13 Deadly Sins When Dealing With APT Incidents — Part 2

Someone has breached your organization. Now you and your team are in the pressure cooker: sleeping in shifts, juggling technical issues with analysis and decisions, and preparing executive briefings on your incident response progress.

This is the point where incident responders are more likely to commit some of the “13 deadly sins of incident response,” as we call them, potentially grave mistakes often made in the heat of battle — mistakes that can needlessly sabotage your response efforts and give attackers the advantage.

In Part 1 of our series, we focused on the first four “deadly sins,” most commonly committed while preparing for a data breach. Here in Part 2, we are past the preparation stage: An active breach is now underway, and additional mistakes are likely. We know this because we are drawing from the 100-plus years of collective incident response (IR) experience of the BlackBerry® Cybersecurity Services Incident Response Team.

The Fifth Deadly Sin of Incident Response: Panicking, Cutting External Connectivity, or Wiping Systems Too Soon

Although this is No. 5 on our list of IR “sins,” the top rule in incident response should always be “DO NOT PANIC.” However, this is often easier said than done.

Hearing the words, “You’ve been hacked,” often creates a sense of fear. This can trigger knee-jerk reactions and a desire to fix the situation ASAP. Resist that impulse: You need to consider your next actions carefully.

One of the big decisions incident response teams and CISOs may have to make is around connectivity: During an active data breach, should you disconnect the entire organization? Sometimes it is a necessary course of action — but it can also be a big mistake. In all cases, it is a decision you should make with great care.

Important points to consider:

- If you disconnect the organization, you immediately place a huge amount of pressure on your incident responders. Before safely reconnecting to the internet, there is an expectation they will a) find every impacted system in the environment; b) analyze the activity; c) understand the malware’s behavior (and block it); and d) identify the initial intrusion vector — all while taking the necessary remediation steps to remove the attacker.

You will also need to take steps to prevent the threat actor from easily re-compromising your environment — with all the inside information they managed to gather during their time inside your environment. That’s a very tall order.

- Depending on the size of the incident, your environment, and the resources you can bring to bear, this can represent several weeks of 24x7 work to accomplish. If the initial intrusion vector is an external-facing application, this can involve development of changes to fix a vulnerability, as well as testing, to ensure the attacker does not immediately return.

- Will the organization tolerate — and can your company afford — this potential downtime? It may have a significant impact on sales, clients, employees, and profit. Organizations will also need to consider the reputational risk, and carefully manage internal and external communication.

If the consequences of killing connectivity are so significant, why do we sometimes see organizations choose this path? The key advantage of a complete shutdown is the effective removal of access for the external threat actor, preventing them from stealing additional data or taking destructive measures.

- Good visibility of what the attacker is doing, as well as intelligence on their likely end goal, helps you make informed decisions. Surgically containing the incident at “patient zero,” before lateral movement has taken place, is the ideal response when prevention has failed. As soon as the actor moves laterally and drops additional backdoors, the task becomes much harder. Multiple back doors can be a sign of an advanced persistent threat (APT) or nation-state attack. At this time, an investigator who is experienced with nation-state attacks should methodically and fully scope the incident before doing anything that alerts the threat actor that they have been discovered.

If the in-house team lacks the capability or experience to weigh the factors swiftly and make these tough decisions, sign an incident response retainer as soon as possible — preferably before a breach occurs, or at least when it is discovered. This ensures a service provider will assist within the contracted service-level agreements (SLAs) and help guide your initial response.

Wiping Systems During Incident Response

Another common panic reaction is to immediately reimage or wipe the affected system. This is often a default policy for any kind of commodity malware that is detected on a “system of interest.” Again, it can also be a big mistake, depending on the circumstances. In the case of a serious incident involving an APT attack, for example, valuable evidence will be destroyed by reinstalling or reimaging the infected host.

Our BlackBerry IR team has observed multiple cases where an IT team thought they took the right steps by reinstalling prior to taking forensic evidence, but that decision eventually led us to an investigative dead end.

In situations where a breach has just been discovered, an incident responder is typically unable to determine whether a particular host was the initial entry point, how the attackers got in, or if they used it as a pivot point to another system.

If you make this error of prematurely reinstalling what you assume to be “patient zero,” hopefully you are lucky enough to have NetFlow logs, which will still help you make a “best guess” about other systems that might also have been affected.

Standardized Approach to Incident Response

A security team needs to have a standardized approach for the IT team to act upon and often this means going off of specific keywords. “Mimikatz,” “Cobalt Strike,” and “Trojan” are examples and can help you determine the gravity of a detection.

