Threat Thursday: BlackGuard Infostealer Rises from Russian Underground Markets

BlackGuard is one of the latest .NET-based information-stealers to rise to prominence in Russian underground markets. Though not as broad in functionality as other infostealers, BlackGuard’s focus is on web browsers, cryptocurrency services, and “cold wallets” – crypto wallets that store assets offline for greater security.

BlackGuard has specific functions to extract critical information from a victim's device, similar to both Arkei and Bhunt Scavenger. Additionally, the malware will target VPN clients, instant messaging services, FTP clients and VoIP services.

Following a growing trend for modern malware, BlackGuard is sold and distributed as Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS). The threat group behind the malware offers both monthly subscriptions and a lifetime pass to use the malware. (For “lifetime,” read “until the malware authors get caught.”)

While BlackGuard was first observed by researchers at ZScaler, our analysts took a deeper dive to plumb its depths, and in so doing discovered some functions not previously described, including the malware’s features for evaluating high-value targets, and default browser checks. This blog also includes exclusive screenshots taken from the threat actor’s original sales thread.

Operating System

Risk & Impact

Technical Analysis

BlackGuard infostealer fits neatly into the space a few older, discontinued threats have left behind. It provides a degree of obfuscation that other malware authors often charge a sizeable add-on fee for, all included at a relatively cheap price. The threat also offers ease of use, as well as ease of procurement, as it’s sold on a variety of different forums.

Anti-Analysis Checks

On execution, BlackGuard conducts anti-analysis and anti-detection checks to determine if the malware is being run inside a sandbox or on a device with a specific type of antivirus software installed. If the malware detects the presence of any of the Dynamic-Link Library (.DLL) files listed in the following table, it will attempt to terminate itself, to prevent execution and subsequent detection.

DLL Name

|

Application Name

|

SbieDll.dll

|

Sandboxie Sandbox

|

SxIn.dll

|

360 Total Security

|

Sf2.dll

|

Avast Antivirus

|

snxhk.dll

|

Avast Antivirus

|

cmdvrt32.dll

|

COMODO Internet Security

|

BlackGuard will also query "IP-Whois" to determine the approximate location of the victim. In some samples of BlackGuard, this function is used to prevent the malware’s execution in specific Eastern European nations, which would appear to confirm suspicions regarding where the malware authors are located.

In the samples we analyzed, the malware will stop executing if the victim is based in the following countries:

String Obfuscation

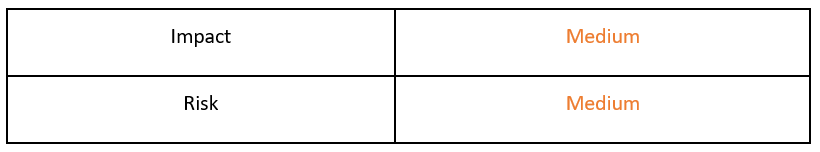

BlackGuard is built using the .NET programming language, which is easily human-readable. To foil this transparency, it makes use of the .NET obfuscator, "Obfuscar.” This technique is often used in malware – and in legitimate software development to prevent unauthorized analysis that might lead to things like cracking and piracy – as an obfuscator makes the source code of a program harder for a human reader to understand.

Obfuscar aggregates all of BlackGuard’s string data into a byte array, and then it XORs the data to prevent the strings from being visible during static analysis. The XOR cipher is a simple additive cipher often used in cryptography.

The byte array is then de-obfuscated at run-time. All original string references are replaced by function calls that use an index and a length to pull the appropriate string out of the byte array. This action is displayed below in Figure 1.

In some cases, the strings are also Base64-encoded and therefore need to be decoded after being retrieved from the byte array. It’s possible that this has been done specifically for the strings that are more obviously indicative of suspicious activity.

These strings contain some of the key malicious functions of the malware, and likely have this additional layer of obfuscation added so the decoded version of the strings do not exist in memory for very long. This additional level of obfuscation makes it less likely for the malicious activity to be picked up by memory scanners and other detection-based antivirus systems.

