.NET Stubs: Sowing the Seeds of Discord

Update 05.27.22: An unknown APT group is targeting Russian government entities with at least four separate spear-phishing campaigns since the beginning of the Ukraine conflict. Source: Security Affairs.

Earlier this year, as the rest of the world was just beginning to turn a concerned eye to unsettling military actions in Ukraine, the security industry’s attention was trained on malicious cyber activity in the country. When the WhisperGate wiper was discovered – a multi-staged malicious wiper disguised as ransomware – researchers dug in to see what we could learn about the techniques used by its authors, and what it could teach us about the threat landscape in general.

In this post, we’ll retrace our steps down a surprising rabbit hole that was revealed while examining this momentous malware. We’ll discuss what we found, and what it can tell us about the methods threat actors are finding useful to accomplish their nefarious actions.

Analysis of the WhisperGate malware wiper targeting Ukraine in early 2022 first shone a light on using a Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL) stub as a delivery mechanism for the malware, which was abusing the Discord content delivery network (CDN). When we investigated these stubs further and looked for others like them, we found them to be used in the delivery of a far larger array of commodity .NET-based malware.

Whispers in the Wind

We’ve covered details regarding WhisperGate in a previous blog, which provides a more extensive breakdown into the third and fourth stages of the wiper. What stood out to us, in the course of conducting that research into the final stages of the malware, was the MSIL stub used in the delivery of the third stage of the malware that was first noted by ESET Research.

To put it simply, these stubs are components of small Windows® executable files that act as downloaders for a subsequent main payload. The .NET framework includes individual compilers for various programming languages, such as VB.NET, and C#. An MSIL stub is created after the compilation of source code by these different .NET compilers, which can then be used across any environment.

This main payload that this stub delivers is typically commodity .NET malware, such as Agent Tesla, and QuasarRAT among others. While WhisperGate appeared to use the service that created this stub on only one occasion, we wanted to dive a little further into it and see why this method in particular is being used to deliver so many common .NET-based malware families.

Figure 1 – Code to resolve DownloadData function and download the payload

Dissecting the Stub

The WhisperGate stub itself is quite rudimentary; aside from a download function, it also sports junk strings, junk code, and other relatively simple attempts at obfuscation. The main work of a stub is done by retrieving the function DownloadData, or in some cases GetByteArrayAsync, using the .NET inbuilt function GetMethod to resolve the specified function call dynamically.

While this may not seem like a big deal, the name of the function to be resolved is often interspersed with a specific character, or set of characters, to obfuscate the function name. For example, a function like DownloadData would be obfuscated with character replacement such as DxownxloxadDxatxxax. Upon execution, this would be replaced inline to revert the function to its original form to perform its intended task.

Once the method has been resolved, it then downloads the file at the specified plaintext and hardcoded command-and-control (C2) URL. We observed evidence of the Discord CDN being abused heavily within our data set of files using this stub template, but occasionally saw other IPs and domains used as well.

Another interesting feature we noted is that the stub used by WhisperGate has been obfuscated with a tool called NetReactor, though it appears WhisperGate only used a small subset of the features that the NetReactor tool boasts.

We decided to test a version of NetReactor to see if the string obfuscation we observed with the resolved functions (as in the example above) was a feature of the packer. It was here that the rabbit hole got deeper. We found that string obfuscation was not a feature, which meant that a separately maintained tool or service was used to create these stubs.

Digging Into Discord CDN Abuse

Discord is a large communications platform that is widely used in gaming circles. It is comprised of topic-based channels where people can communicate over text, voice-chat, and video calls. They may even share files. These files are kept on Discord's CDN servers.

Threat actors can easily abuse the Discord CDN service to host their malware, which gives them the added benefit of blending in with typical, benign traffic on a network. This abuse has been documented as far back as October 2019, and it has been previously described by many other researchers, notably Sophos. With over 140 million monthly users at the time of writing this blog, and an easy-to-use file hosting and sharing mechanism, Discord has been an enticing prospect for abuse by threat actors.