Another best practice is using a combination of things: the type of server that is compromised along with keywords. Was “Trojan” detected on both a domain controller and a workstation? One of these combinations is a higher priority.

There must be a clear understanding of when to take preliminary forensic evidence and when to continue with operations. If in doubt, always take forensic evidence BEFORE reimaging a system.

A very good example of fitting antivirus detections into a method of relevance is Nextron's Antivirus Event Analysis Cheat Sheet.

Eventually, the internal work method will depend on the security software that is in place.

The document gives a particularly good overview of how a security team can determine if an event is significant, and so requires incident response activities, or whether the antivirus quarantine performed by the default endpoint protection platform (EPP) installed on the machine would be enough to mitigate the issue.

As one example, finding a Mimikatz detection on your domain controller — or on any server within your environment — should trigger immediate incident response activities. It is not something an organization would typically expect to find “laying around.” However, getting a potentially unwanted program detection on a client system where the user has admin privileges might require other means to resolve the issue.

The Sixth Deadly Sin of Incident Response: Trusting Your Comms Channels

Communications about security incidents are often highly confidential and sensitive. The last thing you can afford to do is accidentally share your response plans with the attackers themselves. (Sounds crazy, but it happens.) Sometimes an incident might be linked to an insider threat, or the attacker has access to internal email or online collaboration tools such as Slack. Avoid committing deadly sin No. 6, where you assume normal comms channels are secure.

Instead, consider the need to use out-of-band, encrypted, and trusted means of communicating between the teams handling the case.

Also, on multiple occasions, our incident response team witnessed administrators using cleartext email to send credentials and other sensitive information during an incident. APT actors often have full control over email servers and have performed network surveillance to extract credentials from cleartext traffic. In one case we saw the threat actor reuse credentials created for the incident response teams’ recovery actions.

It is important to realize how vulnerable unencrypted traffic can be, even internally. Based on our experience, some advanced threat actors will monitor emails from critical staff, such as administrators and C-level executives, or monitor firewall logons over unsecured protocols such as telnet.

When dealing with an incident it is important to keep details on a need-to-know basis. Think about maintaining a calling tree and primarily sharing information with security staff, key administrators, and legal representatives. Even though the natural response during an incident is to quickly call for as much help as one can, we recommend you continue with daily operations to avoid alerting threat actors. Allow the incident to be handled by the dedicated team because you never know when you might be dealing with an insider threat.

The Seventh Deadly Sin of Incident Response: Uploading Samples to Online Services

It can be risky to upload unknown malware samples to public analysis platforms such as any.run, VirusTotal during your response, especially when dealing with an APT. This is a key point, because you may not know you are dealing with an APT at the time you upload the malware sample.

Be careful what you upload, for the following reasons:

APTs will monitor hashes of uploaded files on analysis sites because they often create a unique hash for every campaign or even each victim. Leaked emails from these groups reveal they actively monitored VirusTotal to know when any of their implants were uploaded — by simply querying if the file exists on the website.

Malware often contains victim details, such as hardcoded proxy credentials or machine hostnames in the configuration; or when the command-and-control (C2) server that the malware is configured to use is linked to the victim itself. For example, the domain used by the attackers might be the victim’s domain name with a minor typo.

The fact that an executable hash is not on a site like VirusTotal should be an indicator that it is not common, and so may warrant some additional focus. APT’s often create hashes for their tools that are unique for each campaign or client, as part of good operational security.

A clear example of a threat group tracking their own hashes on VirusTotal comes from the leaked Hacking Team emails on Wikileaks. The site publishes news leaks and classified media provided by anonymous sources. According to news reports, the Hacking Team was an Italian information security company that sold offensive intrusion and surveillance capabilities.

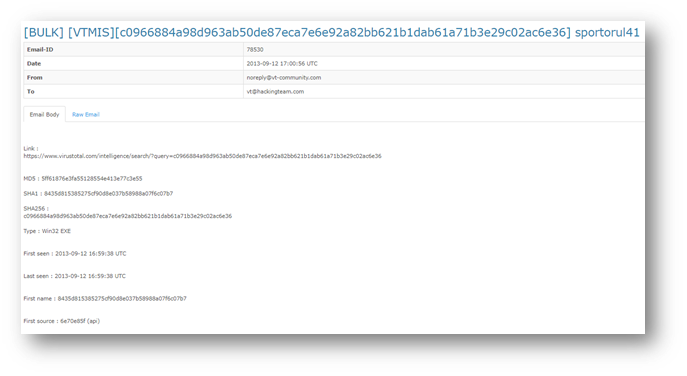

As a reference, in the Wikileaks page below see (Figure 1), you can see the user “vt@hackingteam.com” receiving a notification from VirusTotal that the hash they monitor was submitted:

Figure 1 – Extract from Wikileaks – VirusTotal alert for c0966884a98d963ab50de87eca7e6e92a82bb621b1dab61a71b3e29c02ac6e36

Following that, we find a forward to the rest of the concerned Hacking Team members asking whether it is the latest version of their implant:

“Questo e' roba nostra, fortunatamente solo Eset lo rileva come spyware generico (non come Davinci) e, se non vado errato, il submit viene proprio da loro. Guido puoi verificare da che cliente arriva? Domani comincia a lavorare sulla firma di eset e vediamo come si evolve la situazione: se rimane una signature isolata rilasciamo un minor upgrade, se la firma si propaga seguiamo il caso di "leak scout" gia' ben documentato sul documento ‘crisis procedure.’”

The above translates to:

“This is our stuff, fortunately only Eset detects it as spyware generic (not like Davinci) and, if I'm not mistaken, the submit comes right from them.

Guido, can you check which customer it comes from?

Tomorrow start working on Eset's signature and let's see how the situation: if an isolated signature remains we issue a minor upgrade, if the signature spreads let's follow the case of ‘leak scout’ already well documented on the ‘crisis procedure’ document.”

This does sound like the team had a proper crisis procedure when one of their “scouts” got identified, and they are asking which “customer” (aka, a client using their proprietary intrusion tools) submitted this sample to VirusTotal. This is proof that advanced threat groups actively track online submission sites for their own implants. Once threat actors know someone detected their implant, they can either deactivate it and stop the campaign, or push out an update and attempt to keep the implant “under the radar” for as long as possible.

Another interesting entry in the WikiLeaks dump is the email that was sent to an external “client” in response to a support ticket. Someone named Marco Valleri explains how a particular implant was uploaded to VirusTotal, and even provides a recommendation to stop attacking the “target” for the time being:

“Vi preghiamo pertanto di non effettuare piu' alcun tentativo di infezione su questo target, di non utilizzare piu' il server FTP in questione e di dismettere l'anonymizer non appena tutti gli agenti ‘legittimi’ abbiano scaricato la nuova configurazione.”

Which translates to:

“We, therefore, ask you not to make any attempt to infect this target anymore, to stop using the FTP server in question, and to discard the anonymizer as soon as all the ‘legitimate’ agents have downloaded the new configuration.”

This is another example that reveals something crucial: Both network defenders and threat actors look at online malware databases.

It is good practice, however, to check file hashes against trusted public services to see if they are already there, and we commonly check hashes against VirusTotal when starting a new engagement. When we do this, we often see that it was uploaded for the first time only a few days earlier. On many occasions, we have discovered it was a member of the customer security team who uploaded the files while trying to research the incident.

To conclude, uploading files to VirusTotal, or any other service, might have a number of undesired consequences, especially during an incident:

- During an APT case, the threat actor can take active measures to hide itself, or worse, become destructive, escalate exfiltration, or attempt to keep the unknown backdoors hidden for some amount of time.

- We have seen actors change out their backdoors to a completely different family within a short time after their malware samples were posted to public repositories, changing their TTPs in order to remain hidden. It is also common for advanced persistent threats to go dormant if they think they have been detected, in hopes of staying hidden, only to restart their activities later.

- If a researcher stumbles on your uploaded hash, which is likely (vendors and researchers frequently probe VirusTotal, looking for new and interesting samples), your incident might end up the subject of a public blog or news report. If a publication appears without your prior knowledge of a compromise, it may force your organization to make a public statement before you are ready.

- Malware you upload also might contain “personalized” configurations you should not divulge. In one example, we saw a backdoor which had a hardcoded user account configured for the company proxy. In another example, we identified polymorphic malware that added the victim’s hostname string as a sort of infection chain.

So exercise caution and good judgment before you upload malware to an online portal. However, please take note: Once you confirm that there is no specific detailed information in the sample, and you are sure that the attack was fully mitigated, uploading to an online portal and providing the malware is highly encouraged. It adds to our collective threat knowledge and helps protect the rest of the community.