Figure 1: Breakdown of string de-obfuscation

Information Stealing

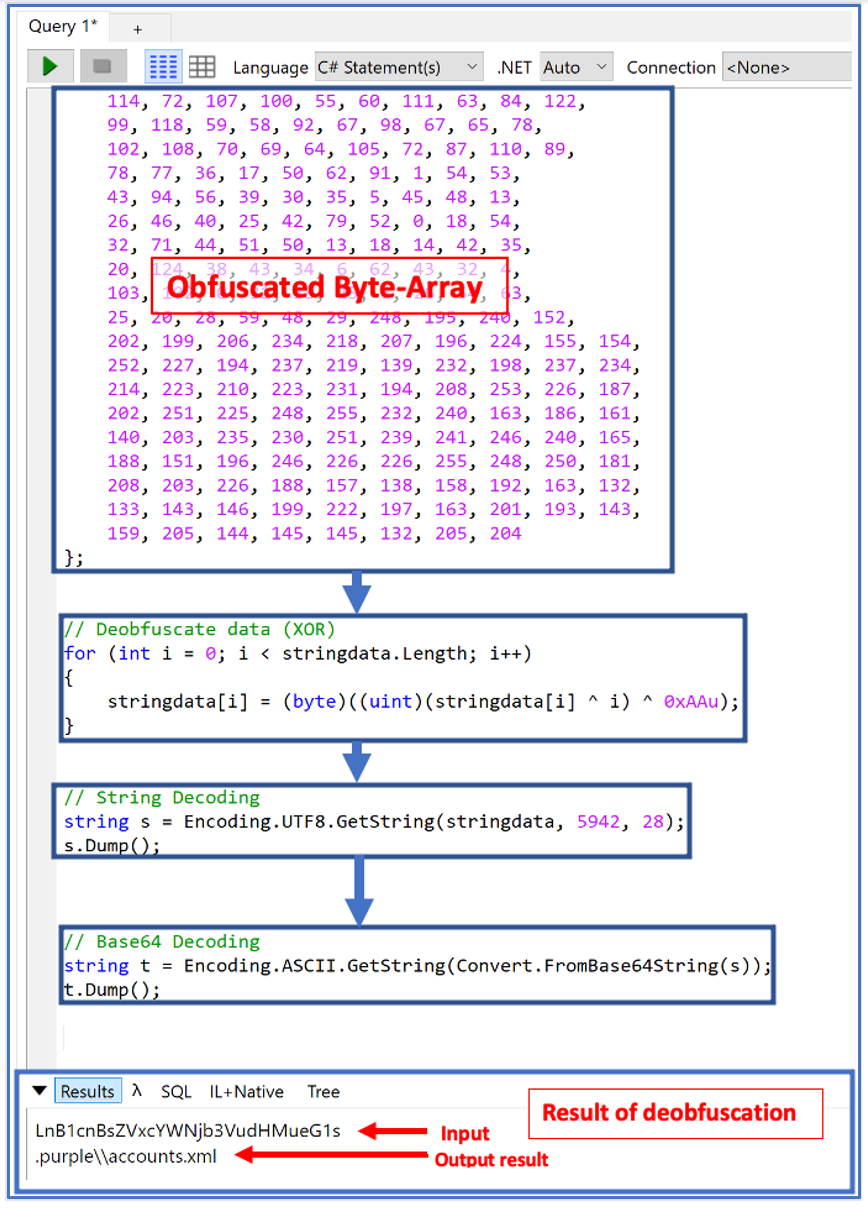

Once all the anti-analysis checks are complete, BlackGuard will create a folder in %AppData% to store its stolen information.

After it has created this folder, BlackGuard starts its information-stealer functionality. The malware is designed to have different functions carry out various goals of information theft, as shown in Figure 2 below. Once decoded, each function can be then mapped to a specific goal the threat actor wants to achieve.

Figure 2 - Breakdown of core infostealer functions

VPNs

BlackGuard will seek out the presence of two popular Virtual Private Networking (VPN) applications, OpenVPN and NordVPN. The threat searches for both applications by looking for their common installation path. It then searches for the username and password in the user data of both applications.