An analysis by RiskIQ noted that a large portion of the stub payloads have links that were formatted as follows:

hxxps://cdn.discordapp[.]com/attachments/[Channel_ID]/[Attachment_ID]/[file-name]

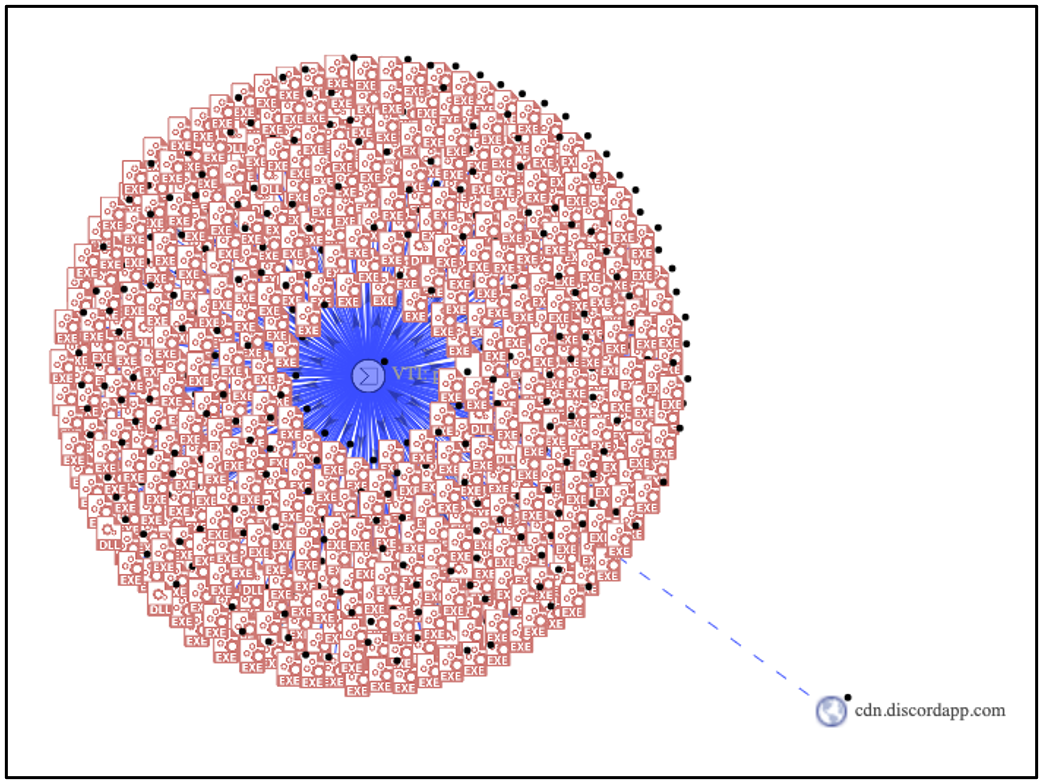

In fact, querying VirusTotal for any files that contain the domain "cdn.discordapp.com" and which have over 50+ positive hits for malware, returns a staggering 36,600 samples.

Figure 2 – VT graph showing files that contain cdn.discordapp and 50+ positives

PureCrypter

While the stubs can differ in their overall make-up, they all have defining features within the download function that bind them together in a way that identifies them as (most likely) having been made by the same service.

For example, the use of the DownloadData and GetByteArrayAsync functions, the manner in which they are resolved, and the particular style that’s used to obfuscate each function name, all point to their being created by the same service. This similarity also includes how frequently Discord is used as the delivery platform. Yet another lead presented itself when we saw the term “PureCrypter” referenced within one of the binaries gathered from our hunting efforts.

PureCrypter, as the name suggests, is a “crypting” service that can be found on the dark web, as well as in known hacking forums. In this context, crypting is the act of obfuscating or encrypting a binary through several means, to prevent detection by scanning solutions.

