Lynx on the Prowl: Targeting SMBs with Double-Extortion Tactics

Summary

Ransomware gangs have played a substantial role in shaping the cyber threat landscape over the last decade, operating with impunity with ever-more aggressive tactics. Despite increased focus from law enforcement, 2023 saw a record $1 billion+ in ransoms paid out by victims. 2024 has brought with it a flood of old and new cybercriminal gangs, all trying to grab a piece of this lucrative pie.

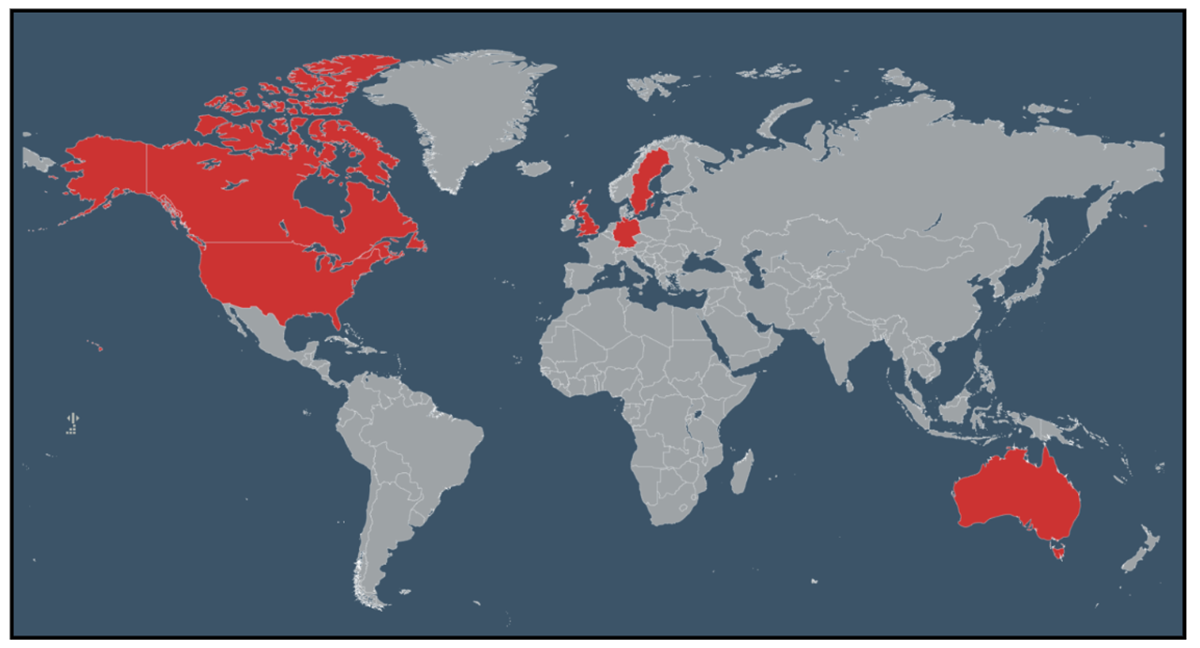

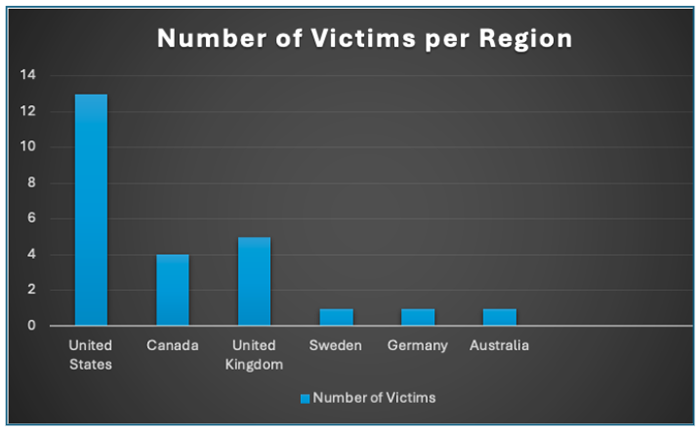

During our routine monitoring, the BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence Team noticed an uptick in activity by one of the newer groups dubbed “Lynx.” The threat group first appeared in mid-July and quickly racked up over 25 victims primarily across North America and Europe over the following weeks. Claiming to operate “ethically” by not targeting hospitals, governmental organizations, or nonprofits, the group instead preys on small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) across a wide variety of industries.

Our interest in the group was further piqued when, upon delving deeper into the ransomware, we noted that it appeared to have strong correlations with the file-encryptor utilized by another ransomware extortion operation called “INC Ransom” (aka INCRansom or INC Ransomware), which led us to dig deeper.