Victim Device Information

BlackGuard calls multiple functions to collect data from the victim, which is then stored in a file called “information.txt.” Targeted data includes the following:

- IP address

- Country/location

- Hardware identification (HWID)

- Operating system (OS)

- Log data (of infection)

The malware also has a separate function for taking a screenshot of the victim’s screen without their knowledge or consent. This only occurs once during the main info-stealing function of the malware. The screenshot is stored in the %AppData% directory alongside “information.txt” as “Screen.Png.”

Browsers

Like many other modern information stealers, BlackGuard has the functionality to obtain stored browser information to plunder a victim’s saved login credentials.

BlackGuard attempts to find the following information from the user’s browser:

- Logins

- Autofill information

- URL/History

- Download paths

As each browser stores its information in a different location, and uses its own method of storage, BlackGuard has specific functions to tackle info-stealing from the most popular browsers, including the following:

Message Applications

BlackGuard also targets popular instant messenger (IM) applications for pilfering sensitive information. It achieves this by reading information stored in the application’s relevant %AppData% directory.

As with browser data, each instant messaging application stores its data in different locations, so BlackGuard has individual built-in functions to search individual apps.

Let’s look at some examples:

- For Telegram’s collection function, it checks %AppData% before looking for the presence of Telegram.exe, plus a locally stored %tdata% folder that is generated by the messenger.

- For Pidgin, the collection function reads the "accounts.xml" file and copies the protocol, login, and password.

The method for stealing data from the other messaging applications is cruder; BlackGuard simply copies all files from each app’s respective application directory.

Application Name

|

Application Path

|

Telegram

|

%AppData%\Telegram Desktop\tdata

|

Pidgin

|

%AppData%\.purple\accounts.xml

|

Tox

|

%AppData%\Tox

|

Element

|

%AppData%\Element\Local Stroage\leveldb

|

Signal

|

%AppData%\Signal\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Proxifier

|

%AppData%\Proxifier4\Profiles

|

Discord Versions

Discord is a relatively new area of interest for malware authors, as it has become one of the most popular Voice-over-IP (VoIP) services globally, with over 150 million active monthly users.

BlackGuard will attempt to check for the existence of various versions of Discord on the victim’s machine before exfiltrating any user data stored locally, in hopes of finding passwords and accounts.

Name

|

Path

|

Discord

|

Discord\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Discord PTB (Public Test Build)

|

Discord PTB\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Discord Canary

|

Discord Canary\\leveldb

|

Cryptocurrency

A primary focus of BlackGuard is stealing cryptocurrency. Like Arkei infostealer, BlackGuard aims to cover all aspects of crypto applications, services and wallets, to ensure it is hitting all available crypto targets on the victim’s machine.

All the crypto resources targeted by BlackGuard are noted below:

Crypto Wallet Applications

Wallet name

|

Application Path

|

Zcash

|

\\Zcash

|

Armory

|

\\Armory

|

Jaxx

|

\\com.liberty.jaxx\\IndexedDB\\file__0.indexeddb.leveldb

|

Exodus

|

\\Exodus\\exodus.wallet

|

Ethereum

|

\\Ethereum\\keystore

|

Electrum

|

\\Electrum\\wallets

|

AtomicWallet

|

\\atomic\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Guarda

|

\\Guarda\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Zap

|

\\Zap\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Binance

|

\\Binance\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

atomic_qt

|

\\atomic_qt\\config

|

Frame

|

\\Frame\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Io.solarwallet.app

|

\\io.solarwallet.app\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

TokenPocket

|

\\TokenPocket\\Local Storage\\leveldb

|

Litecoin

|

\\Litecoin

|

Dash

|

\\DashCore

|

Chrome Wallets

Edge Wallets

Hardcoded Name

|

Hardcoded Path

|

Extension ID

|

Edge_Auvitas

|

\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\ klfhbdnlcfcaccoakhceodhldjojboga\

|

klfhbdnlcfcaccoakhceodhldjojboga

|

Edge_Math

|

\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\ dfeccadlilpndjjohbjdblepmjeahlmm\

|

dfeccadlilpndjjohbjdblepmjeahlmm

|

Edge_Metamask

|

\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\ ejbalbakoplchlghecdalmeeeajnimhm\

|

ejbalbakoplchlghecdalmeeeajnimhm

|

Edge_MTV

|

\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\ oooiblbdpdlecigodndinbpfopomaegl\