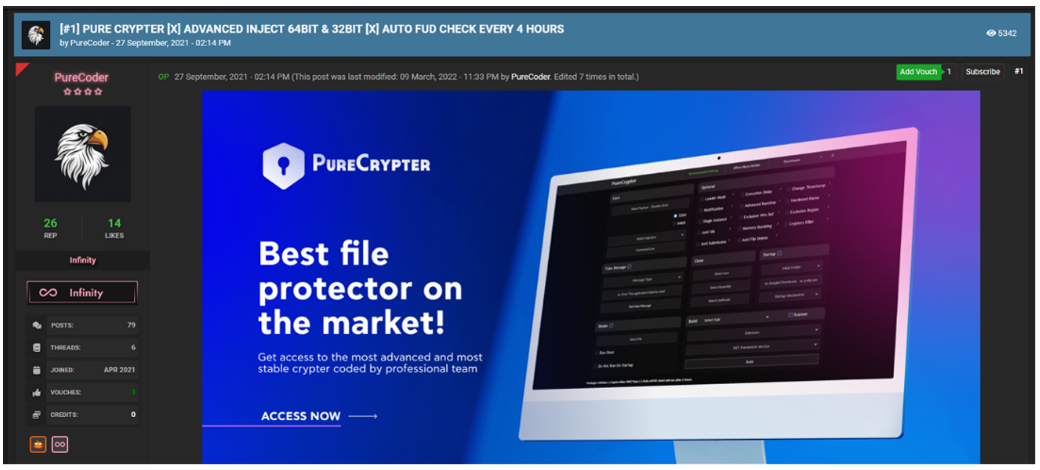

A term we often see in relation to these crypting services is “FUD,” which is short for “Fully Un-Detected.” PureCrypter advertises that they do a FUD check every four hours – meaning that they check their obfuscation against existing security solutions, to see whether they’re still “fully undetected” – in order to try keep ahead of defenders.

A hacking forum user that goes by alias of PureCoder has been advertising and actively promoting the PureCrypter solution since at least September of 2021.

Figure 3 – PureCrypter post by PureCoder

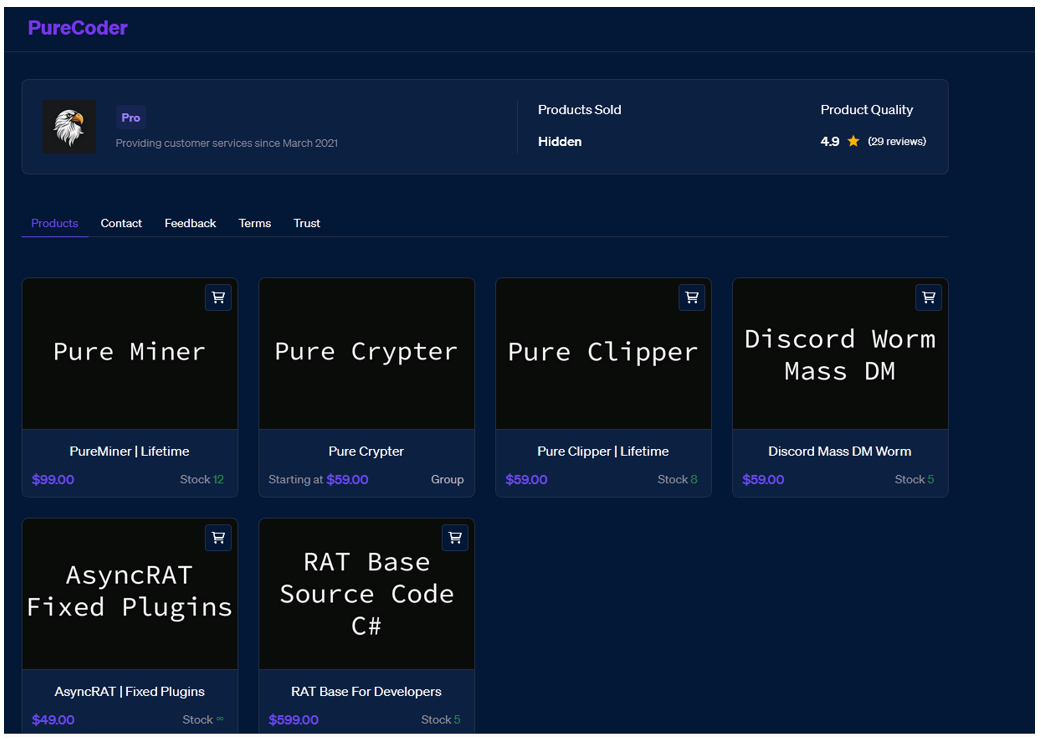

PureCrypter can be purchased on PureCoder’s website along with other illicit cyber-offerings such as:

- PureMiner – A silent miner that can be used either to spread itself, or other bots, to automatically mine Ethereum or Bitcoin into the malware operator’s wallet

- PureClipper – A silent and hidden clipper that detects and replaces a victim’s crypto addresses with those belonging to the malware operator

- Discord Worm Mass DM – Sends mass direct messages (DMs), and creates a payload.exe that is used for stealing tokens

- AsyncRAT fixed plugin – Fixes errors in AsyncRAT plugins

- RAT Base Source code C# – C# source code for those that are working with RATs (remote access Trojans). It offers FUD and claims to have a clean detection rate at 0/26 antivirus (AV) products identifying it as malware. It also boasts a small binary size at 176KB, and it claims to be better than any other RAT available on GitHub, due to its clean detection rate.

Figure 4 – PureCoder’s website

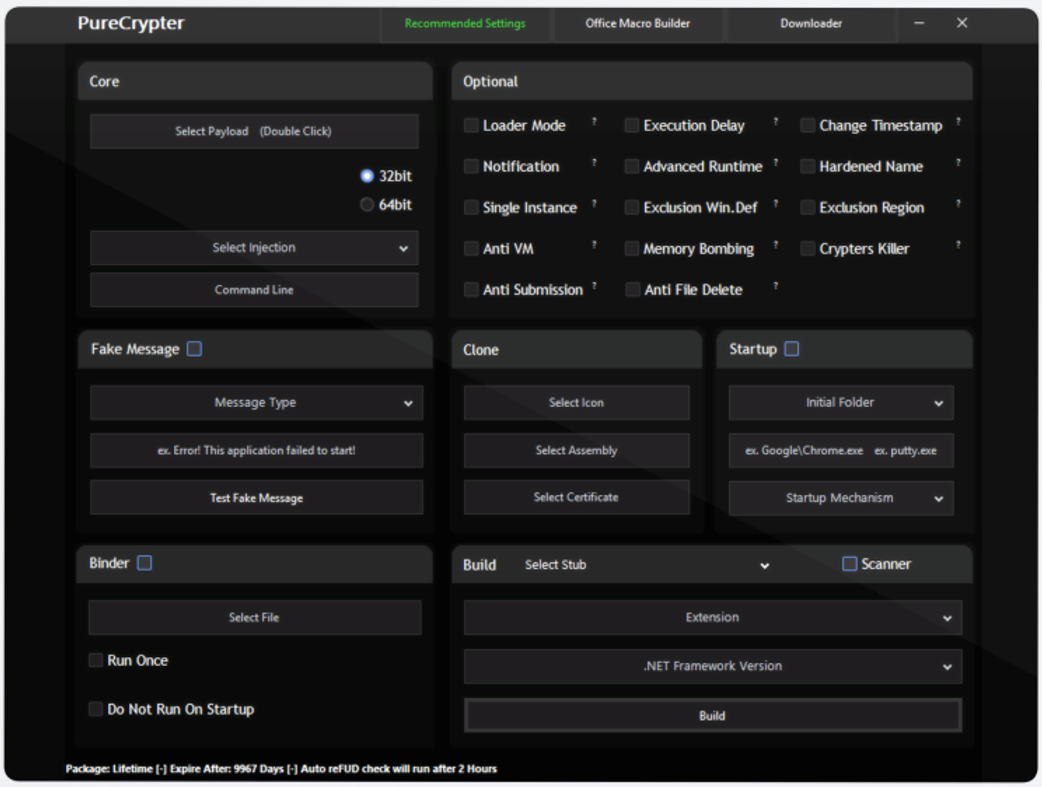

The PureCrypter solution offers three different purchase options. The tool features offered are the same for all three; the only difference is in the length of time the tool is available for the purchaser to use it, as illustrated in Table 1. The threat actors accept payment in Bitcoin, Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash, or Monero.