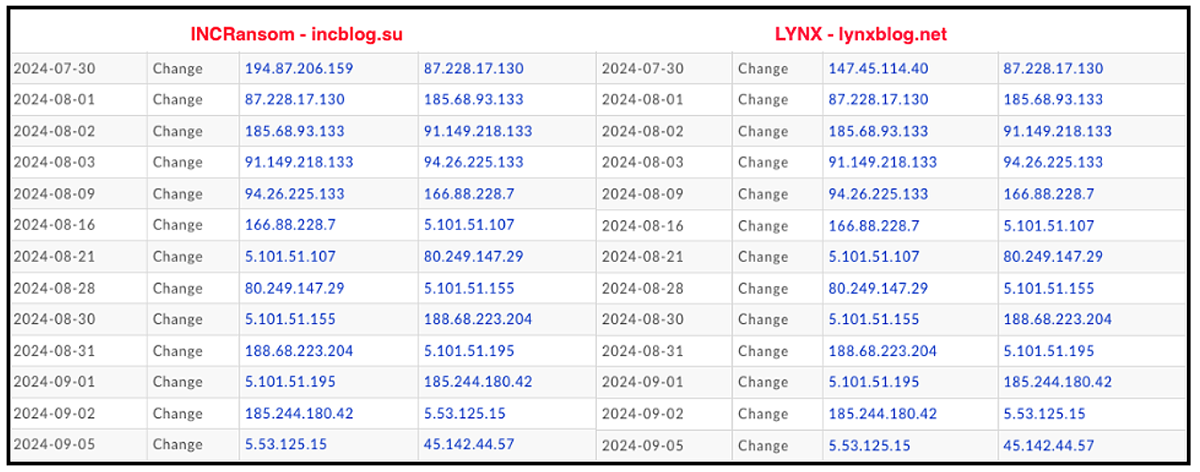

As a result of our investigations, we can state with a high degree of confidence that Lynx and INC Ransom share near-identical static code structure and operate almost identically when dynamically running. Additional correlations include the use of the same email address – gansbronz[at]gmail[.]com – in the registry information of the public leak sites of both groups, the same method of storing their ransom notes within their file-encryptors, and the fact that both groups appear to be sharing the same pool of IPs.

In this blog, we’ll examine this relationship between the two threat groups further.

Who are the LYNX Ransomware Group?

Like many ransomware operators, the Lynx group employs a double extortion strategy when targeting their victims. Once they gain unlawful access to a system, they exfiltrate sensitive data prior to encrypting it on the host device or network. The stolen data is then published on their leak sites along with a blog entry naming and shaming the victim.

The stolen data may then be further leveraged by the group in ransom negotiations, with the threat that additional information may be published if the victim organization does not comply with their ransom demands.

In the limited time the group has been active, Lynx has targeted a variety of industries namely within but not limited to North America and Europe.

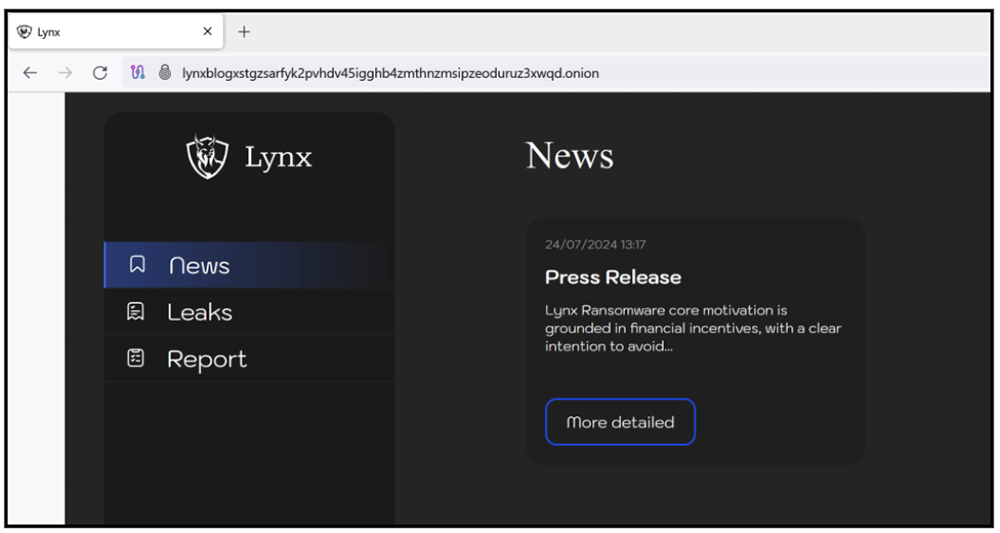

Figure 1: LYNX blog page.

Lynx maintains both a surface web and dark web leak site along with a series of mirrored sites located at “.onion” addresses. This is presumably to ensure uptime, should one or more sites be taken offline by law enforcement.

They also employ their own encryptor which, as mentioned above, appears to have been developed using the same codebase as the one previously utilized by the INC Ransom group. Researchers digging into this similarity have previously noted that running samples from both ransom groups through BinDiff, an open-source comparison tool for binary files, revealed a 70.8 percent match in shared functions.

Code reuse is common among cybercriminal groups. Doing so achieves multiple goals. By building on foundations already laid by other groups, threat actors can cut costs, conserve time, and put all their resources into developing their own attacks, leading to more campaigns with more successful outcomes.