|

Oooiblbdpdlecigodndinbpfopomaegl (No longer present)

|

Edge_Rabet

|

\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\ aanjhgiamnacdfnlfnmgehjikagdbafd\

|

aanjhgiamnacdfnlfnmgehjikagdbafd

|

Edge_Ronin

|

\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\ bblmcdckkhkhfhhpfcchlpalebmonecp\

|

bblmcdckkhkhfhhpfcchlpalebmonecp (Relisted Link)

|

Edge_Yoroi

|

\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\ akoiaibnepcedcplijmiamnaigbepmcb\

|

akoiaibnepcedcplijmiamnaigbepmcb

|

FTP Clients

BlackGuard also attempts to search the victim’s device for two known File Transfer Protocol (FTP) services; FileZilla and WinSCP. These are both popular freeware applications with over a 100 million active downloads at the time of writing.

BlackGuard will attempt to obtain locally stored information pertaining to the victim’s recent and current FTP servers. It does this to gain access to potentially valuable data the victim has been transferring and interacting with.

High-Value Target Evaluation

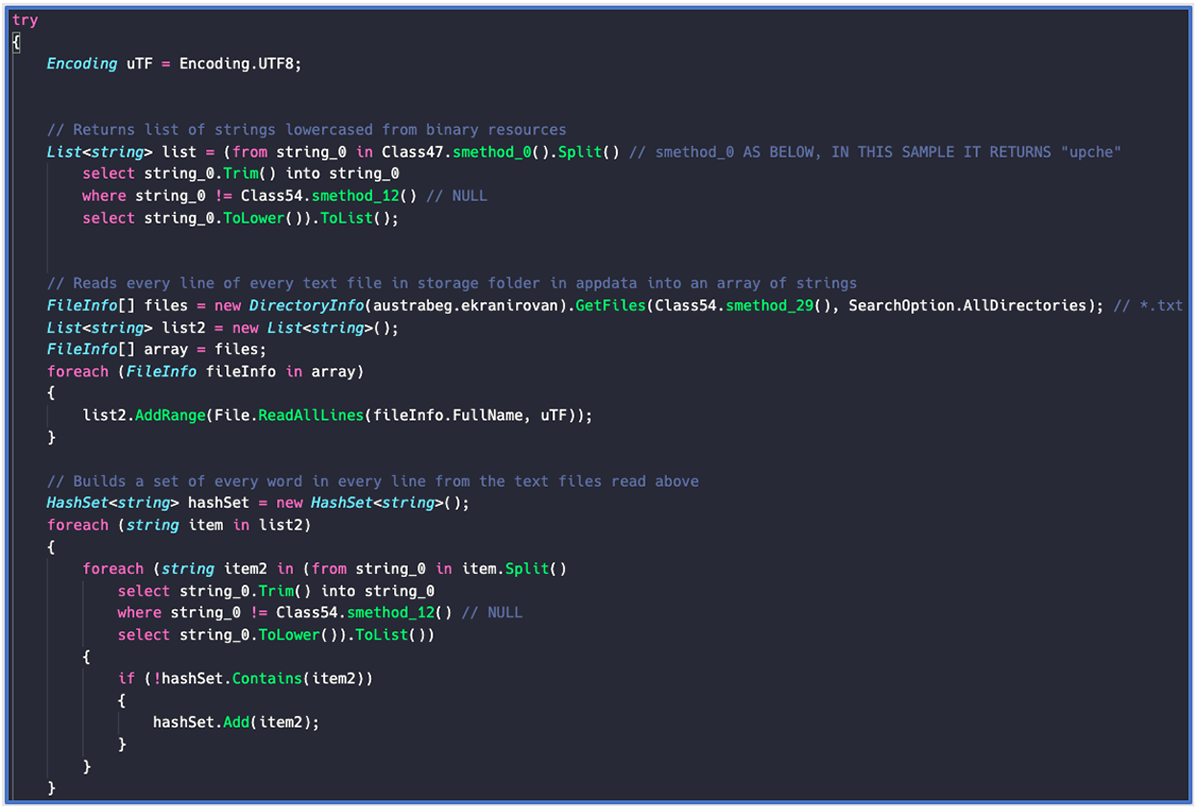

In the creation of a BlackGuard sample, a threat actor can provide a list of relevant strings for the malware to focus on. Located in the resource section of each sample’s binary, BlackGuard’s final information collection process involves the tokenization of these included strings.