| $59.00 | 30 days |

$109.00 | 90 days |

$245.00 | Lifetime |

| Stub daily updated |

| .NET and Native support |

| Inject 32bit and 64bit |

Command line

|

| Time-stamp |

| Exclusion region |

| Hardened name |

| Crypter killer |

| Memory bombing |

| Anti-file delete |

| Anti-sample submission |

| Discord and Telegram execution notification |

| Icon, assembly, and certificate cloner |

| Advanced injection |

| Fake message box |

| Three startup techniques |

| Scanner |

| Binder |

| Delay |

| Free Macro excel builder and downloader |

Table 1 – PureCrypter features

PureCrypter boasts several additional features such as binary obfuscation, Microsoft® Excel® macro builders, and downloader stub creation (sound familiar?). While we won’t cover everything that the program is capable of, some of the options that can be set at runtime can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – PureCrypter user interface

So far, we have a dataset of related samples, and we have a dark web crypter. The question is, how do they relate? We found the answer by identifying a command line argument, and seeing metadata of the samples at scale.

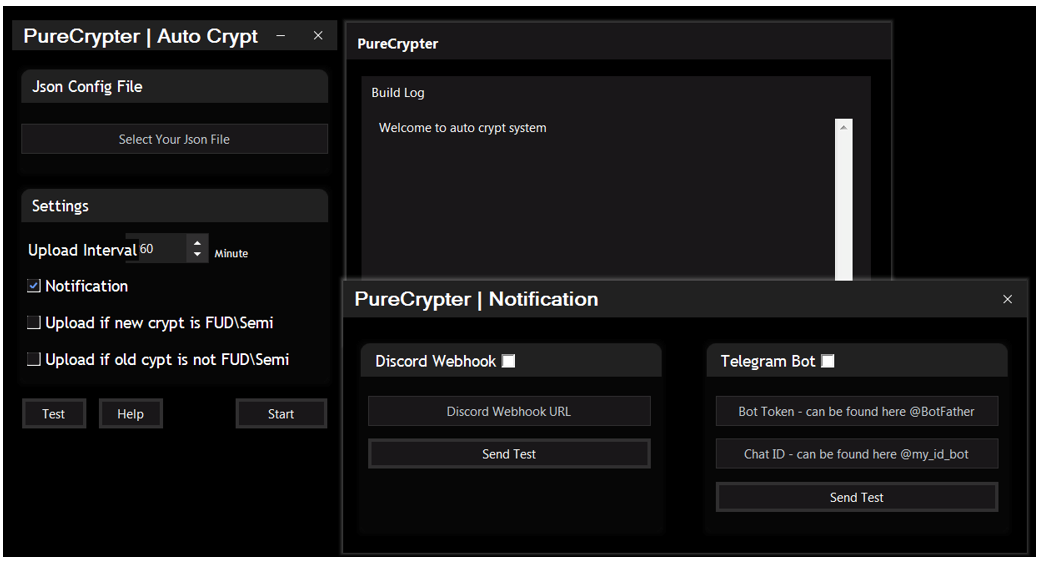

Figure 6 – PureCrypter with the ”autocrypt“ parameter

PureCrypter has additional functionality that can be seen when you run the tool with the “autocrypt” parameter. Figure 6 shows a “Notification” pane to which execution and infection notifications can be sent, either by a Discord webhook or Telegram bot notification.

When we take a topological view of the features we have discussed so far, and apply them to our dataset of similar stub files, we can see several places where they overlap:

- In addition to the payload download, multiple stubs contacted Telegram Bot API URLs.

- In addition to the payload download, multiple stubs contacted Discord webhooks.

- Multiple stubs had Excel macro execution as a delivery mechanism.

We can say with a high degree of confidence that the stubs in our sample set were created via PureCrypter.

Now that we’ve ascertained the origin of the stubs, let’s look at the variety of malware that uses PureCrypter’s services.