Technical Analysis

To date, a handful of samples related to the encryptor utilized by the Lynx group have been identified in the wild. All samples appear to be written in C++, and lack any form of packing or obfuscation to impede analysis.

Once pre-encryption objectives such as gaining initial access and data exfiltration have been conducted, the ransomware may then be deployed and detonated on the compromised victim's environment. The ransomware itself is designed to be executed via the command-line console, supporting several optional arguments. This enables an attacker to customize their approach for file-encryption to coincide with their goals.

SHA-256

md5

|

ecbfea3e7869166dd418f15387bc33ce46f2c72168f571071916b5054d7f6e49

74ae58a716aa834949388ee1574788e0

|

ITW File Name

|

win.bin

|

Compilation Stamp

|

2024-08-04 06:49:12 UTC

|

File Type/Signature

|

X86 PE

|

File Size

|

164.00 KB (167936 bytes)

|

Compiler Name/Version

|

MS Visual Studio 8.0

|

PDB path

|

E:\Lynx\Release\Lynx.pdb

|

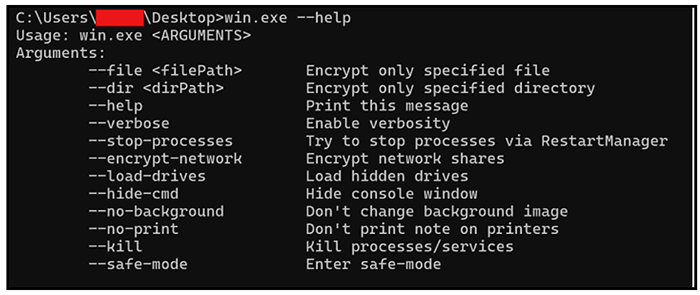

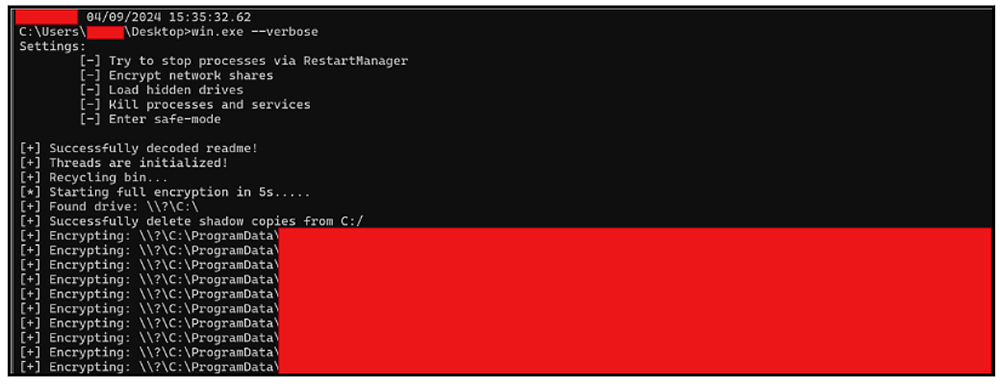

Figure 2 below shows the options that the ransomware supports, with an explanation of each displayable by invoking it with “--help.”

Figure 2: Lynx encryptor's help menu.

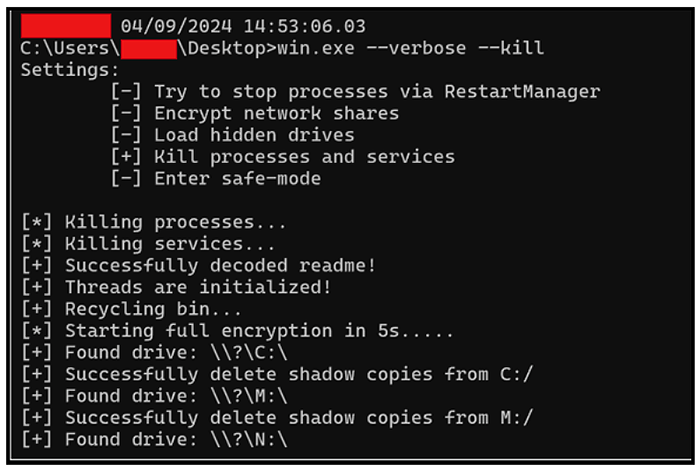

Upon execution, the malware further supports a “--verbose” mode that will print a list of operations the ransomware is conducting as it is dynamically running, as you can see in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Lynx encryptor running verbose mode.