The malware will seek out any references to these relevant strings, iterating through all the data it has gathered. If a string matches, it will be highlighted as a high-value target for the threat actor to note when reviewing successfully exfiltrated data.

The code for this activity can be seen in the following Figures 3 and 4:

Figure 3 – High-value target evaluation, part 1

Figure 4 – High-value target evaluation, part 2

As these string lists are defined on the creation of a new sample of BlackGuard, we’ve observed a degree of uniqueness in samples found in the wild. Many of the tokenized strings we’ve found are related to cryptocurrency, banking, and antivirus vendor websites.

By examining the resources of multiple BlackGuard samples, we have created a list of the most common strings targeted:

String

|

Category

|

admin

|

Administration

|

ads.google.com

|

Advertising

|

kaspersky.com

|

Antivirus

|

avast.ru

|

Antivirus

|

malwarebytes.com

|

Antivirus

|

chase.com

|

Banking

|

santander.com

|

Banking

|

www.hsbc.com

|

Banking

|

www.wellsfargo.com

|

Banking

|

www.jpmorgan.com

|

Banking

|

blockchain.com

|

Cryptocurrency

|

gate.io

|

Cryptocurrency

|

bitpapa.com

|

Cryptocurrency

|

coinpayments

|

Cryptocurrency

|

ton.org

|

Cryptocurrency

|

btc.com

|

Cryptocurrency

|

block.io

|

Cryptocurrency

|

coinbase.com

|

Cryptocurrency

|

payeer.com

|

Cryptocurrency

|

crypto.com

|

Cryptocurrency

|

paypal.com

|

Online Commerce

|

facebook.com

|

Social Media

|

$#!3301)&(*&$&*$#!234)&(*&$&*$#!234)&

|

Unknown

|

&(*&$&*$#!3301)&(*&$&*$#!234)&(*&$&*$#!234)&(*&$&*$#!234)

|

Unknown

|

Any matches are written to “search_link.txt” and saved to the temporary %AppData% directory along with all other stolen information.

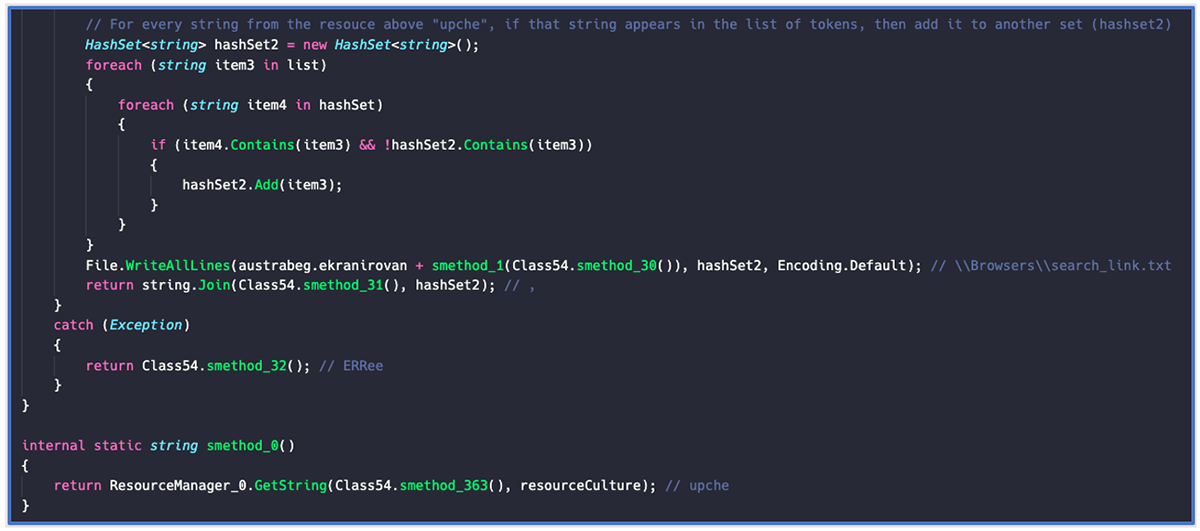

By viewing screenshots posted on the sales thread created by the malware author, we can identify where these matches are displayed in the command-and-control (C2) panel, as seen in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5 – Screenshot of BlackGuard C2 panel