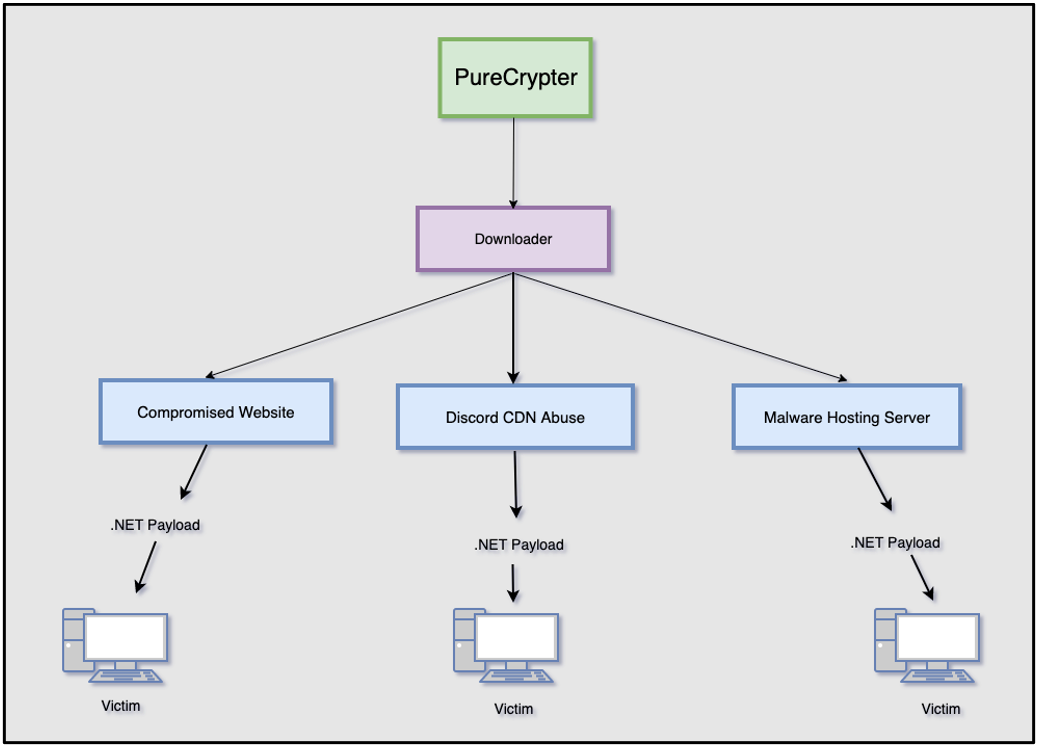

Figure 7 provides a high-level overview of the varying execution chains seen within the stubs we found in our dataset. Each one starts with a likely PureCrypter-generated download stub, which is then typically designed to retrieve a .NET malware payload from one of three locations: a compromised website, a malicious Discord CDN link, or a malware hosting server that was specifically set up for this purpose.