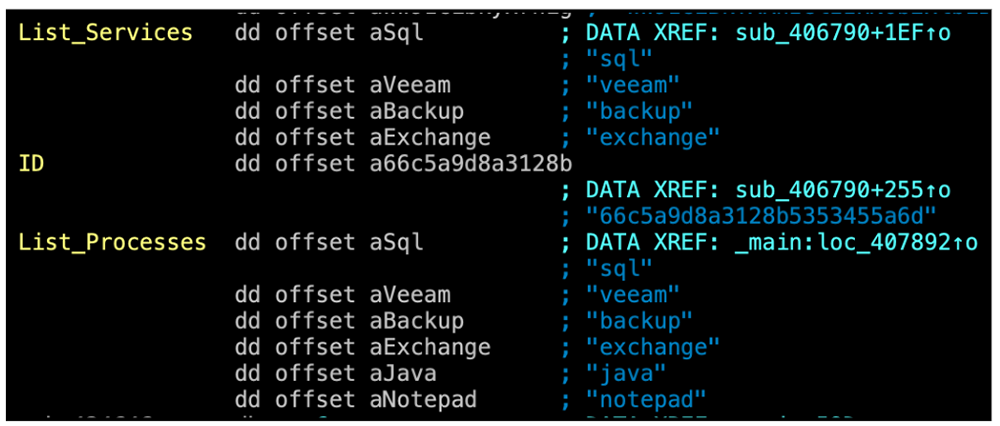

Each optional argument works as described, and should the “--kill” switch be selected, a specific list of processes and services will be targeted for termination, should they be present on the machine:

- SQL

- Veeam

- Backup

- Exchange

- Java

- Notepad

Figure 4: Process and services termination list.

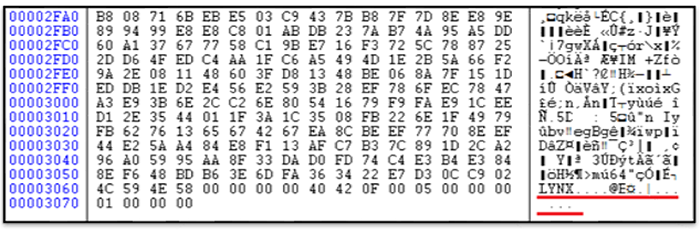

When encrypting files, the ransomware will append a new file-extension “.LYNX” to all applicable files and also appends an additional few bytes of code to each. This activity is performed by numerous ransomware encryptors to signify successful encryption and to help prevent double-encryption of already-ransomed files, if the malware happens to re-execute.

Figure 5: The file extension “LYNX” is appended to each encrypted file.

In order to prevent a victim’s device becoming inoperable, the malware omits certain file-types and Windows folders from encryption. This serves a dual-use purpose by speeding up encryption and preventing critical Windows programs becoming inaccessible, which would “brick” the device and ruin the group’s chance at holding it to ransom.

These directories are omitted by Lynx:

- \Windows\

- \ProgramFiles\

- \ProgramFiles x86\

- \Users\*\AppData

These file-extensions are omitted by Lynx:

Encryption

The Lynx file-encryptor utilizes AES-128 in CTR (Counter) mode when encrypting files. Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is commonly weaponized by ransomware groups for their file-encryptors. Additionally, the encryptor’s code includes an implementation of the Curve25519-donna algorithm to generate a shared “secret,” whilst the attacker’s public key is embedded into the code of the malware. Curve25519 is one of the fastest curves in elliptic-curve cryptography, offering 128 bits of security (256-bit key size). It is not covered by any known patents, making it a valuable addition to a cyber-gang's toolbelt.

The encryptor then computes the SHA-512 hash of the shared secret, and the first initial 16-byte (128 bits) of this hash is utilized as the key to encrypt the victims' files using AES-128.

To increase the encryption speed, the encryptor encrypts 1000000 (1 MB) in increments of every 6000000 (6 MB). Without gaining access to the private key generated by the threat actor, the victim’s files cannot be decrypted.

Figure 6: Encryption in progress (verbose mode).

Who is INC Ransom?

Appearing in the wild in July 2023, INC Ransom is another extortion-based ransomware group that has grown in notoriety over the past 12 months to become one of the most active ransomware groups of 2024. The group was extremely active in the later stages of 2023, before taking a brief hiatus heading into the current year. Upon its return, it was noted that the ransomware utilized by the group had seen minor iterative changes and new leak-site infrastructure stood up.

The group operates as a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS), often employing double-extortion ploys that involve stealing critical data before deploying their ransomware to encrypt compromised devices. This is leveraged to threaten the victim, pressuring them into paying the group’s ransom demands or risk their data being published via its public leak-site.

Unlike Lynx, INC Ransom makes no empty promises of acting ethically and has been known to aggressively target all sectors in the past, including healthcare, education, technology, and government entities.

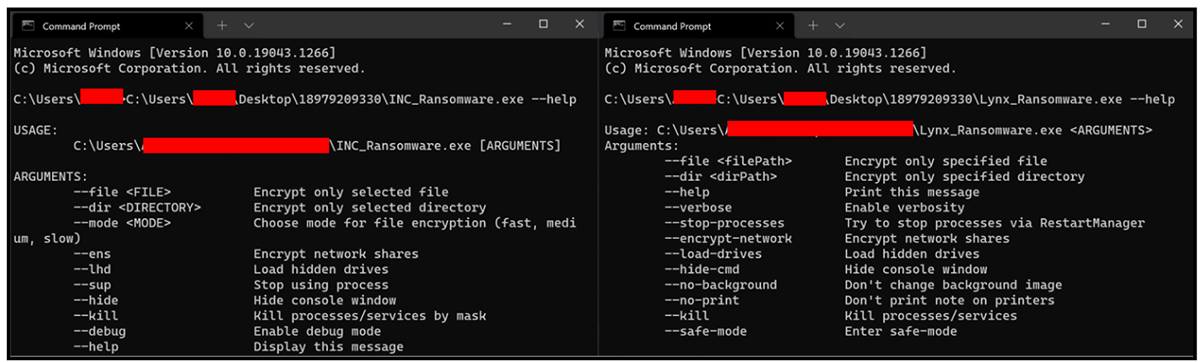

Upon closer inspection, BlackBerry threat researchers noted that code and modes of operation carried out by Lynx directly correlated with recent samples of the file-encryptor used by INC Ransom.