Exfiltration to C2

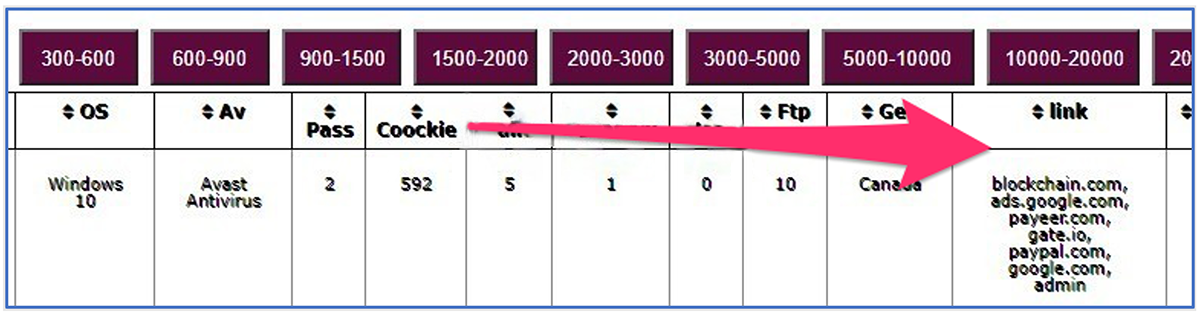

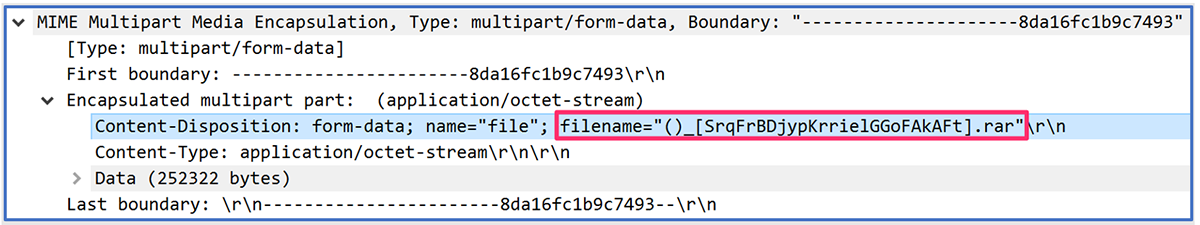

Once BlackGuard has copied all the information it has gathered into its temporary directory in %AppData%, it zips the information into a handy RAR archive with a randomly generated name.

The filename is generated using the country of the victim, as recorded from the IP information previously requested, and then concatenated with a pseudo-random string.

The string is generated from the following charset: “aytdgirlzxcvbnmasdfghjklqwertyuiopAABBFFGKKDS”

Example: (Ireland)_[SrqFrBDjypKrrielGGoFAkAFt].rar

Figure 6 – Generation of pseudo-random RAR filename

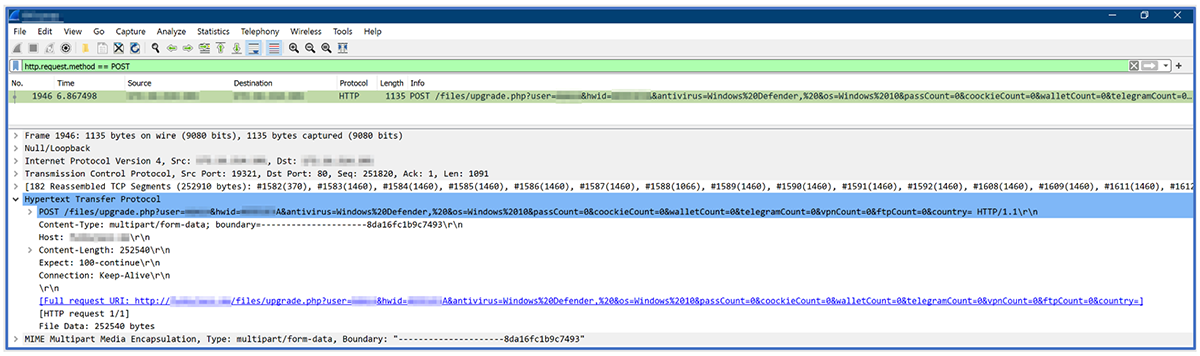

The newly created RAR file is then sent via a POST request to a hardcoded C2 server, as shown in Figure 7. The request includes some basic details to allow the attacker to quickly identify valuable targets, such as the following:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- High-value target evaluation result

