Compare this with our sample’s module_run:

Figure 18: sub_180097950 opcodes

Clearly, our .lib compiled with Visual Studio 2010 has generated a different set of opcodes.

If object files inside the .lib have differing opcodes, then our derived signatures won’t match those in the sample and, as is the case for our “stock” build here, legitimate OpenSSL code is missed.

The disassembly for the module_run opcodes in our .pat file starts with a 2-byte hotpatch aligned[1] push rbx instruction (40 53; hotpatch is implicit on x64). This is followed by preservation by the callee of non-volatile registers rbx, rsi, rdi, as determined by the x64 calling convention.

Our APT-28 function prolog for the same function shows the use of spill or home space on the stack for the r8, r9, rcx and rdx registers.

An explanation for the difference in compiler output comes courtesy of Raymond Chen in a blog post from 2011:[2]

"When compiler optimizations are disabled, the Visual C++ x64 compiler will spill all register parameters into their corresponding slots. This has as a nice side effect that debugging is a little easier, but really it’s just because you disabled optimizations, so the compiler generates simple, straightforward code, making no attempts to be clever.”

With this in mind, let’s try building a non-optimised version of OpenSSL and see if it yields any improvements to our IDA signature hit count.

OpenSSL compilation is adjusted by modifying nt.mak and editing the CFLAGS statement. Compiler optimisations are disabled by changing the default Ox (most speed optimisations) to Od (disable optimisations):

| # Set your compiler options PLATFORM=VC-WIN64A CC=cl CFLAGS= /MT /Od -DOPENSSL_THREADS -DDSO_WIN32 -W3 –Gs0 -Gy -nologo APP_CFLAG= /Zi /Fd$(TMP_D)/app LIB_FLAG= /Zl /Zi /Fd$(TMP_D)/lib |

Figure 19: Optimisations disabled via Ox -> Od

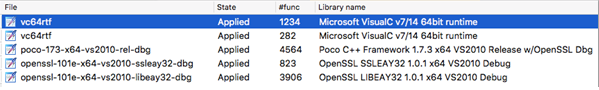

Following recompilation, regeneration of signatures, and a re-apply in IDA, our custom signature hit count looks healthier. The previously missed OpenSSL module_run function has also been correctly identified:

Figure 20: Revised Poco and OpenSSL signatures

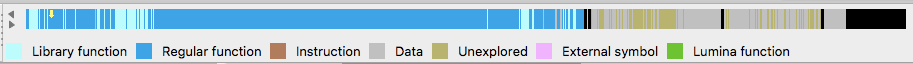

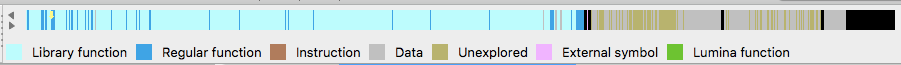

Compare the IDA Navigator toolbar showing initial decomposition (Figure 21) with custom Poco and non-optimised OpenSSL signatures applied (Figure 22):

Figure 21: Initial decomposition

Figure 22: Decomposition after applying Poco and OpenSSL signatures

Much of the remaining, unidentified code relates to C++ exception handling, thunk functions (single jmp instructions), or small sub routines that were marked as having collisions at the time of signature generation. These are easy to identify with only a cursory review.

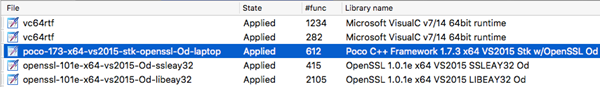

A valid consideration when developing custom signatures is the ability to mirror the author’s development environment. Visual Studio 2010 is quite old and only available for download from Microsoft if you are fortunate enough to have an MSDN subscription. Does the accuracy of our signatures change if Visual Studio 2019 Community Edition is used?

Version 1.7.3 of the Poco C++ framework, released in May 2016, only supports up to Visual Studio 2015, therefore, no attempt was made to rebuild signatures using Visual Studio 2019:

Figure 23: OpenSSL built with VS2019 Community; optimizations disabled

Building v1.0.1e of the OpenSSL framework, released Feb 2013, using Visual Studio 2019 ends in premature failure: unresolved symbols to iob_func,a consequence of stdio changes made to the Microsoft CRT in Visual Studio 2015. Fortunately, the errors occur when building OpenSSL test executables - the static libraries are already (successfully) built by that point.

Repeating the process using Visual Studio 2015 Community Edition:

Figure 24: OpenSSL & Poco Framework built with Visual Studio 2015 Community

For Visual Studio 2015 and 2019, the OpenSSL and Poco static libraries were built following a default install. The reason behind the reduction in signature hits was not investigated. One possibility is the addition of security/SDL checks incorporated by default in newer Visual Studio versions, altering the prolog opcodes and resultant Flair pattern.

Signature hit counts reported by IDA for different Visual Studio builds (2010, 2015 and 2019) tells us the most accurate signatures are obtained when mirroring the author’s build environment – at least for analysis of x64 PE files and when using default installs of Visual Studio.

In this instance, the PE Rich header appears to be telling the truth.

With our custom signatures applied, we’re ready to commence analysis of the sample. Reducing the amount of unidentified code has greatly simplified the analysis effort. We can now start in earnest to understand its inner workings, and how this version has evolved from previous ITW variants.

Now the interesting work begins. счастливой охоты!

Lumina metadata for the Poco and OpenSSL libraries has been pushed to Hex Rays. Anyone with IDA 7.2 or above can perform a Lumina pull from within IDA and get immediate identification of all benign library code found within this sample.

Citations:

[1] https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/reference/hotpatch-create-hotpatchable-image?view=vs-2019

[2] https://devblogs.microsoft.com/oldnewthing/20110302-00/?p=11333