Figure 7: Comparison of INC Ransom (left) and Lynx (right) file encryptors.

According to third-party reporting site Ransomware.live, INC Ransom was one of the top 10 most active ransomware groups of 2024 at the time of publication.

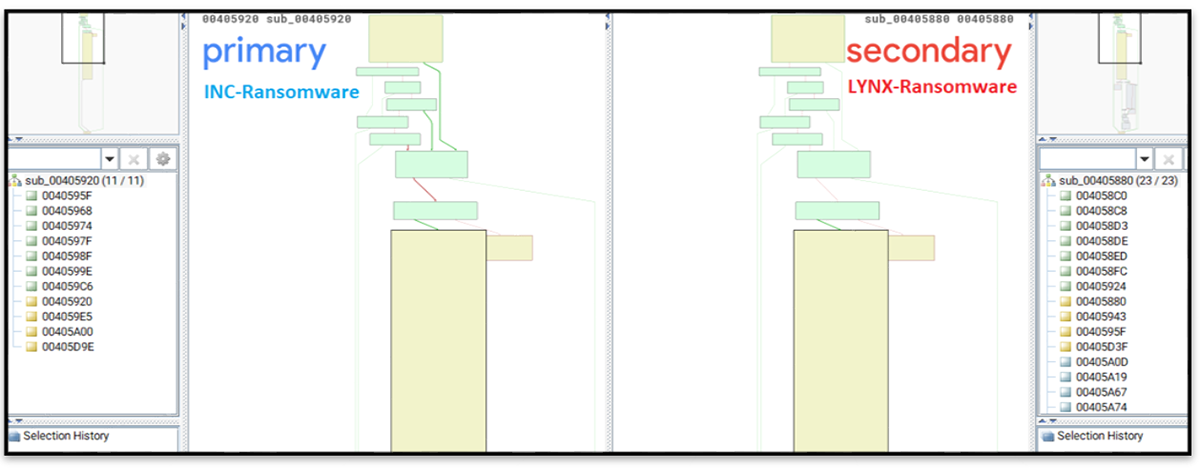

Lynx additionally appears to share a lot of its code-base with INC Ransom:

Figure 8: BinDiff diagram comparing INC Ransom and Lynx.

So what could explain this apparent similarity between the two groups? The most striking piece of information reported so far is that the INC Ransom source code may have been sold via a cybercriminal underground forum back in May. Cyber threat intelligence group KELA discovered that a user calling themselves "salfetka" had announced the sale of both the Windows and Linux/ESXi versions of INC Ransom on the Exploit and XSS hacking forums, to the tune of a cool $300,000.

KELA security researchers have since attempted to verify the authenticity of the sale, noting that technical details provided by “salfetka” align with public analysis of INC Ransom samples. Industry analysists additionally noted that around the time of the alleged sale, the INC Ransom operation was going through some changes that might suggest a rift between its core team members or even a split within the group. However, there are no official announcements on INC's websites about the source code sale, fueling speculation that the code may have been stolen by a disgruntled former member of the group.

At this stage of our investigation, BlackBerry cannot confirm nor deny any information about the potential sale of INC Ransom’s source code. However, we can state with a high degree of confidence that Lynx and INC Ransom share near-identical static code structure and operate almost identically when dynamically running. Additionally, at the time of writing, both threat groups appear to be operating independently of one another, and both are currently active across the threat landscape.

An additional correlation can be found in the registry information for the leak sites of both groups. The same email address – gansbronz[at]gmail[.]com – was used in the registry information of the publicly accessible Internet (aka the clearnet, or surface net) leak sites of both groups, and they have also both been sharing the same pool of IPs, which are rotated regularly and typically host both sites (clearnet and dark net) in tandem.

Figure 9: Domain hosting history results from DomainTools.