Figure 7 – Malware delivery execution chain

The Who’s Who of .NET Malware

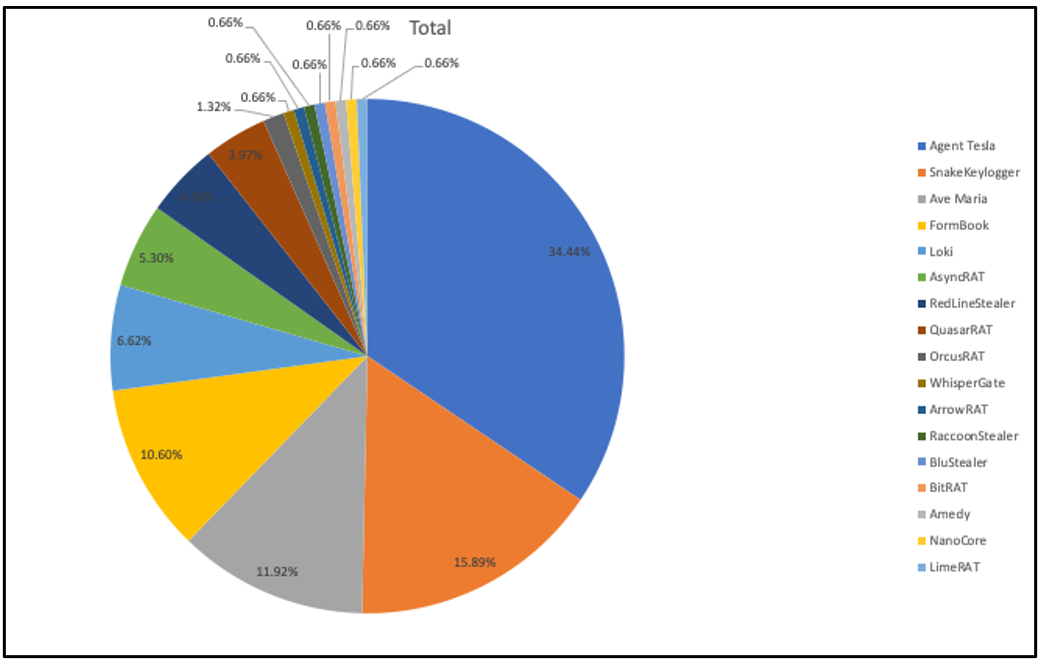

Being a C#/.NET/MSIL stub, the malware that is downloaded as the latter stage of a malware likely generated with PureCrypter is also C#/.NET. The following graphic displays a breakdown of the various malware families that were seen to be delivered as the final stage payload during our investigation.

As shown in Figure 8, Agent Tesla made up the largest portion of our sample set, at 34.44%. The second most prevalent family was Snake Keylogger, at 15.89%, closely followed by Ave Maria, at 11.92%. While the samples we have aren’t categorical, it’s certainly interesting to note which families have appeared most in our hunting.

Figure 8 – Samples of malware families likely using PureCrypter, breakdown by percent

Timeline of Use

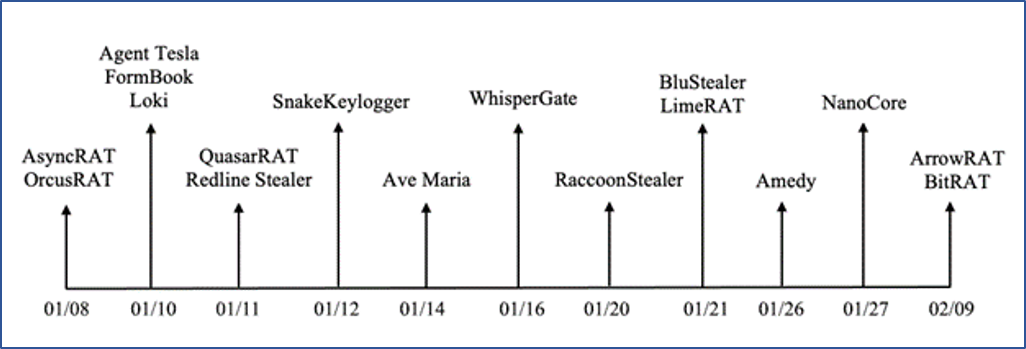

The diagram in Figure 9 displays a loose timeline of when each malware family appeared in the wild in 2022.

Figure 9 – Timeline of each malware family first seen in the wild in 2022

Conclusions

January 2022 was significant on the threat landscape due to the appearance of the malware wiper dubbed WhisperGate. This made headlines because of its targeting Ukraine’s private sector and government agencies.

As we analyzed WhisperGate samples, we were led to the unique MSIL stub that was used as the delivery mechanism to download the next stage payload. Using open-source intelligence techniques combined with some threat hunting, we were able to obtain additional files and attribute them to specific campaigns by various other threat actors.

During this investigation we kept wondering how these downloader files were created. Surely, there was some sort of "as-a-Service" tool being used, perhaps offered on the dark web. We were able to get more specific in our findings when we identified references to the term "PureCrypter" in our dataset.

Upon further investigation of PureCrypter, we found that it offered a variety of features that aligned with what we have seen thus far. If threat actors are using this crypter to achieve their nefarious goals, it means that this tool is doing exactly what they expected. By shining a light on this tool and associated campaigns, as an industry together, we have uncovered what they tried to hide.

About The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence Team

The BlackBerry Research and Intelligence team is a highly experienced threat research group specializing in a wide range of cybersecurity disciplines, conducting continuous threat hunting to provide comprehensive insights into emerging threats. We analyze and address various attack vectors, leveraging our deep expertise in the cyberthreat landscape to develop proactive strategies that safeguard against adversaries.

Whether it's identifying new vulnerabilities or staying ahead of sophisticated attack tactics, we are dedicated to securing your digital assets with cutting-edge research and innovative solutions.