The Eighth Deadly Sin of Incident Response: Actively Probing Command-and-Control Systems

Depending on the type of attack you are experiencing, it is often risky to actively interact with command-and-control servers, such as by pinging the server in question or resolving malicious domain names. Running offensive tools against the server — even after the incident — may violate regulations in your region or the region where servers are located. Also, threat actors often abuse compromised servers belonging to innocent third parties, so any offensive action against a C2 server may technically be punishing another victim, not the perpetrator.

When tools such as “nslookup” or “dig” are used to query “evilsubdomain[.]evil[.]domain,” these queries will be redirected to the DNS server that is controlling the evil[.]domain nameservers to provide the appropriate response. Some groups may be monitoring for such queries. So taking the resolving IP from any available DNS logs would be recommended instead of actively contacting DNS servers possibly controlled by the threat actors. Alternatively, use passive DNS services if logging was not in place at the time of the activity.

Advanced persistent threats are known for purposefully leaving hints for reverse engineers or security analysts that tip off the threat group. A DNS canary is a fake domain left in the strings of a binary sample, purposefully inserted into malware so an unwary analyst would try to resolve the domain and see which IP it resolves to. This example is another reason why you should always research C2 server information from passive sources where possible, especially when handling an incident involving advanced attackers.

The Ninth Deadly Sin of Incident Response: Failing to Understand Response Timelines

Timing is critical in advanced attacks. Either the team may need to take their time — in the case of a nation-state attack that has moved laterally — or you need to act quickly, such as in the case of a ransomware attack. The speed of your response depends on the situation you are dealing with, and the team’s experience and expertise.

The image below of the cybersecurity “kill chain” is an illustration of key milestones in a typical attack timeline, and understanding this sequence of events may help provide real-time visibility into your adversary’s activities — and their likely next steps. Knowing what stage of an attack an actor is engaged in, and intelligence of what their final objective may be, enables you to make good risk-based business decisions.

Figure 2 — Cybersecurity “kill chain”

In addition to representing the steps attackers typically take to accomplish their goals, the model provides insights the incident responder can use to determine the best course of action at a given time. When the actor is in the initial phase of the attack lifecycle (kill chain stages 1 to 4), it’s best to try to intervene as quickly as possible.

If the detection is happening when the attacker is already in a later stage of the kill chain (after the lateral movement), the incident needs to be fully scoped in order to create and execute an effective remediation plan — and all interventions need to be carefully considered in advance when dealing with APTs.

In our experience, APT actors do not rely on a single means of access and will always have multiple backdoors. That is why incident responders must attempt to identify all points of access during the identification or scoping phase, before taking any containment actions.

This is the point where experience comes into play; having highly experienced and trusted senior incident responders to help advise you, based on their previous encounters with the same or similar groups, provides a significant advantage. They can recognize where the attackers are in their attack lifecycle, and devise the best course of action for that stage of the kill chain.

Failing to identify an attacker’s full scope of access before remediating can result in a failed incident response, with advanced threat actors often laying low for a period of time after they become aware they were detected. This period of inactivity — or increased stealth — can last from a few days to several months. Then they often attempt to use secondary or tertiary backdoors to regain access and resume activities. As a first action, consider improving visibility. This preferably occurs as part of proactive preparation, before an incident is discovered, but it can be accomplished during an active incident to enable you to detect and track advanced actor activities in near real-time. Some common actions that will raise visibility are:

Conclusion

The initial phase of incident response is a high-risk time for your organization. It’s also a crucial period to avoid any "deadly sins” that can worsen the situation, and in some cases, increase the damage from an incident. In Part 3 of our series, we’ll discuss the four final deadly sins of incident response — focusing on things that could go wrong during the recovery phase after an incident. It might surprise you to learn what tends to be forgotten during recovery, and how these “sinful” omissions can sometimes lead to a harrowing game of cat-and-mouse between attackers and defenders.

Stay tuned for our next installment!

About BlackBerry Incident Response Services

BlackBerry provides incident response that can help you mitigate the impact of any breach, ensure your recovery follows best practices, and secure your IT environment for the future. Our cybersecurity experts provide answers to your questions so you can protect your IT environment during the current attack and defend against future cyberattacks.

About Rocky De Wiest

Rocky De Wiest is a Principal Incident Response Consultant.

About The BlackBerry Incident Response Team

The BlackBerry Incident Response team is made up of world-class consultants dedicated to handling response and containment services for a wide range of incidents, including ransomware and Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) cases. If you’re battling malware or a related threat, you’ve come to the right place, regardless of your existing BlackBerry relationship. We have a global consulting team standing by to assist you, providing around-the-clock support where required, as well as local assistance. Please contact us here.