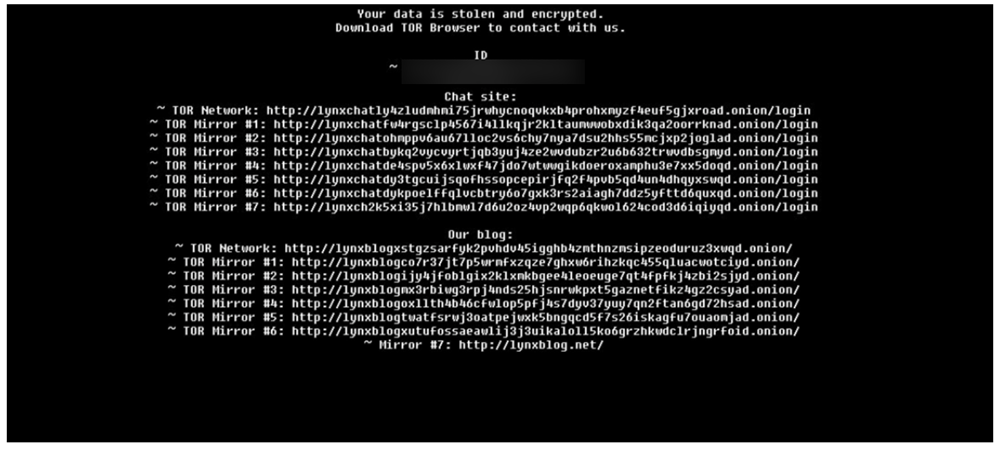

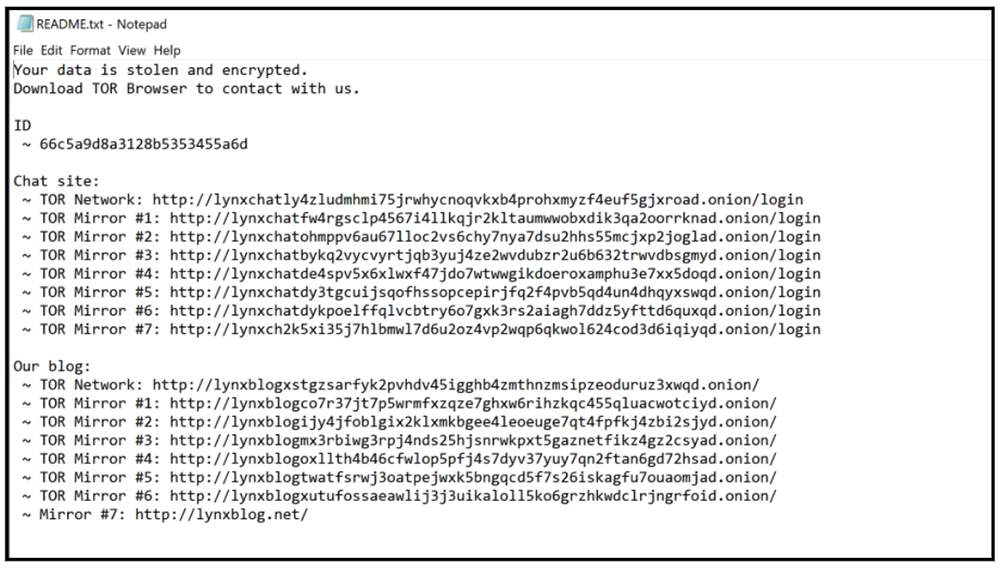

Ransom Note

Both INC Ransom and Lynx additionally share the same method of storing their ransom notes within their file-encryptors. Both contain a Base-64 encode blob that is decoded to produce both the background change to the desktop, signify to the user their device has been affected by ransomware, and generates the “README.txt” file that is also dropped by the ransomware.

Figure 10: Desktop background change.

It has been noted that some minor deviations were identified between observable Lynx samples and their ransomware notes. However, references to its clearnet web site and leak site remain consistent within all Lynx samples.

Figure 11: Lynx ransom note.

Network

As noted, Lynx has both a surface website based on the publicly accessible Internet, and numerous “.onion”-based sites on the dark web. This tactic is most likely used by the group to achieve some redundancy if ever some part of their operations were taken down.

Figure 12: Lynx’s dark web leak site - main page.

The Lynx group has a press release pinned to the front page of both their clearnet and dark net sites, explaining that they are financially motivated and committed to avoid targeting emergency services and non-profit organizations, a pledge they’ve thus far maintained — unlike INC Ransom, who target indiscriminately, including healthcare, education, and even charities in some cases. Recent INC Ransom victims include a U.S. subsidiary of tech giant Xerox, and NHS Scotland, the Scottish branch of the UK’s National Health Service.

INC Ransom even went so far as to publish a snippet of the alleged 3TB of data it stole from Scotland's NHS healthcare group, which included patients' medical test results (both adults and young children), medication information, and the patients' full names and home addresses. The contact details and full names of the medical professionals treating them were also visible. The ramifications of this type of data being publicly available on the Internet can only be imagined.

Figure 13: Lynx leak site – pinned press release.

As with most RaaS groups, Lynx employs a double extortion strategy when targeting a victim. This process typically kicks off with the group first gaining illicit access to the victim’s device or network, then exfiltrating critical or sensitive data prior to engaging their ransomware. This practice is calculated to place psychological strain on victims, for not only can they no longer access their vital information, they also know that if they don’t pay the ransom, the threat group may publish their most sensitive or confidential information on their twin leak sites.