|

Figure 7 – Interception of data via a POST Request

Figure 8 – POST request of data

In the examples shown above, the malware failed to generate the expected filename for the RAR archive, as our malware analysis took place in an offline and closed environment. Therefore, the IP address was not successfully gathered, and the geo-located country is missing from the filename (as seen in Figures 6 and 8).

Files Sent in POST Request

Item

|

Description

|

Browsers (Directory)

|

Data collected from Opera, Edge and Chrome. Contains cookies, downloads, history and results of high-value target search.

|

Chrome_wallet (Directory)

|

Data collected from Chrome Wallet extensions (from list above).

|

Edge_wallet (Directory)

|

Data collected from Edge Wallet extensions (from list above).

|

Files (Directory)

|

Files collected from the user’s profile (desktop, documents, etc.)

|

Telegram (Directory)

|

Telegram data stolen

|

Information.txt

|

Containing information regarding country, HWid, operating system and log date

|

Screen.png

|

Screenshot of user’s desktop

|

Conclusion

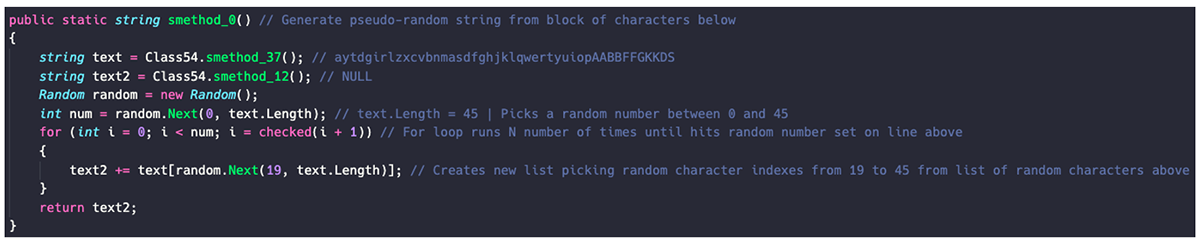

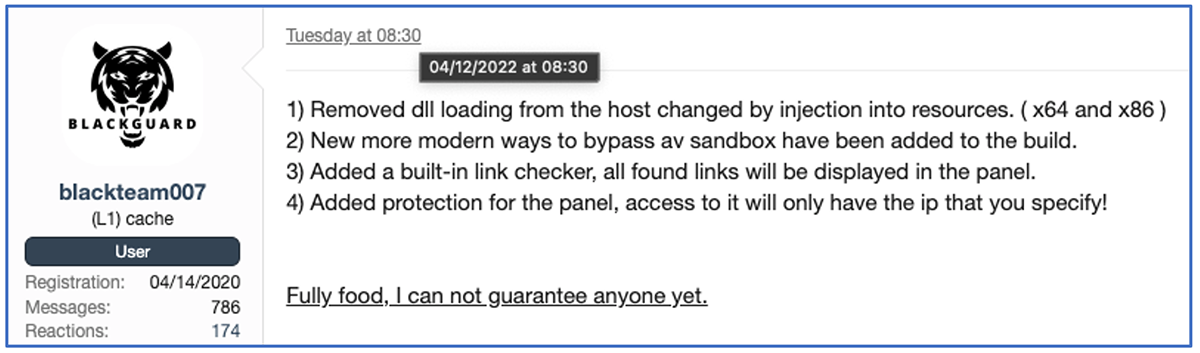

As malware infostealers evolve, so too does the market for them. BlackGuard is a complex threat that still seems to be in development, as seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9 – Malware author update log (translated from Russian to English)

As this threat becomes increasingly popular and widely distributed as a MaaS offering, and the malware’s attack vector varies, it’s difficult to map an exact diagram of a typical attack. Each attack is likely to be tailored to the requirements of the target, so it’s hard to know how this threat is likely to appear in a victim’s environment. Since this threat is priced reasonably inexpensively, it gives novice cyber-criminals access to advanced malware for a nominal fee.