It has become a relatively common practice of ransomware groups in recent years to “name and shame” victims in the hopes they can force them to pay out the ransom to decrypt their files and avoid their sensitive data being publicly released online. Damages from such an attack on a typical SMB can run the gauntlet from reputational brand damage, to the publication of privately held intellectual property (IP), leakage of confidential client or employee data, and the associated loss of public and shareholder trust in the targeted organization.

Figure 14: Lynx’s dark web leak site, showing their “wall of shame” of victims.

Targets

Figure 15: Lynx ransomware victim geolocation (mid-September 2024).

Figure 16: Number of Lynx victims per region (mid-September 2024).

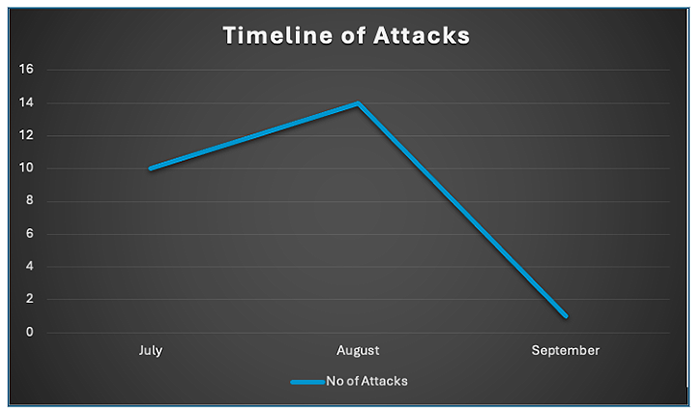

Figure 17: Timeline of Lynx attacks (Mid-September 2024).

Conclusions

Ransomware remains a constant scourge on the cybersecurity landscape and despite the efforts of law enforcement and defenders worldwide, continues to trend in the wrong direction. Driven by the promise of monitory gain whilst paying lip service to ethics, cybercriminal groups like Lynx continue to compromise, encrypt and exploit whilst profiteering off the damage and stress they’ve caused their victims.

In recent years, ransomware operators have become more organized, rapidly exploiting vulnerabilities in software systems and conducting opportunistic attacks on their victims. Though BlackBerry cannot currently comment directly on the tools, tactics and procedures (TTP’s) of the Lynx threat group, direct correlations with the INC Ransom group have been noted in our initial analysis, with clear overlaps in code-structure between the two group’s file-encryptors, the same email used in the registry information of the public Internet leak-sites of both groups, and the same shared pool of IPs.

Ultimately, ransomware remains one of the most lucrative and disruptive forms of cybercrime, and so long as organizations continue to pay their ransoms, groups like Lynx will continue to flourish.

Our Commitment to the Fight Against Ransomware

BlackBerry is committed to the fight against ransomware, and as such we are proud to stand alongside the 68 members of the International Counter Ransomware Initiative (CRI), which hosted its fourth Summit at The White House this month. As a global leader in cybersecurity, BlackBerry’s mission is to help protect governments, businesses, and safety-critical institutions of all sizes from cyber threats.

We are delighted to have been selected to co-chair the CRI’s new Public-Private Sector Advisory Panel, led by Public Safety Canada, which establishes a trusted set of private sector partners for CRI members to rely on when responding to ransomware attacks.

We look forward to collaborating with CRI members in combating ransomware by catalyzing effective information sharing, building trust through clear expectations and person to person collaboration, and developing best practices to navigate practical hurdles to combating ransomware.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs):

File

SHA256

|

Description

|

ecbfea3e7869166dd418f15387bc33ce46f2c72168f571071916b5054d7f6e49

|

Lynx Encryptor

|

571f5de9dd0d509ed7e5242b9b7473c2b2cbb36ba64d38b32122a0a337d6cf8b

|

Lynx Encryptor

|

eaa0e773eb593b0046452f420b6db8a47178c09e6db0fa68f6a2d42c3f48e3bc

|

Lynx Encryptor

|

Network

URL

|

Description

|

lynxblog[.]net

|

Surface Web Leak Site

|

lynxblogxstgzsarfyk2pvhdv45igghb4zmthnzmsipzeoduruz3xwqd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Leak Site

|

lynxblogco7r37jt7p5wrmfxzqze7ghxw6rihzkqc455qluacwotciyd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Leak Site Mirror

|

lynxblogijy4jfoblgix2klxmkbgee4leoeuge7qt4fpfkj4zbi2sjyd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Leak Site Mirror

|

lynxblogmx3rbiwg3rpj4nds25hjsnrwkpxt5gaznetfikz4gz2csyad[.]onion

|

Dark Web Leak Site Mirror

|

lynxblogoxllth4b46cfwlop5pfj4s7dyv37yuy7qn2ftan6gd72hsad[.]onion

|

Dark Web Leak Site Mirror

|

lynxblogtwatfsrwj3oatpejwxk5bngqcd5f7s26iskagfu7ouaomjad[.]onion

|

Dark Web Leak Site Mirror

|

lynxblogxutufossaeawlij3j3uikaloll5ko6grzhkwdclrjngrfoid[.]onion

|

Dark Web Leak Site Mirror

|

lynxchatly4zludmhmi75jrwhycnoqvkxb4prohxmyzf4euf5gjxroad[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site