It has become more common in recent years for people to store financial information and cryptocurrency data on their devices, for the sake of ease and convenience. This makes information-stealing from these devices an extremely rewarding pursuit for profit-driven threat actors. This is true whether the target is an individual or part of a larger enterprise.

With BlackGuard’s primary laser-focus on cryptocurrency data and wallet information, it is critical for crypto enthusiasts to add more effective security measures to their endpoints.

YARA Rule

The following YARA rule was authored by the BlackBerry Research & Intelligence Team to catch the threat described in this document:

import "pe"

rule Mal_Infostealer_Win32_BlackGuard

{

meta:

description = "Detects W32 BlackGuard Infostealer"

author = "BlackBerry Threat Research team "

date = "2022-14-04"

sha256 = "6AB3B21FA7CB638ED68509BE1ED6302284E8A9CD1A10F9B6837C057154AA6162"

license = "This Yara rule is provided under the Apache License 2.0 (https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0) and open to any user or organization, as long as you use it under this license and ensure originator credit in any derivative to The BlackBerry Research & Intelligence Team"

strings:

$a1 = { 06 91 06 61 20 AA 00 00 00 61 D2 9C 06 17 58 0A }

$a2 = "System.Data.SQLite"

$a3 = "FromBase64String"

$a4 = "BlockInput"

$a5 = "UploadFile"

$a6 = "Passwords"

$a7 = "Discord"

$a8 = "GetVolumeInformationA"

$a9 = "NordVPN"

$a10 = "OpenVPN"

$a11 = "ProtonVPN"

$a12 = "OperaCookies"

$a13 = "EdgeCookies"

$a14 = "ChromeCookies"

$b1 = "upche" wide

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x5a4d and

pe.imphash() == "f34d5f2d4577ed6d9ceec516c1f5a744" and

pe.number_of_sections == 3 and

pe.section_index(".text") == 0 and

pe.section_index(".rsrc") == 1 and

pe.section_index(".reloc") == 2 and

((all of ($a*)) or ((12 of ($a*) and all of ($b*))))

}

|

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

SHA256:

3df93a8c2843f1e91c7625685fbc4a7fc9438d8debf765d5a5bf9c62dbed6aef

6ab3b21fa7cb638ed68509be1ed6302284e8a9cd1a10f9b6837c057154aa6162

ac6fb63231a7cfc8380400721b6b2be8fd4c65f10947edb8b500f5779441338b

aadec91cc7481998ba59f2ad65005144417c7bde5e28114fc57cd04ee3551be8

8b6a82bd10fc3cab378e9c2023bee639ed81d1ee02fb882b8601f451466d76bf

C2 Domains:

hXXps://greenblguard[.]shop

hXXps://win[.]mirtonewbacker[.]com

hXXps://skazkahoho[.]space

hXXps://fuzzyjazz[.]me

|

BlackBerry Assistance

If you’re battling this malware or a similar threat, you’ve come to the right place, regardless of your existing BlackBerry relationship.

The BlackBerry Incident Response team is made up of world-class consultants dedicated to handling response and containment services for a wide range of incidents, including ransomware and Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) cases.

We have a global consulting team standing by to assist you, providing around-the-clock support where required, as well as local assistance. Please contact us here: https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/forms/cylance/handraiser/emergency-incident-response-containment

For similar blogs and news delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to the BlackBerry Blog.

About The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence Team

The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence team is a highly experienced threat research group specializing in a wide range of cybersecurity disciplines, conducting continuous threat hunting to provide comprehensive insights into emerging threats. We analyze and address various attack vectors, leveraging our deep expertise in the cyberthreat landscape to develop proactive strategies that safeguard against adversaries.

Whether it's identifying new vulnerabilities or staying ahead of sophisticated attack tactics, we are dedicated to securing your digital assets with cutting-edge research and innovative solutions.