|

lynxch2k5xi35j7hlbmwl7d6u2oz4vp2wqp6qkwol624cod3d6iqiyqd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site Mirror

|

lynxchatbykq2vycvyrtjqb3yuj4ze2wvdubzr2u6b632trwvdbsgmyd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site Mirror

|

lynxchatde4spv5x6xlwxf47jdo7wtwwgikdoeroxamphu3e7xx5doqd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site Mirror

|

lynxchatdy3tgcuijsqofhssopcepirjfq2f4pvb5qd4un4dhqyxswqd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site Mirror

|

lynxchatdykpoelffqlvcbtry6o7gxk3rs2aiagh7ddz5yfttd6quxqd[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site Mirror

|

lynxchatfw4rgsclp4567i4llkqjr2kltaumwwobxdik3qa2oorrknad[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site Mirror

|

lynxchatohmppv6au67lloc2vs6chy7nya7dsu2hhs55mcjxp2joglad[.]onion

|

Dark Web Chat Site Mirror

|

Other

Name

|

Description

|

.LYNX

|

File Extension

|

README.txt

|

Ransom Note

|

E:\\Lynx\\Release\\Lynx.pdb

|

PDB

|

Countermeasures

YARA Rules

import "pe"

import "math"

import "hash"

rule Malware_Ransomware_Lynx_INCRansom_2024 {

meta:

description = "Detects Lynx and recent iterations of INCRansom file-encryptors"

author = "The BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence Team"

last_modified = "2024-09-11"

created_from_sha256 = "eaa0e773eb593b0046452f420b6db8a47178c09e6db0fa68f6a2d42c3f48e3bc"

created_from_sha256 = "a5925db043e3142e31f21bc18549eb7df289d7c938d56dffe3f5905af11ab97a"

version = "1.0"

strings:

$s0 = "[+] Start encryption of directory: %s" fullword wide

$s1 = "[+] Sending note to printer: %s..." fullword wide

$s2 = "[+] Trying to open printer: %s..." fullword wide

$s3 = "[-] Failed to mount %s Error: %d" fullword wide

$s4 = "[+] Success! Closing printer: %s" fullword wide

$s5 = "[+] Start encryption of: %s" fullword wide

$s6 = "[%s] Encrypt network shares" fullword wide

$s7 = "[%s] Stop using process" fullword wide

$s8 = "[%s] Load hidden drives" fullword wide

$s9 = "[+] Found drive: %s" fullword wide

$s10 = "[+] Encrypting: %s" fullword wide

$s11 = "[+] Mounted %s" fullword wide

$s12 = "[%s] Debug" fullword wide

$s13 = "[*] Loading hidden drives..." fullword wide

$s14 = "Microsoft Print to PDF" fullword wide

$s15 = "\\background-image.jpg" fullword wide

$x0 = {8203E067292914706E0E0A850AB727FC2FD24638211B2E26C9265CFC6D2C4DED2AC45A130D3853DFB3959D54730A65DE63AF8BB

B0A6A76A8B2773C2EC9C281E6AEED47852C72923B358214A1E8BFA26403F14C4B661AA8013042BC708B4BC29197F8D0A3516CC730BE54061

9}

$x1 = {2F8A4222AE28D791443771CD65EF23CFFBC0B52F3B4DECA5DBB5E9BCDB89815BC2563938B548F3F111F15919D005B6A4823F929

B4F19AFD55E1CAB18816DDA98}

$x2 = {5B002B005D0020005300750063006300650073007300660075006C006C0079002000640065006C00650074006500200073006800610064006F

007700200063006F0070006900650073002000660072006F006D002000250063003A002F00}

$x3 = {38243828382C383038343838383C384038443848384C385038543858385C386038643868386C387038743878387C38}

$x4 = {35203528353035383540354835503558356035683570357835}

$x5 = {37203728373037383740374837503758376037683770377837}

$x6 = {09456E6372797074206E6574776F726B207368617265730A}

condition:

//Must be MZ File

uint16(0) == 0x5a4d and

//Exactly 5 Sections

pe.number_of_sections==5 and

//File smaller than 200KB

filesize < 200KB and

// Three Specfic Imports

pe.imports("CRYPT32.dll", "CryptStringToBinaryA") and

pe.imports("WINSPOOL.DRV", "WritePrinter") and

pe.imports("WINSPOOL.DRV", "StartDocPrinterW") and

//8 out-of 15 Strings

8 of ($s*)

//All-of Hex

and all of ($x*)

}

|

Related Reading:

About The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence Team

The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence team is a highly experienced threat research group specializing in a wide range of cybersecurity disciplines, conducting continuous threat hunting to provide comprehensive insights into emerging threats. We analyze and address various attack vectors, leveraging our deep expertise in the cyberthreat landscape to develop proactive strategies that safeguard against adversaries.

Whether it's identifying new vulnerabilities or staying ahead of sophisticated attack tactics, we are dedicated to securing your digital assets with cutting-edge research and innovative solutions.